Close to the Edge (24 page)

Authors: Sujatha Fernandes

“Now we are professionals and we can move up in life,” Requesón continued. “We want people to see us and respect us, or at least see that we are trying to move forward. You have something; you have earned something with your work and through your struggle.”

“The truth is that we, blacks, have always been oppressed,” Colombia said. “Racism exists in all countries. Here they'll âblacken' you just because of the clothes you wear. You get on a bus, and they look at you like, Is he going to rob me? But we have to fight to show that not all blacks are

malandros

, and not all blacks are delinquents, and not all blacks are involved in drug trafficking.”

Requesón agreed. “One hundred thousand people see you like that. Blacks

are

those who live in the barrio. Blacks

are

those who have suffered. Blacks

are

those who live in this world of violence. But they treat us like we're the bad ones because we're poor, because we don't have anything. And I think we deserve respect.”

Colombia and Requesón's assertion of black identity seemed to go against long-held myths that Venezuela was a

café con leche

, or coffee with milk, society, where all races coexisted and blended harmoniously. Even though there was tremendous seg-regation among the races, Venezuelans didn't have a tendency to see themselves in racial terms. Was race just an idea that hip hop culture was introducing? Or, as in Cuba, did hip hop give voice to divisions that were growing more acute with economic crisis? For Requesón race had always been important: “There are some who say that Venezuela is a mixed-race country and that we're all one race of Venezuelans. But back then, when they oppressed the black, they didn't see it as,

Coño

, he's from here, he's from our same country.' No, they didn't see it like that. They saw it as: âHe's black and we're gonna fuck him over âcause he's black, he's not from our nation.'”

Given this militant language, why didn't gangsta rappers mobilize and make demands for racial equality? One possible reason was Venezuela's distinct history. The absence of race- based organizing in the postcolonial period meant that there were no models to draw on. In Cuba there were several experiments in racial mobilizationâsuch as the Partido Independiente de Color, formed in 1908âbut there were no corresponding organizations in Venezuela. This may have been because slavery ended in Venezuela much earlier than in other countries, such as Cuba and Brazil. While slaves in Cuba and Brazil developed coherent religious systems such as SanterÃa and Candomblé, free blacks in urban areas of Venezuela began to absorb European culture and habits. Given the myth of a mixed-race, or

café con leche

, society during the postcolonial period, black identity and culture were even further submerged.

Another reason why gangsta rappers didn't organize was because they didn't have faith in the system to deliver racial equality. Unlike the Cuban rappers, who made demands on the state to live up to its promises of equality between the races, gangsta rappers in Caracas no longer trusted their corrupt politicians to lift them up from poverty and remedy racial discrimination. The solution was individual. They had to rely on their own forms of survival in the familiar terrain of the barrio. And they had to use their musical talents and entrepreneurial skillsâhoned through experiences in the drug trade and informal economyâto eventually bring themselves and their families out of poverty.

The members of Guerrilla Seca were not the urban revolutionary guerrillas of an earlier generation who would lay down their lives for justice. Rather, they were “straight-up guerrillas,” as their name impliedâthey didn't have anything, they didn't buy into anything. There was no utopian vision that was worth fighting or dying for. As Requesón rapped in his song “La calle” (The street): “The world is shit and I'm addicted to this shit.”

W

hen I returned to Caracas in January 2005, life had returned to somewhat normal. In the August referendum people had turned out in a large show of support for Chávez, defeating the recall motion, just like they had defeated the coup a few years earlier. They were not about to let their president be taken from them so easily.

I had heard about new voices that were emerging in Venezuelan hip hop, and I was curious to investigate further. I could understand the appeal of gangsta rap for barrio youth, but it seemed that the culture of violence was reproducing itself, a vicious cycle from which there was no escape. How could music help to liberate young people from this chain of events rather than convince them that it was the only possibility? I had no doubt that the hypermasculine culture of

malandreo

was an incubator for forms of political consciousness and social criticism. But it seemed that challenging entrenched inequalities going to take a lot more. Was black

malandreo

the only kind of black militancy that existed among barrio youth? Or were there other revolutionary black currents that were developing in tandem with Chavismo?

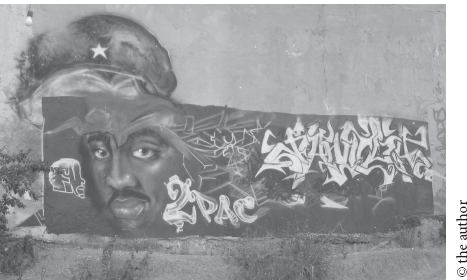

Tupac mural, La Vega

My curiosity took me to La Vega, a large mountainous parish on the outskirts of the city. I took a bus from El Valle along the highway Cota 905, passing through a terrain of green hills with overgrown grass, and trees and plants with rich foliage. It terminated at the Centro Comercial, a large shopping center at the entrance to La Vega. But the expensive boutique stores and fancy pastry shops in the shopping center were mostly for the wealthy residents of neighboring El Paraiso. Cars and buses sounded their horns as they jostled to leave or enter the parish. Vendors lined the street with large glass cases of sticky buns and iced donuts, surrounded by a halo of bees.

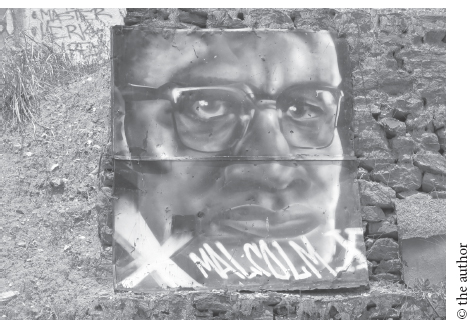

I followed the road as it veered to the left, approaching barrio Carmen and the headquarters of the Afro-Venezuelan cultural group Grupo Autoctono de la Vega. Just beyond the small brick headquarters was a mural of Tupac Shakur, with a faint outline of Che Guevara's signature beret sketched in the background. Next to this was a mural of the Venezuelan flag, covered in graffiti tags. On a large piece of metal someone had painted a portrait of Malcolm X. Farther along this road was a small church and plaza, where fiestas of the black saints are celebrated.

In the plaza I met Black 7, Aja, and Ricardo Sco, members of the rap group Familia Negra (Black Family). They were young men in their early twenties who wore gym pants and basket-ball jerseys. Aja lived in an apartment block facing the plaza. We climbed the stairs to his apartment, a clean and well-kept space where his mother served us sodas. After drinking the refresh-ments we ascended to the open-air rooftop encircled by low walls patched together from flat bricks and concrete. It looked onto a sea of other similarly constructed rooftops and a few taller blue housing projects to the left.

Black 7, Aja, and Ricardo Sco grew up learning about the Afro-Venezuelan fiestas like San Juan and Cruz de Mayo that were celebrated in the small plaza of barrio Carmen. Before the 1980s these fiestasâwhich consisted of drumming festivals and paradesâwere held mainly in rural provinces with large ex-slave populations. But in the 1980s urban cultural organiza-tions, like the Grupo Autoctono in barrio Carmen and other popular barrios, began to reclaim these cultural traditions as black culture and history. Local leaders like Williams Ochoa hoped to involve the young people of the barrio in the fiestas as a way of teaching them their cultural history and deterring them from a life of crime and violence. Black 7, Aja, and Ricardo Scó met through the Grupo Autoctono and carried its vision into their music.

Malcolm X portrait, La Vega

“We belong to the real underground in Venezuela,” Black 7 said. “What we do is different from what you hear in commer-cial hip hop.”

“The rap groups you see on television here, they're all plastic,” Aja added. “They wear baggy pants and jerseys, but it's all superexpensive gear because they're rich. Most of them are from the east of Caracas like DJ Trece. I'm not going to get up there and rap about being a

malandro

, because I don't live that in my reality. Me, for example, I'm a student and a worker. I can't turn into this rapper with a pistol and say that I'm the most

malandro

of all, that I live in a

cerro

and I was shot. I'd be invent-ing a fantasy. But that's what happens with a lot of rappers here.

“Society always wants to isolate us because we're against the system,” Aja went on, “just like our martyrs, our ideologi-cal leaders like Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Mandela, and Gandhi. We have suffered but we're not gonna suffer all our lives. We're going to open up paths. We're going to open the eyes of our fellow blacks. That's why we're called Familia Negra, because we try to raise the self-esteem of blacks who still today carry four hundred years of slavery in their blood.

“The constitution says that we're a multiethnic society, that here in Venezuela we don't have a defined race,” Aja continued. “We're all

indios

, blacks, Arabs, Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish. It's a mixture, but unfortunately many Venezuelans continue with discrimination, and they don't realize that this is not a pure country. We look for our roots because one of the first martyrs of Venezuela who fought for independence was Jose Leonardo Chirino, a black who you don't find mentioned in our history books. By contrast, in the United States they have something called Black History, and this is how you learn to love your skin color and raise your self-esteem.”

Aja's words resonated with me. In all my time in Venezuela, here, finally, was a perspective that I could fit into my under-standing of the hip hop planet as a generation of young people across the globe who shared certain basic principles and ideals and wanted to use the music to advance a socially progressive agenda.

Black 7 found a portable boombox and played one of the tracks from their self-recorded CD. The song started with a simple background beat, then Aja rapping. I did a double take. He was rapping in English: “Yo, Black Family baby, Black 7 in the revolution, building my family / Fucking lexicon in the country jungles / Oh Latina, my color black, oh my nigga.” Then he shifted into Spanish: “Representa mi gran poder, diversidad,” and back to English for a series of phrases that were unintelli-gible. They sang on the chorus, peppered with American slang, “It's black emcee / Black family, once again yo / I'm a tall black powerhouse, ya know what I'm sayin'.”

They watched me expectantly. I hid my disappointment with a plastered smile. The most progressive politics didn't always produce good music.

A

ll my travels seemed to confirm the idea that just as hip hop was very diverse in its origins, so it looked different as it spread across the globe. From the revolutionary rap in Cuba to Chicago's hard-core underground, Sydney's activist rap, and gangsta culture in Caracas, global hip hop was strongly shaped by local concerns. But did that mean that we were all so dif-ferent that we couldn't come together or find common themes like race, marginality, or opposition to the mainstream around which we could unite? Venezuela seemed the perfect place to explore such a possibility, with a government that was willing to fund it. In January 2006 the Bolivarian government convoked a global hip hop summit in Caracas, complete with workshops, panels, and concerts.

“Suyee, we're in Caracas,” Magia exclaimed over the phone. It had been years since I had seen my Cuban friends Magia and Alexey, who were invited to the summit. “We're scheduled to perform in the Rinconada at twelve-thirty today. Can you make it?”

“I'll be there!” I was excited to see them again and to be part of the summit that was bringing together hip hop artists from across Latin America and the globe for discussions of politics, art, culture, and how a global hip hop generation could be at the forefront of change. It fit nicely with my own quest.

Close to 12:30, I was approaching the Rinconada, a small auditorium behind the museum in the downtown Bellas Artes neighborhood of Caracas. Only a smattering of people were in the audience, and the stage did not seem to be set up for a show. I went to the front and inquired about the Cuban group Obsesion but was met with blank stares.