Cyclopedia (34 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

OPPERMAN, Sir Hubert

Born:

Rochester, Australia, May 29, 1904

Rochester, Australia, May 29, 1904

Â

Died:

Knox, Australia, April 24, 1996

Knox, Australia, April 24, 1996

Â

Major wins:

Australian champion 1924, 1926â7, 1929; ParisâBrestâParis 1931; OBE 1952, knighted 1980

Australian champion 1924, 1926â7, 1929; ParisâBrestâParis 1931; OBE 1952, knighted 1980

Â

Nickname:

Oppy

Oppy

Â

One of AUSTRALIA's greatest sportsmen in any arena, “Oppy” was a pioneer who won hearts and minds in Europe in the 1920s then went on to a successful career in POLITICS after the Second World War. Opperman was a butcher's son who delivered telegrams on his bike, played Australian Rules Football and cricket at school, and was picked up at the age of 17 by Malvern Star Cycles. Opperman won four Australian road championships for the bike company, and his name was always to be associated with them. Through Malvern boss Bruce Small, who would remain his manager throughout his cycling career, he was introduced to Don Kirkham, one of two Australians to finish the 1914 TOUR DE FRANCE (the other being Iddo “Snowy” Munro). The 18-year-old Oppy soaked up Kirkham's tales of racing in Europe and set off in 1928 for his own campaign that would include the Tour de France, paid for in part by

a fundraising campaign in three newspapers in Australia and New Zealand. In the Tour, Opperman and his three teammates were at a huge disadvantage: most of the stages were TEAM TIME TRIALS in which they would struggle against 10-man squads while having to finish within each day's time limit. They also faced language difficulties: their manager was French and the race organizers would not permit him to talk to their translator, the journalist Rene de Latour, who wrote of “poor lonely Opperman being caught day after day by the various teams of ten super athletes, swopping their pace beautifully.” Even so, Opperman rode into Paris 18th overall, over eight and a half hours behind the winner Nicolas Frantz of Luxembourg. He was immediately invited to ride the Bol d'Or 24-hour race at the Buffalo velodrome in Paris, a nonstop event in which the stars were assisted by teams of pacers. There were two attempts to sabotage his bike by sawing through the chain, but his team manager found a heavy substitute machine to enable Oppy to win. He was warmly applauded for his ability to urinate while riding. He completed 909 km (565 miles) and was persuaded to keep going for another 79 minutes to add the world 1,000-kilometer record. So popular were his feats in France that he was voted athlete of the year by the readers of

L'Auto

, the paper that ran the Tour.

a fundraising campaign in three newspapers in Australia and New Zealand. In the Tour, Opperman and his three teammates were at a huge disadvantage: most of the stages were TEAM TIME TRIALS in which they would struggle against 10-man squads while having to finish within each day's time limit. They also faced language difficulties: their manager was French and the race organizers would not permit him to talk to their translator, the journalist Rene de Latour, who wrote of “poor lonely Opperman being caught day after day by the various teams of ten super athletes, swopping their pace beautifully.” Even so, Opperman rode into Paris 18th overall, over eight and a half hours behind the winner Nicolas Frantz of Luxembourg. He was immediately invited to ride the Bol d'Or 24-hour race at the Buffalo velodrome in Paris, a nonstop event in which the stars were assisted by teams of pacers. There were two attempts to sabotage his bike by sawing through the chain, but his team manager found a heavy substitute machine to enable Oppy to win. He was warmly applauded for his ability to urinate while riding. He completed 909 km (565 miles) and was persuaded to keep going for another 79 minutes to add the world 1,000-kilometer record. So popular were his feats in France that he was voted athlete of the year by the readers of

L'Auto

, the paper that ran the Tour.

In 1931, he returned for a second attempt at the Tour, finishing 12th, but, more significantly, he managed to win PARISâBRESTâPARIS, the first victory by a non-European in the toughest CLASSIC of the time. The race was run in rain and headwinds, but the biggest obstacle was simply staying awake through two nights on the road. Here Opperman admitted that he was helped by his experiences racing massive distances in Australian events such as SydneyâMelbourne: he banged his head with his hands, sang tunelessly every few minutes, and swallowed the coffee, tea, soup, and chops provided by Small. Incredibly, the 49-hour race came down to a five-man sprint on the Versailles velodrome, where Opperman won by 10 lengths.

In 1934, Opperman moved to Britain for a road-record campaign,

sponsored by BSA, who were linked to Malvern. He broke five distance records in a fortnight, including the END TO END from Land's EndâJohn O'Groats in 1934. He broke virtually every record on the books in Australia, setting a FreemantleâSydney time of 13 days, 11 hours, 52 minutes, and closing his career by smashing 100 records in a 24-hour attempt in Sydney.

sponsored by BSA, who were linked to Malvern. He broke five distance records in a fortnight, including the END TO END from Land's EndâJohn O'Groats in 1934. He broke virtually every record on the books in Australia, setting a FreemantleâSydney time of 13 days, 11 hours, 52 minutes, and closing his career by smashing 100 records in a 24-hour attempt in Sydney.

After serving in the war in the Royal Australian Air Force, he entered the Australian Parliament and was, variously, minister for transport, minister for immigration, and high commissioner to Malta. He continued cycling until the age of 90, and was actually on an exercise bike when he died.

P

PANTANI, Marco

Born:

Cesena, Italy, January 13, 1970

Cesena, Italy, January 13, 1970

Â

Died:

Rimini, Italy, February 14, 2004

Rimini, Italy, February 14, 2004

Â

Major wins:

Tour de France and Giro d'Italia 1998, eight stage wins in each; second, 1997 Tour; third, 1994 Tour; second, 1994 Giro; bronze medal, 1995 world road championships

Tour de France and Giro d'Italia 1998, eight stage wins in each; second, 1997 Tour; third, 1994 Tour; second, 1994 Giro; bronze medal, 1995 world road championships

Â

Nicknames:

Dumbo, the Little Elephant, Nosferatu, the Pirate, and Pac-manâbecause of the way he would gobble up rivals one by one en route to a mountaintop finish

Dumbo, the Little Elephant, Nosferatu, the Pirate, and Pac-manâbecause of the way he would gobble up rivals one by one en route to a mountaintop finish

Â

Reading:

The Death of Marco Pantani

, Matt Rendell, Phoenix, 2007

The Death of Marco Pantani

, Matt Rendell, Phoenix, 2007

Â

The charismatic and deeply troubled Italian was one of professional cycling's most celebrated climbing talents and one of its most distinctive stars thanks to his shaven head and big ears. He was one of a small minority to achieve the DOUBLE of wins in the GIRO D'ITALIA and TOUR DE FRANCE in the same year, but died a tragic death and came to epitomize the drug problems of the sport in the 1990s and beyond.

Pantani emerged as a professional in the 1994 Giro, taking second to Evgeni Berzin and showing MIGUEL INDURAIN a clean pair of heels in the mountains. In the 1994 Tour de France it was impossible to ignore him: he made dramatic attacks, fell off every now and then, and finished third. Every mountain inspired the same thought: when would Pantani make his move, and what would happen?

In 1995 he won two Tour stages, but suffered a horrific collision with a 4 Ã 4 while descending in the MilanâTurin; it was widely assumed that the compound fracture of his right shin had ended his career.

In April 1996 it had healed to a massive lump, with livid scars where the pins had been put in to stabilize the fracture. At that point he could only pedal a low gear, to avoid putting pressure on the leg.

In April 1996 it had healed to a massive lump, with livid scars where the pins had been put in to stabilize the fracture. At that point he could only pedal a low gear, to avoid putting pressure on the leg.

By July 1997 he had recovered sufficiently to win two mountain stages of the Tour and take second overall. His wins in the 1998 Giro d'Italia and Tour were inspiring after the DOPING scandal that hit the 1998 Tour. The legendary double put him on a level with the greats of cycling; overnight he became Italy's biggest sports star, with earnings estimated at £2 million a year. But his downfall came suddenly in June 1999 when he was thrown off the Giro d'Italia, at a point where a crushing victory was seemingly assured, for failing a blood test that indicated possible use of EPO. He was embittered for the rest of his life by the incident; he was convinced he had been unfairly targeted and could not believe the way that the cycling milieu turned its back on him.

Subsequently, officials found evidence he had used EPO; he was later banned for the use of insulin, found in a syringe when police raided the Giro. In 2000 he returned to cycling to complete the Giroâafter a papal reception in the Vaticanâand won the Mont Ventoux stage of the Tour, but during his spell in limbo he had acquired a cocaine habit that dogged him to his retirement in 2003 and beyond. “I'm fighting simply to get back my peace of mind and my love of the bike,” he said early that year. When he was found dead of a heart attack in a hotel in Rimini on Valentine's Day 2004 he was an addict whose friends had made numerous, fruitless attempts to clean him up.

Pantani's death has inspired a charitable foundation and an elaborate mausoleum in his home town, where his statue stands on the main square. There are also roadside MEMORIALS to recall some of his greatest exploits: on the Mortirolo and Fauniera passes in Italy and at the Deux Alpes ski resort in France. Two major CYCLOSPORTIVES, the Nove Colli and the Marco Pantani, go over climbs associated with him.

Â

(SEE ALSO

ITALY

,

DRUGS

)

ITALY

,

DRUGS

)

Â

PARALYMPIC CYCLING

Brought in as an Olympic sport in Seoul in 1988âfor road events onlyâwith the first track events in Atlanta in 1996. The UCI recognizes three categories of event in Disability Cycling: Blind and Partially Sighted (VI or B/VI), Cerebral Palsy (CP), and Locomotor (LC). Riders are assessed before their category is allotted. VI riders race on the back of a tandem with a fully sighted pilot. Races include flying 200 m, match sprint, kilometer time trial, and pursuit.

Brought in as an Olympic sport in Seoul in 1988âfor road events onlyâwith the first track events in Atlanta in 1996. The UCI recognizes three categories of event in Disability Cycling: Blind and Partially Sighted (VI or B/VI), Cerebral Palsy (CP), and Locomotor (LC). Riders are assessed before their category is allotted. VI riders race on the back of a tandem with a fully sighted pilot. Races include flying 200 m, match sprint, kilometer time trial, and pursuit.

CP is a condition occurring at birth that interferes with the development of the brain, affecting muscle tone and spinal reflexes. Brain injuries later in life can lead to the same symptoms, and these athletes compete with congenital CP cyclists. Locomotor athletes are divided into four categories depending on the level of limb disability; they can and often do compete on handcycles.

The GREAT BRITAIN cycling team has a dedicated paralympic section that dominated its events in Beijing in 2008, winning 17 gold medals and 3 silvers. Britain's leading cycling Paralympian is Darren Kenny from Dorset, a double gold medal winner in Athens and a triple gold medalist in Beijing in 2008. Kenny injured his neck in the RÃS Tour of Ireland aged 19 and returned to racing 11 years later merely in order to get fit.

PARISâBRESTâPARIS

Every few years strange sights are to be seen on back roads between Paris and Brittany: vast groups of cyclists with their bikes festooned with panniers riding through the night in great streams of cycle lights, bedraggled cyclists lining up outside school cafeterias and village

salles de fêtes

to fill up on carbohydrate-rich food, and,

oddest of all, men and women clad in lycra sleeping wherever they can by the roadside: in haystacks, hedges, doorways.

Every few years strange sights are to be seen on back roads between Paris and Brittany: vast groups of cyclists with their bikes festooned with panniers riding through the night in great streams of cycle lights, bedraggled cyclists lining up outside school cafeterias and village

salles de fêtes

to fill up on carbohydrate-rich food, and,

oddest of all, men and women clad in lycra sleeping wherever they can by the roadside: in haystacks, hedges, doorways.

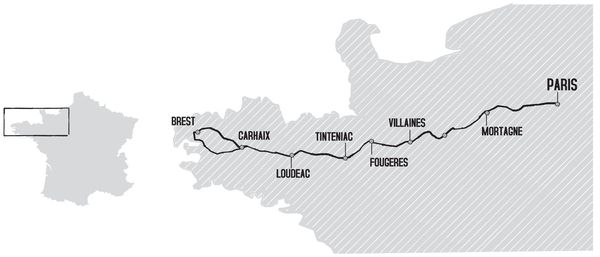

Such is ParisâBrestâParis, one of the great pioneering races when it was founded in 1891, now two different mass events run in four- and five-year cycles for several thousand cycle-tourists who don't mind a little sleep deprivation. In villages and towns along the 1,200 km route, the population turns out to watch the cyclists, who try to complete the event within the 90-hour limit. That means riding through the night, three times, with a few short naps along the way: sometimes in market halls, with labels at their feet to tell helpers when they want to be woken up. In parts of Brittany, local people still turn out to place candles in jam jars and tins to light the way into their villages at the dead of night.

PBP was founded in 1891 by the newspaper

Le Petit Journal

, as a test of bicycle reliability at a time when penny farthings were being supplanted by diamond frames. Charles Terront won the first race in 71 hours 22 minutes, with the aid of the 10 pacers placed along the route to help the riders. The race's distance, straight down Route Nationale 12 and back, was such that it was decided to organize it only once every 10 years. The great publicity line was that as the turn point was in the French

département

of Finistère, it could be billed as a race “to the ends of the earth.” The second edition, 1901, was won by MAURICE GARIN in just over 52 hours.

Le Petit Journal

was joined as sponsor by

L'Auto

; such was the paper's increase in sales that its editor HENRI DESGRANGE began looking for ideas for an annual event that would last even longer and be an even greater test of stamina: he and his colleague Géo Lefèvre came up with the TOUR DE FRANCE.

Le Petit Journal

, as a test of bicycle reliability at a time when penny farthings were being supplanted by diamond frames. Charles Terront won the first race in 71 hours 22 minutes, with the aid of the 10 pacers placed along the route to help the riders. The race's distance, straight down Route Nationale 12 and back, was such that it was decided to organize it only once every 10 years. The great publicity line was that as the turn point was in the French

département

of Finistère, it could be billed as a race “to the ends of the earth.” The second edition, 1901, was won by MAURICE GARIN in just over 52 hours.

Le Petit Journal

was joined as sponsor by

L'Auto

; such was the paper's increase in sales that its editor HENRI DESGRANGE began looking for ideas for an annual event that would last even longer and be an even greater test of stamina: he and his colleague Géo Lefèvre came up with the TOUR DE FRANCE.

The last pro PBP race was in 1951 and was won by Frenchman Maurice Diot in a record 38 hours 55 minutes, a time that still stands today. Randonneur and AUDAX events had begun

in 1931, and while the pro race could not draw enough entrants, the

touristes

kept turning up. The

randonneur

and audax events were run by different organizations until 1991 when the events were combined.

in 1931, and while the pro race could not draw enough entrants, the

touristes

kept turning up. The

randonneur

and audax events were run by different organizations until 1991 when the events were combined.

In 2003 some of the first male finishers were excluded from the closing ceremony and penalized two hours after finishing with the fastest times in the event's history. They had contravened various rules but more importantly were felt to have behaved in a way that contravened the spirit of the event, including “pushing the controllers at a control, urinating in a built-up area, not respecting red lights and stop signs on numerous occasions, using the lights of a following car illegally and not letting a controller's car pass.” In essence, those penalized had crossed the intangible line between a “tourist event,” in which a time may be taken but the spirit of the event is amicable, and a race, in which anything goes in order to be quickest from A to B.

Â

(SEE

CAPE TOWN

,

CYCLOSPORTIVES

, AND

ÃTAPE DU TOUR

FOR OTHER LONG-DISTANCE CHALLENGES)

CAPE TOWN

,

CYCLOSPORTIVES

, AND

ÃTAPE DU TOUR

FOR OTHER LONG-DISTANCE CHALLENGES)

Â

PARISâROUBAIX

The “Queen of Classics,”

La Pascale

, or simply the “Hell of the North,” this is the most coveted one-day CLASSIC of them all. All the MONUMENTS of cycling are founded on tradition: the inclusion of over 30 miles of COBBLES means that ParisâRoubaix is simply a throwback to the HEROIC ERA, when road surfaces played a key role in every cycle race. The event is not universally popular among professionals because of the risks involved: every year there are crashes on the cobblestones and a cyclist's entire season can be compromised. “

Une cochonnerie

,” was the verdict of BERNARD HINAULT. “A man's race,” said SEAN YATES, the best Briton in the event. “Cycling's last bit of madness,” according to the TOUR DE FRANCE organizer Jacques Goddet.

The “Queen of Classics,”

La Pascale

, or simply the “Hell of the North,” this is the most coveted one-day CLASSIC of them all. All the MONUMENTS of cycling are founded on tradition: the inclusion of over 30 miles of COBBLES means that ParisâRoubaix is simply a throwback to the HEROIC ERA, when road surfaces played a key role in every cycle race. The event is not universally popular among professionals because of the risks involved: every year there are crashes on the cobblestones and a cyclist's entire season can be compromised. “

Une cochonnerie

,” was the verdict of BERNARD HINAULT. “A man's race,” said SEAN YATES, the best Briton in the event. “Cycling's last bit of madness,” according to the TOUR DE FRANCE organizer Jacques Goddet.

The event was immortalized in one of the finest cycling FILMS ever: JORGEN LETH's masterpiece

A Sunday in Hell

. Today, it is a key event on the roster of Tour de France organizers AMAURY SPORT ORGANISATION, and French television devotes vast resources to covering it, including specially adapted motorcross bikes to get in-race footage and fixed cameras on the main cobbled sections.

A Sunday in Hell

. Today, it is a key event on the roster of Tour de France organizers AMAURY SPORT ORGANISATION, and French television devotes vast resources to covering it, including specially adapted motorcross bikes to get in-race footage and fixed cameras on the main cobbled sections.

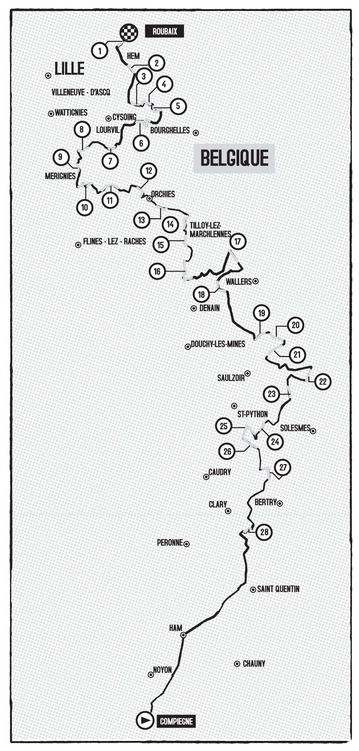

ParisâRoubaix goes back to 1896 and was originally run to publicize a newly built velodrome in an industrial suburb of the city of Lille. It was run on Easter Sunday in the face of opposition from the Church; to placate them, a mass was held at 4 AM before the start. The event still finishes on the velodrome although there have been brief flirtations with other finishes within Roubaix. The riders collapse on to the grass in the middle of the track after the finish; they are doing exactly what the first winner, the German Josef Fischer, would have done. Uniquely for a modern race, the riders shower off the mud and blood in an archaic washroom, where the press can interview them. No other Classic has stayed so close to its past.

Initially the cobbles were just

part of the route as they were in other races, but by the 1960s the organizers were actively seeking out cobbled sections to liven up the event. The turning point came in 1968 with the discovery of a horribly deformed, undulating track through the Wallers-Arenberg forestâclose to the coalmines that featured in Ãmile Zola's

Germinal

âthat has been the centerpoint of the race since then.

part of the route as they were in other races, but by the 1960s the organizers were actively seeking out cobbled sections to liven up the event. The turning point came in 1968 with the discovery of a horribly deformed, undulating track through the Wallers-Arenberg forestâclose to the coalmines that featured in Ãmile Zola's

Germinal

âthat has been the centerpoint of the race since then.

Now the cobbles are threatened by development and restricted to back roads through the fields, with bucolic names such as Prayers' Lane and Sugar Mill Lane. The Amis de ParisâRoubaix exist to maintain them, investing a lot of labor and about â¬15,000 a year. There are about 30 sections, all subtly different depending on whether the cobbles are slate (slippery) or granite (bad for punctures), uphill, downhill, well maintained, or badly drained and full of water. The decisive point today is about 20 km from the finish, the long, dragging section that leads to a lonely café at Carrefour de l'Arbre: the Crossroads of the Tree.

Other books

A Kind of Vanishing by Lesley Thomson

The Curse of the Pharaoh #1 by Sir Steve Stevenson

To Reach the Clouds by Philippe Petit

Dragon: A Bad Boy Romance by Slater, Danielle, Blackstone, Lena

Dark Dreamer by Fulton, Jennifer

Diana's Nightmare - The Family by Hutchins, Chris, Thompson, Peter

Chase by Dean Koontz

Shaman by Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff

Solfleet: The Call of Duty by Smith, Glenn

Casting Stones (Stones Duet #1) by L. M. Carr