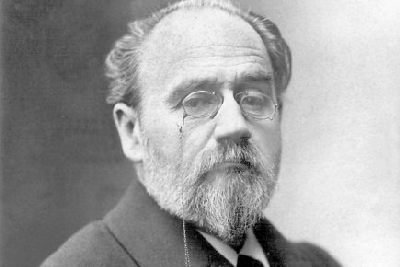

Complete Works of Emile Zola (1856 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

Authors: Émile Zola

But Clotilde does not answer anything like this. On the contrary, she eats at once the apple from this tree — passes soul and body into the doctor’s camp, and she does it because Zola wishes to have it that way. There is no other reason for it and cannot be.

Had she done that on account of love for the doctor, had this reason, which in a woman can play such an important part, acted on her, everything would be easy to understand. But there is no such thing! In that case what would become of all of Zola’s doctrine? It acts exclusively upon Clotilde, the author wishes to have only such a reason. And it happens as he wishes, but at the cost of logic and common sense. Since that time everything would be permitted: one will be allowed to persuade the reader that the man who is not loved makes a woman fall in love with him by means of showing her a price list of butter or candies. To such results a great and true talent is conducted by a doctrine.

This doctrine conducts also to perfect atrophy of moral sense. This heredity is a wall in which one can make as many windows as one pleases. The doctor is such a window. He considers himself as being degenerated from the nervousness of the family; it means that he is a normal man, and as such he would transmit his health to his descendants. Clotilde thinks also that it would be quite a good idea, and as they are in love, consequently they take possession of each other, and they do it as did people in the epoch of caverns. Zola considered it a perfectly natural thing, Doctor Pascal thinks the same, and as Clotilde passed into his camp, she did not make any opposition. This appears a little strange. Clotilde was religious only a little while ago! Her youth and lack of experience do not justify her either. Even at eight years, girls have some sentiment of modesty. At twenty years a young girl always knows what she is doing, and she cannot be called a sacrifice, and if she departs from the sentiment of modesty she does it either by love, which makes noble the raptures, or because she does it by the act of duty, but at the same time she wishes to be herself a legitimated duty. Even if a woman is an irreligious being and she refuses to be blessed by religion, she can desire that her sentiment were legitimated. The priest or

monsieur le maire

? Clotilde, who loves Doctor Pascal, does not ask for anything. Marriage, accomplished by a

maire

, seems to her to be a secondary thing. Here also one cannot understand her, because a true love would wish to make the knot lasting. That which really happens is quite different, in the novel, that first separation is the end of the relation between them. Were they married at least by a

maire

, they would have remained even in the separation husband and wife, they would not cease to belong to each other; but as they were not married, therefore at the moment of her departure he became unmarried, as formerly, Doctor Pascal, she — seduced Clotilde. Even during their life in common there happened a thousand disagreeable incidents for both of them. One time, for instance, Clotilde rushes crying and red, and when the frightened doctor asks her what is the matter, she answers:

“Ah, those women! Walking in the shade, I closed my parasol and I hurt a child. In that moment all of the women fell on me and began to shout such things! Ah, it was so dreadful! that I shall never have any children, that such things are not for such a dishcloth as I! and many other things which I cannot repeat; I do not wish to repeat them; I do not even understand them.”

Her breast was moved by sobbings; he became pale, and seizing her by the shoulders, commenced to cover her face with kisses, saying:

“It’s my fault, you suffer through me! Listen, we will go very far from here, where no one knows us, where everybody will greet you and you shall be happy.”

Only one thing does not come to their minds: to be married. When Pascal’s mother speaks to him about it, they do not listen to it. It is not dictated to her by woman’s modesty, to him by the care for her and the desire to shelter her from insults. Why? Because Zola likes it that way.

But perhaps he cares to show what tragical results are produced by illegitimate marriages? Not at all. He shares the doctor’s and Clotilde’s opinion. Were they married, there would be no drama, and the author wishes to have it. That is the reason.

Then comes the doctor’s insolvency. One must separate. This separation becomes the misfortune of their lives: the doctor will die of it. Both feel that it will not be the end, they do not wish it — and they do not think of any means which would forever affirm their mutual dependence and change the departure for only a momentary separation, but not for eternal farewells: and they do not marry.

They did not have any religion, therefore they did not wish for any priest; it is logical, but why did they not wish for a

maire

? The question remains without an answer.

Here, besides lack of moral sense, there is something more, the lack of common sense. The novel is not only immoral, but at the same time it is a bad shanty, built of rotten pieces of wood, not holding together, unable to suffer any contact with logic and common sense. In such mud of nonsense even the talent was drowned.

One thing remains: the poison flows as usual in the soul of the reader, the mind became familiar with the evil and ceased to despise it. The poison licks, spoils the simplicity of the soul, moral impressions and that sense of conscience which distinguishes the bad from the good.

The doctor dies from languishing after Clotilde. She comes back under the old roof and takes care of the child. Nothing of that which the doctor sowed in her soul had perished. On the contrary, everything grows very well. She loved the life, she also loves it now, she is resigned to it entirely; not through resignation but because she acknowledges it — and the more she thinks of it, rocking in her lap the child without a name, she acknowledges more. Such is the end of Rougon-Macquarts.

But such an end is a new surprise. Here we have before us nineteen volumes, and in those volumes, as Zola himself says,

tant de boue, tant de larmes. C’était à se demander si d’un coup de foudre, il n’aurait pas mieux valu balayer cette fourmilière gatée et miserable

. And it is true! Any one who will read those volumes comes to the conclusion that life is a blindly mechanical and exasperating process, in which one must take part because one cannot avoid it. There is more mud in it than green grass, more corruption than wholesomeness, more odor of corpses than perfume of flowers, more illness, more madness, and more crime than health and virtue. It is a Gehenna not only dreadful but also abominable. The hair rises on the head, and in the mean while the mouth is wet and the question comes, will it not be better that a thunderbolt destroyed

cette fourmilière gatée et miserable

?

There cannot be any other conclusion, because any other would be a madman’s mental aberration, the breaking of the rules of sense and logic. And now do you know how the cycle of these novels really ended? By a hymn in the worship of life.

Here one’s hands drop! It will be useless work to show again that the author comes to a conclusion which is illogical with his whole work. God bless him! But he must not be astonished if he is abandoned by his pupils. The people must think according to rules of logic. And as in the mean while they must live, consequently they wish to get some consolation in this life. Masters of Zola’s kind gave them only corruption, chaos, disgust for life, and despair. Their rationalism cannot prove anything else, and if it did, it would be with too much zeal, it would overstep the limits. To-day the suffocated need some pure air, the doubting ones some hope, tormented by uneasiness, some quietude, therefore they are doing well when they turn therefrom where the hope and peace flow, there where they bless them and where they say to them as to Lazarus:

Tolle grabatum tuum et ambula

.

By this one can explain to-day’s evolutions, whose waves flow to all parts of the world.

According to my opinion, poetry as well as novels must pass through it — even more: they must quicken it and make it more powerful. One cannot continue any longer that way! On an exhausted field, only weeds grow. The novel must strengthen the life, not shake it; make it nobler, not soil it; carry good “news,” and not bad. It does not matter whether this which I say here please any one or not, because I believe that I feel the great and urgent need of the human soul, which cries for a change.

BORLASE AND SON by James Joyce

1903

‘Borlase and Son’ has the merit, first of all, of’actuality’. As the preface is dated for May last, one may credit the author with prophetic power, or at least with that special affinity for the actual, the engrossing topic, which is a very necessary quality in the melodramatist. The scene of the story is the suburban district about Peckham Rye, where the Armenians have just fought out a quarrel, and, moreover, the epitasis (as Ben Jonson would call it) of the story dates from a fall of stocks incident upon a revolution among the Latin peoples of America.

But the author has an interest beyond that derivable from such allusions. He has been called the Zola of Camberwell, and, inappropriate as the epithet is, it is to Zola we must turn for what is, perhaps, the supreme achievement in that class of fiction of which ‘Borlase and Son’ is a type. In ‘Au Bonheur des Dames’ Zola has set forth the intimate glories and shames of the great warehouse — has, in fact, written an epic for drapers; and in ‘Borlase and Son’, a much smaller canvas, our author has drawn very faithfully the picture of the smaller ‘emporium’, with its sordid avarice, its underpaid labour, its intrigue, its ‘customs of trade’.

The suburban mind is not invariably beautiful, and its working is here delineated with unsentimental vigour. Perhaps the unc- tuousness of old Borlase is somewhat overstated, and the landladies may be reminiscent of Dickens. In spite of its ‘double circle’ plot, ‘Borlase and Son’ has much original merit, and the story, a little slender starveling of a story, is told very neatly and often very humorously. For the rest, the binding of the book is as ugly as one could reasonably expect.

The Biography

WITH ZOLA IN ENGLAND by Ernest Alfred Vizetelly

A STORY OF EXILE

CONTENTS

XV