Close to the Edge (18 page)

Authors: Sujatha Fernandes

As they rapped, the Notorious Sistaz and Dr. Nogood began a call-and-response sequence with the hyped-up audience. “Just kickin' the flow so so, yippedy yo,” rapped Dr. Nogood, and the audience chanted back, “Go sistas, go sistas, No good, No good.” Nirvana strode across the stage in her combat boots, and with heads nodding all around she rapped, “In the âhood looking yella as we kick it to the fellas / Punk, you better recognize!”

Waiata and I were waiting in the wings, and we locked hands briefly before jumping on the stage. “We are at war,” declared Sista Souljah on the sample. “I turn the channels over in my head,” began Waiata, “and there I meet the nightmare.” The beat kicked in. “My mum's bleeding, she's nearly half dying / Alice cooks a stew and the dishes need drying / I woke up with bruises, couldn't walk to school / Marcia gets a boyfriend and my classmates think it's cool.” “The Brady Bunch, the Brady Bunch,” we chanted on the chorus, “I wanna see a black face. The Brady Bunch, this the way we say fuck the Brady Bunch.” The room resounded as people chanted on the last line with us. For a multiracial generation that was force-fed the saccharine images of white suburban American paradise, it was a moment of catharsis.

Waiata and the author at Hip Hopera, November 1995

Many aspiring rappers launched their careers at the Casula show; others said what they had to say and then moved on to other things. Looking back on the basic old-school rhymes, the hard-core beats, and the simple raw truth in the lyrics, it might be easy to dismiss the scene as one of youthful idealism. But it was also a unique place, where multiple histories and landscapes converged through the black American form of hip hop, where the pain and horror of forced Palestinian exile mirrored Aboriginal displacement and genocide. It was a moment before the Australian music industry started promoting mostly white male rappers, when women felt empowered to take to the mic. And it was a statement by an excluded generation that did not feel represented by politicians or by the media it consumed. But could this translate into a political movement?

Waiata performing at Hip Hopera, November 1995

The show ended with another freestyle session, everyone up on stage, including Khaled. The eleven-year-old Lebanese rapper Mega D from The Three Little Shits rhymed, “Yo, I decapitate the mic with my skills ya know / I can't wait till the next one tries to step to me / Can he really compete with the lyrical dictionary / At first glance, ya may say that I'm a criminal / âCause of my baggy pants and my shirt that's original.” He closed out his rhyme with “Now I gotta go, it's past my bedtime.”

I

n the period after Hip Hopera, I moved to Redfern, the inner-city neighborhood that was home to a large majority of Sydney's Aboriginal population. Bordered by a commuter railway station to the west and stretching to the busy thoroughfare of Elizabeth Street to the east, Redfern was a collection of narrow streets with Victorian two-story terrace houses. It was only a few miles from the central business district, and developers had begun to take an interest in available properties.

Redfern had historically been the site of a local black power movement, as young Kooris moving to the city en masse during the sixties in search of work began to hear about the Black Panthers, the Indians' occupation of Alcatraz, and decolonization movements in Africa. Rural migrants came from the north coast and western part of the state, and included Wiradjuri groups from central New South Wales.

Regent Streetâwith its famous pub the Empress Hotelâwas a hive of activity. Inspired by the community service work of the Black Panthers and faced with growing police abuse and harassment in the neighborhood, a group of Koori activists set up a legal services center on Regent Street in 1970, and a year later they started a free medical clinic. In the early seventies a group of Aboriginal writers and actors set up the Black Theatre in a warehouse on Regent Street, and their first activity involved street theater during a land rights demonstration. In the eighties Koori activists started Radio Redfern in a small house on Cope Street, broadcasting under the license of another station. In 1993 Radio Redfern was converted into Koori Radio.

During the mid- to late 1990s Redfern was undergoing a cultural renaissance of sorts. Koori artists held exhibitions in the empty warehouses along Redfern Street. In 1995 the American rapper Ice Cube visited Redfern to launch Koori Radio, and from then on it saw a constant stream of Aboriginal artists, activists, and musicians.

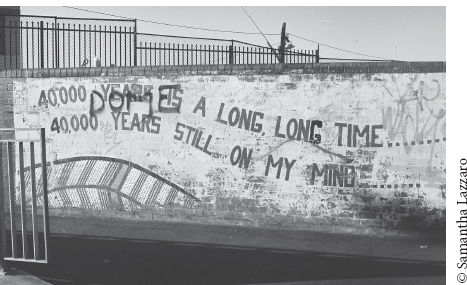

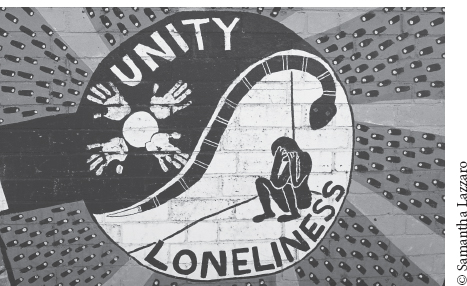

Spanning the length of the wall facing the Redfern train station was a mural by local Kooris that narrated the story of their journey to the present. “40,000 years is a long, long timeâ¦40,000 years still on my mind,” the mural began, referring to the known period that Aboriginal people had occupied the country. There was a symbol of a ship with several tall masts, representing the First Fleetâthe ships that came from Britain in 1788 to set up the colony. Here there was a thick black line down the center of the mural, marking a moment of rupture in the indigenous experience. Juxtaposed with a bush scene of gum trees and a naked Aboriginal boy standing before a Christian mission was a boomerang flying over a series of urban rooftops. There was the profile of an Aboriginal woman dressed as a domestic, with a look of mourning, black and yellow rays radiating out from her. On the opposite wall was a mural that read, “Say Know to Drugs: For The Next Generation.” It contained a black figure behind bars, with handcuffs painted in the surrounding border and the caption “Law and Order.” Next to it, an image of a curled snake creating a yin-yang type of symbol separated a figure sitting alone in a corner from a circle of hands showing “unity.”

Redfern mural

Redfern murald

Adjoining the mural was Eveleigh Streetâa section of row houses referred to as “the Block.” It was handed over to a self-organized collective of Aboriginal people known as the Aboriginal Housing Corporation in 1973, after a battle with local residents and landlords. It was one of the first experiments in Aboriginal-managed housing, breaking down fences to create shared living spaces.

7

Kooris migrating to the city saw the Block as a spiritual Mecca, an opportunity for affordable housing, and a way to retain kinship with other Kooris in the alien big city.

At the entrance to the Block, an Aboriginal flag flew from a flagpole, signaling that you were entering Aboriginal territory. There was an enormous mural of the Aboriginal flag painted on the side of a building: half black to represent Aboriginal people, half red for the crimson-brown soil of the land, and a yellow sun, the giver of life, in the center. The narrow houses with their wrought-iron balconies were set amid eucalyptus and tufts of overgrown grass, the skyscrapers of Sydney's downtown area visible in the background. There would be kids jumping rope in the street, teenagers sitting on stoops with boom boxes, older people outside relaxing in the shade, and, on occasion, people gathered around fires on the pavement at night. While in town to give concerts, visiting US rap artists such as Chuck D, The Fugees, and Michael Franti all have spent time at the Block.

At the same time police cars were permanently stationed at the entrance to Eveleigh Street and would make random incursions into the Block. White drug users from Newtown could be found shooting up in the alleyways or in search of the cheap drugs sold by Aboriginal children. When I once went to the local police station to report a bag of mine had been stolen, I walked out in disgust at the racist questioning of the police: “Did you see who it was? Was it a fuckin' Abo?”

Awakened by shouts in the early hours of the morning, I would look out from my window onto the back alley at brutal acts of violence, sometimes a taxi driver or hapless drunk being robbed for cash, sometimes only the black leather jacket of an officer visible as he pummeled his fists into a black kid. Every two weeks I would visit the Redfern social security office to collect my unemployment benefits, or “the dole,” since I was trying to finish my degree part time. A room full of jobless brown and black people stared blankly at a booming television set as they waited to be called to a social worker to describe their employment-seeking efforts and then pick up a check for $120.

It was at this time that the specter of white supremacy raised its head yet again in the form of a red-headed, blue-eyed owner of a fish-and-chips shop who hailed from the northern Queens-land town of Ipswich. Pauline Hanson ran for a seat in Australia's House of Representatives in March 1996. After publicly criticizing welfare benefits for Aboriginal people, she was elected to the safest Labor seat in the state. In her first speech to the House of Representatives on September 10, 1996, Hanson ranted that Aboriginal people enjoyed many privileges that ordinary white Australians did not have, and she claimed that Australia was in danger of being swamped by Asian immigrants.

In 1997 Hanson formed the One Nation party and published a tract,

Pauline Hanson: The Truth

, in which she presented Aboriginal people as “savage cannibals.” She argued that welfare policies for Aboriginals and immigrants had divided Australians and they needed to unite again as “One Nation”âhence the name of her movement and party. Hanson called for immigration and policies of multiculturalism to be abolished, blaming immigrants for high rates of unemployment and crime. While official state policies of multiculturalism had allowed immigrants some degree of social mobility for the previous two decades, the state paid lip service to respecting cultural difference, ignoring the tensions and racial hatreds underpinning Australian society. With Hanson those tensions were coming to the fore once again. The conservative Liberal Party government led by John Howard, who had been voted into office in 1996, followed Hanson and retracted policies of multiculturalism and sought to reverse earlier land rights concessions.

As the attacks on Aboriginal people mounted during the mid- to late 1990s, black leadership was in retreat. The active and vital movement of the sixties and seventies had been driven underground or co-opted. Ten years of rule by the Labor Party had seen the formation within the state bureaucracy of a black elite known as “Abcrats,” soon to be dismantled by the Howard government. The new generation of urban blackfullas, reared in the heady days of land rights marches and black power, turned to hip hop as a means of diversion and reflection as darkness descended. And, in a moment of serious crisis for an embattled community, rap came forth to speak truth to power.