Close to the Edge (22 page)

Authors: Sujatha Fernandes

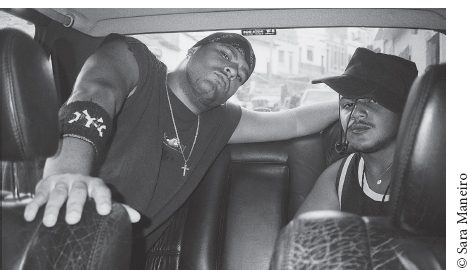

In person Pedro Pérez, aka Budu, of Vagos y Maleantes was a sweet, brown-skinned, round-faced young man. Nothing like his album cover image of a traditional gangster packing a 9mm handgun. Carlos Madera was a tall, lean guy with a thin moustache. Madera's stage name, El Nigga, was borrowed from American gangsta rap vernacular, where the term has been pervasive and often controversial. Robin Kelley says that gangsta rappers' spelling of the word as

nigga

, rather than the the derogatory

nigger

, points to a new collective identity shaped by class, police repression, and poverty.

9

That might suggest why it resonated with barrio youth. Budu and El Nigga had grown up in Calle Carabobo of the barrio San Jose de Cotiza, known ominously as

la boca del lobo

, or the mouth of the wolf. They listened to Ice-T, Afrika Bambaataa, Run-DMC, and Snoop Dogg, and while they enjoyed the music and the rhythms, they didn't understand any of the words. The lyrical content of rap music traveled to them via Puerto Rico, and rappers such as Vico C, who rapped in Spanish. Vagos y Maleantes was also heavily influenced by

salsa brava

, a bass-heavy, jazz-inspired form of salsa, popularized by groups in the 1970s and 1980s, such as Hector Lavoe, Eddie Palmieri, and the Fania All Stars.

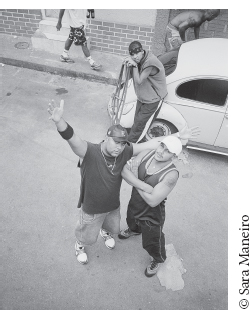

Budu and Nigga of Vagos y Maleantes. Cotiza, Caracas, 2003

Budu and Nigga of Vagos y Maleantes. Cotiza, Caracas, 2003

Budu first became involved in hip hop through b-boy culture, which arrived in Venezuela in the early â80s. He belonged to a crew and would spend all his time at b-boy battles in the towers of Parque Central and in Sabana Grande. The next phase to come along was hip hop videos and rap. “The first group that I bought in vinyl was Run-DMC,” said Budu. “They were the first ones to impact me with their song âWalk This Way,' with Aerosmith.” As Budu was talking, I thought back to my own first music cassette in Australiaâ

Hits of Summer

87âand how the same Run-DMC song had grabbed my attention as a teenager.

“The moment arrived where I thought that hip hop culture would be implanted here in Venezuela. Then it disappeared in the nineties, I don't know what happened,” explained Budu. “But hip hop culture always remained with me,” he continued. “I would buy the discs, dance in my house, and I always had the faith that this movement would return. I continued in the streets, in my own thing, but I always listened to hip hop music, as well as salsa, jazz, and funk. El Nigga was a poet. His father was in the mafia, and I remember there'd be gatherings of those mafia types. They called El Nigga to do his poetry for his father's friends, all of them drunk. One day we saw these

panas

[friends] from the group El Corte, and we liked the way the audience moved, the presence of the rapper, the music, and we realized that we liked it. He and I began to write. We began to make music and we began to record.

“One day we got a call from DJ Trece. He invited us to his studio to record a song. We went, and I think we were the first group here in Venezuela to do gangsta rapâtalking about the doctrine of the streets, something that had a strong impact in the Caracas underground and in all of Venezuela. The song had an impact. We thought we'd be able to record a disc, but, no, it was all for nothing. The disc didn't come out. Trece fought with his manager. The group dissolved, and the disc was not produced. So we went back to the bottom, to the streets again.

“We were thinking, there's no one who'll support us, nobody can pay for a studio for us. Well, let's sell drugs to pay for our own production. So we took turns standing on the street corner below. They'd say, âHey, deliver this for me,' and so on. And in this way we recorded six songs, paying for them ourselves, until the day that Juan Carlos Echeandia came with his proposal of a documentary,

Venezuela subterráanea.

He must have been sent by God. We were practically ready to go into jail, because the police would see me, recognize me, and they'd say, âWe're going to take you, we're tired of this.' They had shut down my bodega. I had a business and they shut me down.”

Vagos y Maleantes, as Budu and Nigga called themselves, was a play on a 1956 law known as Ley sobre vagos y maleantes (Law for vagrants and criminals). The law was devised during the military regime of Pérez Jiménez in order to imprison dissidents and later those considered undesirables by the authorities. But in reality Budu and Nigga didn't want the life of vagrants and criminals. They wanted the stability of work and family that was always out of reach. “In the barrios there's a lot of violence, every day more violence,” said Budu. “But what we want is to end delinquency. What we want is more sources of work. What we want is for our children to have an education.”

A

fter hearing DJ Trece mentioned several times, I was curious to meet him. I barraged Duque with questions. What was Trece's background? How did he get started? Where did he get the equipment to produce beats? Duque just shrugged his shoulders in response.

Juan Carlos arranged for Duque and me to appear on DJ Trece's weekly hip hop radio show. We took the elevator up to the tenth floor of the Ateneo de Caracas, an arts center close to downtown. The doors opened onto a small lobby where some rappers were sitting on a couch. Outside speakers carried the perky voice of the R&B singer Kelis: “My milkshake brings all the boys to the yard / And their life, it's better than yours. Damn right, it's better than yours.”

We could see DJ Trece speaking into a microphone in a studio inside. He was a tall white guy with longish brown hair. He lined up another song, and then his assistant ushered us in. Trece rose, shook hands with us, and spoke in English, “Hey, yo, what's up?” Duque rolled his eyes at me; he didn't understand any English.

As we settled into the seats, Trece continued addressing us in English. It seemed that Trece was trying to upstage Duque in front of the foreigner, show him to be just another guy from the barrio, while Trece flaunted his international credentials. I tried to steer the conversation back to Spanish, so that Duque wouldn't feel left out. But Trece was determined to speak in English.

Trece proudly told me that he was born in New York, while his mother was doing a PhD at New York University, and he grew up in Greenwich Village. He studied visual arts at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, later transferring to the San Francisco Art Institute. After graduating from college, he became involved in hip hop culture and moved to Mexico to become a DJ. In Mexico he learned how to make beats, then returned to Venezuela to become a producer. He began working with Guerrilla Seca and Vagos y Maleantes. “These guys coming from the streets were

malandros

,” he said. “They wanted to be an artist like me, but they grew up in a different environment that wasn't so artistic.”

“In ninety-seven, when I came back to Venezuela,” Trece continued, “people didn't even know the word

DJ

or

hip hop.

I was the only DJ in this era. So through the radio I decided to make my own network. The movement of hip hop began to grow and evolve and awaken the barrios. I was a catalyst. I acted as a jump-start for the movement to begin. That is, I'm the one responsible for hip hop in Venezuela.

Y al mismo tiempo

he said, slipping back into Spanglish, “I found in hip hop the right brush for my art. It wasn't oil painting or sculpture making or photography. It was hip hop.”

I could now see the reason for Duque's earlier evasiveness about Trece. It was not just that Trece was egotistical, but his account of hip hop's development in Venezuela seemed typical of

many origin narratives of global hip hop, in that it excluded the people who had been part of the first waves of hip hop culture, who had participated as b-boys and rappers from the very beginning. It was another way of making people like Duque and Budu invisible, and of giving all credit to the people who brokered hip hop's entrance into the mainstream. But, while hip hop was a personal project for Juan Carlos, or an artistic medium for Trece, for the rappers in the barrios the music was much more than thatâit was what they lived.

“If hip hop started as a black and Latino movement,” continued Treceâat least he acknowledged that much (for all of his professed education, Trece seemed remarkably ignorant of the African American history and culture that gave rise to his “paintbrush”)â”now it's amazing that there are no limitations, and that is my first line, no limitations. And there are people who can prove that. You see it with Eminem and DJ Shadow, for example, one of the biggest beat-making scientists there is. And he is a white kid from the suburbs. And Elvis Presley, for instance, how he translated black music. Eminem is like an Elvis Presley. No limitations and anything is possible, anything goes. If you want to rap about bling bling, that's cool. If you want to rap about politics, that's cool. If you want to rap about sex, that's cool. It doesn't bother me.”

The song Trece was playing was coming to an end, and he reached for another CDâVagos y Maleantes'

Papidandeando.

He positioned the CD to a track he had produced, “Historia nuestra” (Our history), and he hit

play.

Suddenly, the room vibrated with the brassy tones of a buoyant salsa beat. Then Budu's voice rapping:

From a kid, I was raised in the barrio, or in other words, hell

Where nobody is immortal

Get comfortable and listen to the biography of these two guys

â¦

My mama works hard without rest

My father abandoned me when I was a kid

I don't care âcause I don't need him

At seventeen, I got sick for money, and I started to deal drugs

A different environment, other life

Now people see me like a real delinquentâ¦

The problems were abundant in my nuclear family

They dreamed of me being an engineer, and I dreamed of being a criminal

There was something jarring about Trece's upbeat salsa music and Budu's dark lyrics. They didn't seem to fit together. I thought back to all the other producers I knewâPablo, Munkimuk, Khaled, DJ Presyceâall people who came from the same marginal communities as the rappers they produced, and whose beats allowed the lyrics to speak in all their pain and poetry. But in Venezuelan hip hop, where commerce and privilege met the harsh realities of the streets, the dissonance of the music was itself an expression of the unbridgeable divide that existed out there in the city.

T

he central district of Caracas was covered in a haze of black smoke. On the Avenida Baralt a vehicle of the Metropolitana was going up in bright orange flames, its molten core giving way to gray and black plumes of smoke that filled the atmosphere and choked our lungs. All the way down the street and in side alleys, people burned motorcycles belonging to the Metropolitana. They set fire to advertisements for Polar beerâa company owned by the billionaire Gustavo Cisneros, who had helped to finance the 2002 coup against Chavez. Bystanders watched, some chanted slogans, and the police looked on from the distant fringes, afraid or unwilling to intervene.

The palpable anger arose from an announcement that day, June 3, by the National Electoral Council (CNE) that the opposition had gathered the 2.4 million signatures needed to trigger a referendum on whether to recall Chávez from power. The referendum was scheduled for August 15. But just a few months earlier the CNE had ruled that one-third of the signatures presented by the opposition were not valid. The CNE had made the lists public and gave the opposition five days in May to validate the signatures. Barrio folks who supported Chávez were appalled to find that the opposition had fraudulently used their names or had used the names of their long-dead parent or uncle. Yet despite efforts of people to purge these names, the CNE ruled that the opposition had gathered sufficient signatures and the referendum would go ahead. It was a slap in the face for an underclass that had been swindled by powerful groups one time too many. As I stood watching the streets go up in flames, I received a text message from Johnny:

“Camarada, nos jodieron”

(Comrade, they screwed us).