Close to the Edge (13 page)

Authors: Sujatha Fernandes

Double Door was in the bohemian, gentrifying northwestern neighborhood of Wicker Park. There was a concentration of clubs in this area and farther north as well, in the whiter neighborhoods. Hip hoppers from the South Side and West Side had to come north to access the club scene. In earlier periods like the 1940s and 1950s, black entrepreneurs and blues and jazz musicians had propelled a vibrant entertainment circuit of cafes, nightclubs, and musical theater on Chicago's South Side and West Side. But with the economic crisis spurred by deindustrialization, most of these entertainment venues were shut down, with the exception of a few blues clubs that still attracted tourists.

On the North Side, hip hoppers had to struggle for spaces and venues. During a dry spell in the mid-1980s, they used to b-boy in the House clubs to keep their form alive.

10

Rap promoters faced stigma and hostility from white managers at the upscale North Side venues who associated rap music with crime, violence, and gangs. Other venues just didn't see revenue coming from the young and financially challenged hip hop audiences. “Hip hop nights” had become one means for Chicago hip hoppers to gather and perform. The first open mic night was organized by Duro Wicks at the Lizard Lounge in the Ukranian Village in 1991.

11

It was known as the one-dollar Sunday hip hop show. After that ended (as Wicks said in an interview, “It was just too black for the club and they let us go”), promoters and DJs began to host hip hop nights at other venues like Lower Links, Elbo Room, Double Door, and Subterranean. The hip hop night at Double Doorâdubbed the “Bluegroove Lounge”âwas started by the DJ Jesse De La Pena at the Elbo Room in 1994 and cohosted by Spo and Dirty MF. The DJs Pumpin' Pete, aka Supacuts, 33 1/3, and Nonstop would also spin at Double Door on hip hop night.

I caught up with Jesse sometime later, and he told me his story. Of mixed Irish, German, and Mexican descent, Jesse was raised on Chicago's Southeast Side by his single mother. When he was a teenager, they moved to the Southwest Side. He was into graffiti and break dancing and had a few friends who were DJs. He watched them and listened to their tapes, and then decided that he wanted to be a DJ. Since hip hop was not big at that time, an older DJ friend would pass along all his hip hop promo records to Jesse. Jesse listened to WHPK and other college radio stationsâwhich were the only ones at the time playing hip hopâand then he would buy the music he heard on the radio.

In high school Jesse saved up and bought a Technics 1200 turntable from a friend. He also had an all-in-one stereo player with a turntable on the top, so he started figuring out how to DJ using the knobs. He would turn the volume up and down like a fader on a mixer. He made a scratch pad out of an old album cover. Then, as he improved his skills, he got a mixer and eventually a second turntable. It was also a Technics 1200, pretty beat-up. The tone arm was cracked and Krazy-Glued back together; when it periodically fell off, Jesse reattached it with rubber bands.

As a DJ, Jesse had nowhere to spin hip hop. He lost a lot of early gigs playing hip hop. He relates that “when I started to spin it, everybody, including black folk, would leave the floor. Nobody was feeling it.” So he started out playing House, new wave, and industrial music at parties in clubs, basements, and warehouses for half-hour sets.

“At that point there were occasional hip hop events or concerts,” Jesse recalled. “I remember going to the Fresh Fest at the UIC pavilion [University of Chicago, Illinois] in 1985 or â86. It featured Whodini, Grandmaster Flash, and a bunch of other hip hop groups. I also saw Run-DMC and the Beastie Boys in concert. There were hip hop parties like Steps up north or the Blue Gargoyle on the South Side, but they all came and went, they never really lasted. So I was looking for somewhere that me and all my friendsâwho were DJs and b-boys and graffiti artistsâcould showcase our talents. The idea of doing a weekly hip hop night was really just a networking and a community thing. We started off at the Elbo Room, and then as it grew we needed a bigger location. Double Door just seemed to make sense because of its size and locationâbigger stage, better sound system. We just outgrew the Elbo Room.”

We entered the main floor of the club. There were a few scattered tables, with a large open area and a stage. The audience was mostly urban black youthâa mixture of aspiring rappers and b-boys up from the South Side and West Side, and some college students. This demographic would change dramatically in years to come, when the underground audiences would become largely white. Along one side of the club was a narrow fluorescent bar. But most of the crowd was focused on the cypher that had opened in the center of the floor. One after another, b-boys entered the ring. They warmed up with a few quick circular steps. Then they dropped to the floor and executed head spins, legs and arms whipping through the air, then balanced precariously in a freeze, while the crowd cheered them on. After a while a second cypher opened up, and people migrated over to see if they were missing anything there.

Jesse spun old-school records for a while, original soul, jazz, and rock, followed by an open mic. It was a trial by fire from a tough crowd that knew what it liked and what it didn't. The open mic scene pushed Chicago rappers to hone their skills and their stage presence. They weren't just studio rappers; they could work a crowd.

12

There was a certain buzz in the air because some big underground acts would make an appearance in the show tonight.

“Let's see some crowd participation,” the rapper Capital D of All Natural primed the audience, and a few people shouted back. “Do we keep it hard core?” he asked. “Hell, yeah,” the audience responded.

“Underground, straight raw, do the heads want more?”

“Hell, yeah!” the audience screamed.

“Do the heads want more?”

“HELL, YEAH!”

Over a minimal beat, with recorded scratching from DJ Tone B Nimble, Capital D rapped in a low voice,

Take it back to the days before b-boys was gettin' blown away

And sons was livin' off the props of their pops like Nona Gaye

13

But the pendulum will sway, and you're gonna pay

Will I be bopping to the beats that Tone'll play?

It's the only way, of course some will say that that's the lonely way

But hey, I'd rather stand on my own

Than be a puppet with a string on a microphone.

Then the riff, an underground anthem: “Now do we keep it hard core? / Underground, straight, raw / On tour, we're going from shore to shore, now do you heads want more? / Yo, do we keep it hard core?”

After All Natural, Mass Hysteria was on the stage. Over the speakers, there was a heavy bass with a high-pitched buzzing, like a swarm of insects or police sirens on alert. Treese was rapping over the top:

No one made you do this,

Would you stay true to this, if you weren't paid to do this

So stop bragging about your number one hit

I thought you knew, my crew don't care about that dumb shit.

I'm not one of you, not like you, none of you, not even some of you

Dis me, what will become of you, you'll be gone, for good.

My life don't mean shit to me, tell me why the fuck you think yours would.

Then more scratching and the hook to the song: “On the mike, I let vocabulary spill,” repeated over and over.

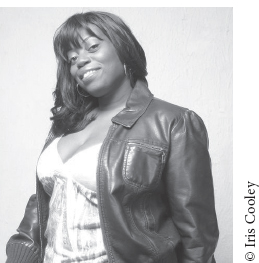

I was gratified to see a woman up nextâAngela Zone, aka Ang 13. Underground hip hop in Chicago tended to be a male affair. Ang 13's background beat, by the veteran Chi-town hip hop producers the Molemen, opened with the tones of a piano and synthesized violins. “I'll take you back in time, the year is â89,” 13 opened her rhyme, a personal narrative about her troubled relationship with her parents. “It was moms who brung this / Sit back, I'm gonna tell ya how my peeps and I swung it.” The song recounts 13's trips to the emergency room as a young child, her dad off with another woman, then her mom in jail while Ang 13 and her sister were raised by relatives.

“Moms had a lot of male friends who I detested,” 13 continued, “running in and out, then one night I got molested / Never talked to me about the incident as if it never happened / All I heard was her in the next room / It never got better, worst came to worst / Before she looked out for her kids, she always looked out for her man first.” On the chorus she rhymed, “You understand what it's like now / I hate their ways, yet I love 'em / Never will forgive my moms, she put my sister out at 18 / But first she tried to break her fuckin' arm / So many times I wanted to flex / But I knew I had to watch my neck, 'cause I knew that my ass would be next.”

Ang 13

Finally, as an adult, 13 reconciles with her mom. “'I'm sorry, forgive me / I love you, I never meant to snub you,' said moms / Said how she was dead wrong /

Sad songs say so much

, don't know how she hurt me so much / Situation made me go nuts.” These personal and raw narratives of women's experiences were something that was absent in corporate rapâbut they were also surprisingly rare in underground rap. It was also unusual to see women up at the open mic. Given underground rappers' polemic against the one-dimensional “bitches, hoes, and bling bling” formula, I thought that this scene would create more spaces for women, queers, and those generally outside the orbit of commercial rap. Why didn't that seem to be the case?

The final act for the night was the renowned freestyle battle rapper Che Smith, aka Rhymefest. Fest hailed from the far South Side neighborhood of South Deering and had come to fame the previous year, when at seventeen he and his rapping partner, Terrence Parker, aka MC Juice, had beaten the notable white rapper Eminem in an emcee battle at the Scribble Jam.

The track consisted of synthesized horns and bells leading into a sparse beat. “Well, hey, yo,” rapped Fest, over the top of the beat. He looked over to Juice. “What's up, Juice, it's about time that we set it straight and show these other cities how to represent and regulate / Y'all niggas don't want to spark me / I can hit the rhythm 'n' split 'em just from the drums of my heart beat / Yo, I can't deny I live and die for the streets of Chi / But there's more than meets the eye, than pimpin' hoes and getting' high / You do or die, but you can live and do the same thing.”

Juice entered, “No pause or comma, âcause I'm gonna keep you fearin' this / You got a question mark, I'm the nigga here, period.”

“Dope it is.”

“I am.”

“But can you rock?”

“I can.”

“You think ya dope.”

“I do.”

“That's how we chill, part two.”

Juice continued:

Versace wearing rappers, always tryna play some pimps in this biz,

These record labels sign the most unpresentable

Hits that go platinum for grabbin' on their genitals

And every single day brothas is dyin' in my mix,

But all they ever rap about is Alize and grabbin' dicks.

Now you might say who is Juice to try to check sombody else,

But it do get kinda boring always rappin' âbout yourself

And your jewelry and your guns, you think that shit is rhymin'?

The billboards say you climbin' but every trend has its timing

I ain't sayin' no names, but why you bitin' his style

I'll have all you niggas layin' in the casket with your Cristal

There was a certain reality to underground rappers' beef with corporate capitalism. It wasn't theoretical, as in the case of the Cuban rappers who experienced capitalism by long distance. It came from years of winning Scribble Jam battles and still working low-wage jobs or from seeing countless young black men in the âhood hoping to get rich and dying trying. If underground rappers sounded bitter and cynical, it came from seeing the meteoric rise of those willing to embrace the music industry formulas, while their years of “paying dues” by studying and nurturing the culture with scarce resources counted for naught in the marketplace of MTV.

I

t was a Tuesday night at Subterranean, and a sizable crowd had gathered to see Chicago's finest hip hop DJs. The attention of the audience was focused on Johnny Cervantes, aka DJ Presyce, who had worked with Mass Hysteria and had been a part of crews the Molemen and Turntable Technicians. DJ Presyce was a round-faced Mexican American guy who grew up on the South Side at Sixty-third and California. When he was fourteen, Presyce and his older brother Jesus, or “Chuy,” watched tapes from the annual DJ competition known as the DMC World DJ Championships, and they taught themselves how to scratch. Chuy was a car mechanic, and he and Presyce mastered the inner machinery of their turntables by taking them apart and then putting them back together.

Presyce won the DJ battle at the Cincinnati-based Scribble Jam contest three years in a row before being forced to retire from the competition. In 1998 he participated in a regional DMC DJ battle, winning a spot in the US finals, where he came in second in 2002. But being a dope battle DJ didn't really translate into money, and Presyce was working at Best Buy and Target to get by.

The earnest audience at Subterraneanâconsisting of mostly male DJs, emcees, and fansâfilled the cocktail tables at the front and center of the room. People were focused intently on the turntables, appraising every move of the DJ. Others were drinking and talking quietly on the sides and at the back of the club on velvet couches. It was very different from a typical club scene, where people got drunk, flirted with each other, and shouted over the din of the music. Here all attention was on the DJ at the front.