Daily Life in Elizabethan England (23 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

Some wooden roofs were covered with lead to reduce the risk of fire, though again this increased the cost. The larger towns generally tried to forbid thatched roofs in favor of tile or wood covered with lead: a fire in the country might destroy only one house, but in the crowded conditions of the town it could lead to a major public disaster.

Doors were made of wood and might be secured with bolts, although

it was not uncommon even for ordinary people to have locks. A well-to-do family would have glass windows, made of many small panes held

together with lead. In poorer homes, there might be nothing more than the wooden shutters to close up the house at night, although cheap window filling could be made with thin layers of horn or oiled linen to let in light while keeping out the wind.

Important rooms would have a hearth for warmth or cooking. A poor

home might have a simple smoke hood above; most houses had some

form of chimney. This could be made of wattle and daub, but brick was preferred as it reduced the fire hazard. The hearth was lined with stones or bricks for the same reason.

Rural Homes

Only the very poorest country folk lived in a one-room cottage. Much more common was a two-room floor plan, which might measure around

30 by 15 feet. The front door led into an all-purpose hall, used for cooking, eating, and working. An inner door in the hall gave access to a parlor or chamber, which served as the sleeping-room for the householder and his wife; young children slept here too. Above these rooms would be a loft, providing storage and some additional sleeping space. A more prosperous home might have a full second story, with bedchambers above, in which case the parlor could be used for dining and entertaining visitors. There could also be additional side rooms for storage, food preparation, and similar tasks. Cellars were rare in country houses. In the simplest cottages, the floor might be no more than packed dirt, although those who could afford them had wooden floors. Access to upper levels was provided by ladders in simpler cottages or by permanent stairs in better cottages.

Rising standards of living for the yeoman class meant that many houses were being improved, usually by renovation, sometimes by rebuilding,

110

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

making them larger and better appointed than they had been before. A contemporary writing of Cheshire farmhouses in the 1580s observed that

“in building and furniture of their houses (till of late years) they used the old manner of the Saxons. For they had their fire in the midst of the house against a hob of clay, and their oxen also under the same roof. But within these 40 years it is altogether altered, so that they have builded chimneys, and furnished other parts of their houses accordingly.”3

The Croft

The country home was located on a small plot of land called a

croft.

In addition to the house, the croft included outbuildings such as animal sheds and pens, storage buildings for tools and provisions, and—in the case of a more prosperous householder—perhaps a separate kitchen, brewhouse, dairy, or bakehouse. There might also be barns for threshing harvested grain and granaries for storing it. The croft also supported a small garden. Here the woman of the house might raise flax and hemp for linen and canvas, hops for brewing, and whatever other plants she needed for household use: trees for fruits and nuts, vegetables, herbs for cooking and for household medicines, and perhaps some flowers. Some crofts had cobblestone courtyards, and walkways might be covered with sawdust to prevent them from becoming too muddy.

Domestic fowl such as chickens, ducks, and geese were kept on the croft, providing the family with meat, eggs, and feathers. Dairy cows and pigs might also be kept here. The farming household typically also had at least one dog (providing some protection against human and animal intruders) and a cat (to keep down the mice and rats that were inevitably attracted to the farmer’s grain). The smallest invited creatures in the country farm were the inhabitants of its straw beehives.

The Manor House

During this period the gap between the houses of the rich and the poor was increasing, as new and more elaborate styles of architecture evolved through which the wealthy could proclaim their social status. The medieval manor house, designed for defensibility, had given way in the 16th century to a more expansive and luxurious style that combined traditional medieval elements with new influences from Renaissance Italy. The stately Elizabethan home was typically based on an E or H shape, derived ultimately from the layout of medieval manor houses. The central section (the vertical part of the E or the horizontal part of the H) was a large hall, the principal public space of the house. It was flanked on one side by the family wing, which included the various private chambers of the family, and on the other by the service wing, which housed the kitchens, stores, and other working areas.

Material Culture

111

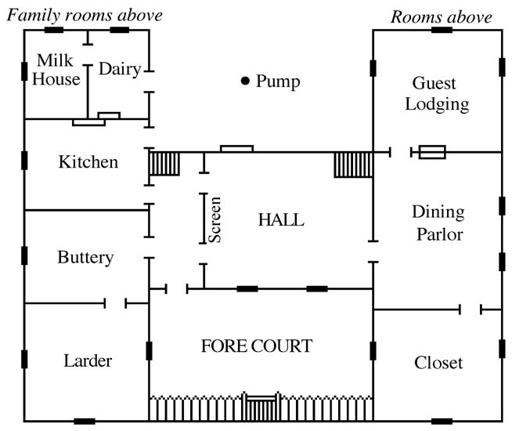

Design for an H-shaped country house for a prosperous commoner or a minor gentleman, after an early 17th-century design by Gervase Markham.

The

closet

is a private room for the family, the larder is for storing food, and the buttery for drinks. Private meals would take place in the dining parlor, public ones in the hall. The screen is a wooden partition dividing the hall from the passageway to the main door, the service rooms, and the family’s rooms above—it served to cut down on drafts. [Forgeng]

These houses were distinguished from their medieval predecessors by their open design. Aristocratic feuding and civil wars during the Middle Ages called for a compact structure surrounded by a stout wall, with the exterior walls of the house built to resist assault. By Elizabeth’s time only a light wall enclosed the grounds, and the building itself abounded in windows. However, many people continued to live in houses of medieval origin—the aristocratic manor hall of the Middle Ages had been solidly built, so that plenty of them still stood in Elizabeth’s day, although owners often attempted at least superficial alterations to adjust them to contemporary tastes.

The main residential building was surrounded by the facilities essential to the complex and cultured life of the aristocratic household. Kitchen gardens provided necessary herbs and vegetables for the household; these

112

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

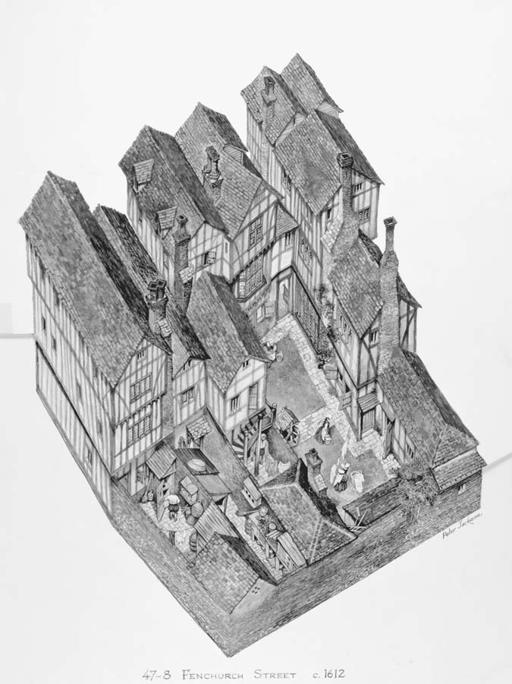

Reconstructed rear view of a block of London town houses on Fenchurch St., based on Ralph Tres well’s survey of 1612. At left are three narrow tenements belonging to William Jennings, Anne Robinson, and John Yeoman. Around the courtyard at right are two small street-front tenements held by James Dyer and James Sutton, and a long tenement beside the courtyard belonging to Jacques de Bees. Access to the courtyard was through a passageway to the street. [Peter Jackson, by permission of Mrs. V. Jackson-Harris]

Material Culture

113

were separate from the formal decorative gardens that were an expected feature of any aristocratic home. There would also be ancillary buildings such as bakehouses, brewhouses, barns, and stables. There might also be a dovecote: just before they learn to fly, the young of pigeons are easy to gather from the nest and are fat but unmuscled, making them perfect for the table—and the dung was used as an ingredient in gunpowder.

The Town House

The defining feature of the town house was a compact layout. Urban homes tended to be narrow, tall, and close together—they were often built as rows of connected structures. An ordinary home might be no more than 10 or 15 feet wide, although the plot of land might extend 50 feet or more back from the street, allowing for a garden in back and even space for keeping small livestock. Two or three stories were common, or even four; the upper floors might jut out into the street over the lower ones, creating additional floor space. There was likely to be a proper floor and a cellar.

If the owner of the town house was a tradesman or craftsman, the front of the ground floor might serve as a shop. The window shutter might swing downward into the street to create a kind of display counter, with a canopy overhead to protect against rain. The family slept above the main floor. Additional space in the upper floors might be occupied by servants or apprentices, or rented to laboring folk too poor to have a house of their own—taking on boarders was a common way for a family to supplement its income. Boarders, like servants and apprentices, were likely to eat with the family, as there were probably no separate kitchen arrangements.

At the top end of the urban housing scale was the courtyard residence of the wealthy household, with facilities similar to a rural manor house, but condensed into a four-square layout gathered around a courtyard.

Stairs and galleries went around the courtyard frontage of the structures, with access to the street through a passageway in the street-side structure.

Urban inns were also built on this plan, and some older courtyard residences had been broken up into multiple tenements, making something loosely analogous to a modern apartment block.

At the other end of urban architecture were the ramshackle homes of the poor at the margins of the town—particularly in the poorer areas of London. These buildings were built quickly and cheaply, often along lines similar to a poor peasant cottages.

Most urban neighborhoods were not segregated between wealthy and

poor areas. Instead, expensive dwellings tended to be those that fronted on main streets, with cheaper ones off side streets or alleys, or located in the upper floors of a building. Many urban buildings were subdivided into multiple tenements, and there could be quite a few layers of leasing between the owner of the land and the actual inhabitants of the building that stood on it.

114

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Living Spaces

The typical Elizabethan home allowed for very little privacy. Young children slept in their parents’ bedchamber, and servants sometimes in the same room as their employers. Four family members living in a two-room cottage had little private time, and a family living in town might share its space with servants, apprentices, and boarders. Things were different for the wealthy and privileged, whose houses had many rooms and ample opportunities for private space. Even so, such houses always had a significant domestic staff; their responsibilities were both in the working areas of the house and in the private areas, where they served as personal servants to the householder and family.

Home Interiors

The floors in a commoner’s house might be covered with straw or

rushes; a slightly more expensive option was decoratively patterned rush mats. Fragrant herbs or flowers might also be strewn upon the floors—

wormwood was sometimes included as a means of discouraging fleas.

Carpets were used as coverings for furniture rather than the floor, and only in well-to-do households. For decoration and extra warmth, the walls were often adorned with tapestries (for the wealthy) or with painted cloths (for the rest). These might depict biblical or legendary scenes; a painted cloth might even be based on folkloric themes such as the legend of Robin Hood. Alternatively, such scenes might be painted directly onto the walls.

Maps often adorned the walls in upper-class houses, and colored prints in all sorts of homes, while woodcut-illustrated ballads might be tacked to the walls of plebeian houses. Windows often had curtains, even in the houses of common folk.

Light and Heat

Although the average Elizabethan home was small and simple, it was not necessarily squalid. Even ordinary people took pains keep their houses in good order—in part because squalor invited vermin. The housewife used a broomstick (like the one now associated with witches) to keep the floor clean; if rushes or straw had been strewn, they were swept out periodically. When a goose died, the housewife saved the wing for dusting— the original feather duster!