Close to the Edge (23 page)

Authors: Sujatha Fernandes

D

uring June and July barrio folks accepted the hard reality that the recall referendum would go ahead. They set about organizing a “Vote NO” campaign in the streets and in the barrios that would ensure a massive turnout of Chávez supporters to vote against recall. The shantytowns were the site of fervent preparations as residents set up voter registration centers, organized colorful marches and parades, and went door to door to enlist support. The cultural establishmentânow nominally Chavistaâalso joined in the efforts. On August 6 the cultural establishment organized a rap concert in the Poliedro stadium, billed as the First International Festival of Youth Music. The slogan was “Say NO to Drugs”âa thinly veiled attempt to incorporate the Chavista referendum slogan.

I arrived at the Poliedro with Duque, Yajaira, and Mike Walsh from Chicagoâwho was now my husband and was visiting me in Caracas. The three-thousand-capacity stadium was almost filled. The audience was mostly young people from the barriosâbrown and black skinned, clad in hip hop gear. Outside there were vendors selling cans of beer. The alcohol fueled a heady mixture of masculine aggression and youthful energy as the young men jostled one another in the vast open floor space in front of the stage that was known as the

parte baja.

We took our seats in the rear mezzanine, overlooking the scene.

An hour passed with no signs of any bands coming onto the stage. Young people in the

parte baja

were starting to get drunk. Periodically, they would propel half-empty beer cans across the room. From the upper levels it was a spectacle to see hundreds of beer cans rocketing around the

parte baja

, the yeasty odor of spilled beer combining with the sweaty stench of crowded bodies.

Finally, the first group for the night began setting up. They were a rock group from Colombia. As these white boys with guitars and long hair began a mellow ballad, the audience was restless. The

rockeros

began a second song, a more upbeat rock song. The young people in the audience started to become agi-tated. Halfway through the song they shouted at the performers,

“Fuera, fuera”

(Get off, get off), and threw beer cans and other debris at the musicians. The guitarists stopped playing and castigated the audience: “You are a bunch of uneducated kids. You have no respect.”

Yajaira, Duque, and I looked incredulously at each other. How could the organizers have enlisted a white rock band to play before this crowd of barrio youth? While rock music was popular among middle-class kids, in the macho culture of barrio youth it was derided as

guachu-guachu

, rejected as sissy or effeminate. As Duque put it in his liner notes for the

Venezuela subterránea

disc, “In the '70s, a

malandro

who listened to the Bee Gees was like a 45-caliber handgun covered in Hello Kitty stickers.” In the barrios it was the

tambores

, the infectious rhythms of salsa, and now rap and reggaeton, that were popular.

Things went from bad to worse. More white rock groups from Colombia and Argentina were booed off the stage. Each group took a long time to set up. There were sound and technical problems. Tension and frustration mounted in the

parte baja

, as the youth consumed more beer, and fights began to break out.

Then one of the organizersâNoel Marquez from the Afro-Venezuelan drumming group Grupo Maderaâcame onto the stage. Grupo Madera members were strong supporters, even spokespersons, for the Chávez government; their hit song “Uh ah Chávez no se va” (Uh ah Chávez won't go) was the anthem of the Chavista movement.

“Who is Chavista here?” shouted Marquez. There was a feeble response. “Who is Bolivariano here?” A scattering of people raised their hands. Marquez left the stage, satisfied that he had placated the crowd while the sound engineers worked to fix some technical problems. But as time went on, the young people grew more impatient. Marquez kept reappearing on the stage, yelling, “Who is Bolivariano?” “Who will vote NO?” People started to get annoyed with Marquez at this point, and they pelted him with beer cans. “OK,” he said, holding his hands in the air in surrender. “We're going to give you some rap.” The audience paused, its expectations raised momentarily.

The first rap act was Actitud Maria Marta, a white rapper from Argentina known for her political raps. There was a buzz of amusement in the crowd as she climbed on to the stage. Her translucent white skin was artificially tanned, and her straight brown hair was braided into cornrows. The organizers couldn't give the crowd any black performersâthat was insult enoughâ but to now give them a white rapper in blackface? Maria Marta began her first song in a shouting rap, revealing her origins in the punk rock of the 1980s. But she paused halfway through, aware that she had lost the audience. Lacking the arrogance of the earlier male groups, she quietly left the stage.

Next on were DJ Trece and a blond punk rapper named Belica. Belica's eyes were bloodshot and she had trouble standing up straight.

“Anda fuma'o

,” Yajaira observed wrylyâBelica was high. Trece rapped in Spanglish: “With

sabor Latino agre- sivo

, you know my

estilo

/ Like

estilo neoyorquino

, baby, baby, listen to this / Come on, once again, I do it like this / Move your body, I'm ready for the party.” Belica swayed unsteadily on the stage to the music, unable to coordinate her movements to pick up the microphone. It was a farceâthe drugged-out performer, the marijuana being smoked around us, and all this at a “Say NO to Drugs” concert. Trece continued with his lame rap, until finally the audience had enough.

“Fuera, fuera”

they shouted. Duque and I exchanged smiles. It was somewhat gratifying to see the self-proclaimed founder of Venezuelan hip hop tuck his tail between his legs and walk off the stage in defeat.

The situation in the

parte baja

was growing more volatile. The shoving and jostling were getting vicious. Suddenly, a gunshot rang out. There was silence in the auditorium. Then people started running toward the exits and screaming. A space gradually cleared around a fallen body to the left of the stage. People watched in quiet dismay as a stretcher arrived and paramedics removed the lifeless form. Then the audience slowly reassembled on the floor, much more subdued than before.

“Welcome to the mouth of the wolf / Where in less than a second anything can happen / Murders, attacks, that is daily life in my barrio / Day and night, night and day,” El Nigga rapped in a low growl as he came up on the stage. The rap was accompanied by a discordant and ominous-sounding riff. The audience immediately became attentive. People clamored around the front of the stage, hanging on to every word. “Calle Carabobo, a labyrinth without exit / A subterranean zone where the mafia reigns / You can't avoid the bullets, they rise and fall / That's what it's like where I live.”

After Vagos y Maleantes, the rappers Colombia and Requesón from Guerrilla Seca were up with their song “Black Malandreo.” Colombia sported a green-and-gold Celtics cap and shirt, and Requeson had on a Los Angeles Clippers hat. “I go on desper-ately, looking for work is a joke,” rapped Requesón. “I make it home, my kids are crying. What's happening, my situation is getting worse.”

“Brother, what's happening?” asked Colombia.

“The hunger is killing us,” responded Requesón.

“Well, what are you thinking?

“I have my house, my kids crying of hunger and the pain that envelops me / What I want is to buy half a kilo of drugs and start a business.”

“The same thing will happen to you that happened to me.”

“To me! Don't you see that I don't give a shit anymore, and I'm talking to you in confidence / It's not for me but for my kids who have nothin.'”

“Guerrilla Seca represents, misery, poverty, shit,” they rapped together on the chorus. “This is the reality that can happen to you / What I live is

malandreo

, this is the real story.”

A hush had extended over the audience. I watched the faces of the young people in the crowd, drawn into the story that Guerrilla Seca was telling. It was their story. It struck me that this was one thing that the government didn't understand. Young people were hungering for representation and recognition, and that didn't always come with political slogans. Sometimes it just came when someone gave voice to their experiences. And despite Chavez's tremendous appeal to the masses, the cultural establishment was Eurocentric and out of touch with young people. Like these politicians, I had jumped the proverbial gun in expecting that gangsta rappers in Caracas would naturally be a part of a movement for revolutionary change. But, as Robin Kelley and others have warned in the context of the US, before deciding how gangsta rappers might or might not act politically, we first had to understand where they were at.

C

olombia and Requesón were much more subdued than Budu and Nigga. When we met in the offices of Subterranea Records, they spoke in low and somber tones, just like their hard-core and gritty music. Their influences were the American rappers Tupac, Nas, and Ludacris. Like the rappers from Vagos y Maleantes, they couldn't understand the English lyrics, but they said that there was a certain flow, a feeling associated with the music, that spoke to them.

When Requesón was twelve years old, he was part of the rap group Aracnorap, whose members would meet at Parque del Oeste and rhyme in the street. Several members of the group were lost to drug addiction or imprisoned, and Requesón contin-ued on his own. He later formed another duo with a rapper from the group La Realeza, but that rapper was wrongly convicted of murder and imprisoned shortly thereafter. It was then that Requesón met Colombiaâthe son of Colombian immigrantsâat a club in el 23 de Enero, and they began to perform together. After winning a rhyming competition at a club in the middle-class neighborhood of Las Mercedes in 1999, Requesón and Colombia formed the group Guerrilla Seca. They would freestyle together in Los Próceres, where they were eventually introduced to Juan Carlos.

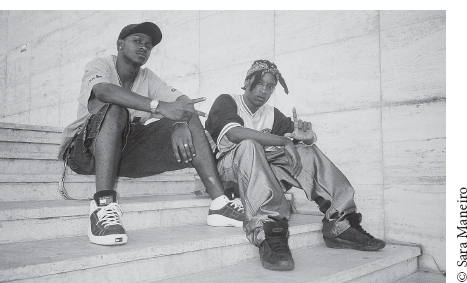

Colombia and Requesón of Guerrilla Seca. Los Próceres, Caracas, 2003

I was glad to have the chance to sit down with Colombia and Requesón. There was a question that had been bothering me, and it was something that I wanted to ask them. I had listened to their CD

La realidad mas real

countless times, and the themes of poverty, oppression, police brutality, and racism seemed to overlap with the concerns of underground rappers I had encountered around the world. It was satirical, caustic social commentary. But one song on the album seemed wildly out of place, “Voy a hacer plata” (I'm going to make money). The lyrics of this song sounded like something on the airwaves of New York's Hot 97 FM: “I'm going to make money / From when you're born till when you die, that's what it's about,” and “If I could make five million dollars a month I'd be a real millionaire /â¦I'd get gold teeth and I'd adorn myself in gold all over. I'd have a ton of Rolex, rings, chains for daily use.” And the last line truly offended my sensibilities as a feminist: “I'm going to make money,

whore”

“I just don't get it,” I told the rap duo. “The music all made sense till I got to that track. Why the focus on materialism and money as the ultimate goal?”

“The song talks about what weâtoday's generationâwhat we want and what we crave,” Colombia began. “We're clear that we live in a very materialist world and that the world of money is the focus. If the world was not so upside down, if everything was not about money, if everything was not so materialisticâ”

Requesón chimed in: “We're clear that we ourselves are not materialists, but we've never had anything. We are poor and we believe that we deserve something also for all our work. We are people who live in a barrio. We live in bad conditions and we want to get ahead, take our mothers out of poverty. We talk of money and Rolex watches and gold teeth because we don't have these things. We know there are things more important to sing about than a watch or a car. There are more important things like war or hunger. But we have to orient ourselves to where the conversation is at, because we want people to listen to us, and we want to bring reality into focus.”

Gangsta rappers were aware that they were coming of age in an era when personal worth was increasingly measured in terms of consumption and status symbols. If their potent brand of gangsta rap gave voice to experiences of marginality and poverty in an era of aggressive free-market capitalism, they also saw the free market as the only way to rise out of poverty. And the enterprise of making money was bound up with their masculinity and assertion of male dominance, as seen in their troubling references to women as whores. But as they spoke, I noticed the subtext of a more complex story about the degradations of class and race. The market was not just a way out of poverty but a way to prove one's worth and dignity as a human being in a society in which young black men from the barrio are treated as less than human.