Daily Life in Elizabethan England (21 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

products carried themselves: drovers were employed to drive herds of meat animals from the countryside to the towns—much of London’s diet walked to the city from as far afield as Wales.

The point of purchase varied depending on the locality and wares. The inhabitants of the larger towns had the best access, since there were plenty

98

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

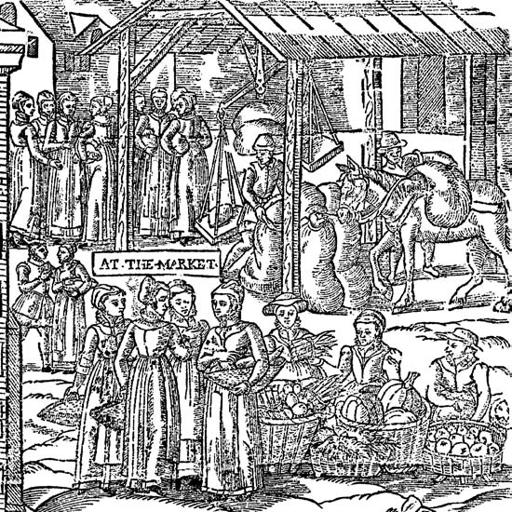

Marketing. [Besant]

of street vendors, markets, and shops to choose from. Country folk might buy wares at home from chapmen, traveling salesmen who circulated from village to village with small household wares. Alternatively, the villager could visit the nearest market town—there was usually at least one within 12 miles of any village . Here the country family could find craftsmen and retailers, although fewer than in a large city. Market-town retailers were therefore less specialized than their big-city counterparts: a draper might carry not only cloth but mercery wares, groceries, and stationery. Since the town also had a weekly market, this could also be an opportunity for the household to sell some of its own produce.

Many goods were purchased used rather than new. Crafted items like furniture and clothing were fairly expensive, since so much labor went into producing them, but they were often more durable than their modern mass-produced equivalents. Second-hand dealers bought and sold used goods, sometimes refurbishing them to improve their resale value. The same dealers often doubled as pawnbrokers—Philip Henslowe, owner of the Rose Theater in London, traded as a broker in this way. The cost of materials also encouraged recycling, which was also a significant element in the economy: building materials, cloth, leather, and metal were all subject to reuse, and the paper industry relied wholly on recycled linen rags.

Material Culture

99

Money

It is difficult to compare Elizabethan to modern money, since the economic parameters were very different. Labor was relatively cheap, while manufactured goods were expensive—there was almost no mechaniza-tion, so the vastly increased hours of labor more than negated the lower rate of pay. Moreover, prices could fluctuate enormously according to time and place. Prices today tend to be fairly constant because we have a well-developed system of transportation and storage. Elizabethans did not have the same opportunities to shop around, nor could they stock up on perishable goods when they were cheap and plentiful. In particular, the price of grain could vary hugely from harvest to harvest, impacting the rest of the economy much as energy costs do today. Prices were very sensitive to the supply and demand at a particular time and place, and predictably they were higher in London than in the country.

Overall, the late 1500s were a period of unprecedented inflation, albeit modest by modern standards. Over the half-century of Elizabeth’s reign, prices rose by about 100–150 percent. This was good news for some, bad for others. Substantial landholders whose production outweighed their expenditures profited: higher prices meant they could sell their surplus for more money. Small landholders, producing little or no surplus, were more at risk, since their income barely kept pace with their expenditures.

Above all, wage earners suffered from inflation, as the real value of their wages was eaten up by rising costs. By the early 1600s, the real wages of agricultural laborers were only half of what they had been two centuries before. Contemporaries were largely unable to accept inflation as a natural economic phenomenon: people still adhered to the medieval notion that everything had a

just price,

and that rising prices were the result of individual greed rather than impersonal market forces.

Elizabethan money consisted of silver and gold coins; even the smallest, the halfpenny, was worth more than most coins today. There was a pressing need for smaller denominations, but the halfpenny was already so tiny (about half an inch across) that a smaller coin would have been unusable. The problem was not solved until Elizabeth’s successor, James I, introduced brass coinage, although in the mean time some employers and tradesmen issued lead or copper tokens that could be accumulated and later redeemed from the issuer.

The typical Elizabethan coin bore an image of the Queen on one side and the royal coat of arms and a cross on the other. Its actual value was linked to the value of the gold or silver in it and was therefore susceptible to fluctuations in the prices of gold and silver, as well as to changes in the purity of the coins. When Elizabeth came to the throne, the value of English money had been undermined by repeated debasement of the coinage by her predecessors. Since the monarch could decide on the purity of the coin, it could be tempting for rulers to increase their short-term cash flow by reminting coinage at a lower purity, though this predictably led to

100

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Elizabethan coins: halfpenny, penny, sixpence, shilling, and gold crown. [Ruding]

intense inflation and financial turmoil. One of Elizabeth’s early measures was to restore English coinage to the

sterling

purity for which it had been known in the late Middle Ages.

The precious metal in the coinage was also a temptation to the unscrupulous. Coin clippers scraped tiny fragments off the edges of coins to accumulate the silver and gold (in later centuries coins would be milled with corrugated edges to make this kind of tampering easy to detect).

Since compromised coins undermined faith in the value of the monarch’s currency, clippers as well as forgers were subject to the death penalty if caught.

Some denominations were only

moneys of account,

used for reckoning but not actually minted as currency. Such was the mark, a large denomination used when dealing with substantial sums of money. The pound was also a money of account in that there were no pound coins, though there were coins that had the value of a pound. Other coins went in and out of production at various times: the farthing, worth a quarter of a penny, still existed under the earlier Tudors but was never minted during Elizabeth’s reign; the groat was minted at the beginning of her reign, but was soon replaced by a threepenny piece.

There was no paper money, although it was possible to deposit money with a banker or merchant in exchange for a letter of credit. In fact, credit played a major role in the Elizabethan economy. Neighbors, friends, and associates regularly loaned money to one another or sold goods on credit to those whom they had reason to trust. Those who could not get an unse-cured loan might turn to a pawnbroker if they needed to raise cash.

Material Culture

101

A tinker mends a pot. [Furnivall (1879)]

Table 5.1 offers some idea of the value of Elizabethan money. The table includes equivalents in modern US dollars, but these should be taken as rough magnitudes, not values. An Elizabethan halfpenny did not actually have the same purchasing power as a contemporary dollar, but it was more similar to a dollar than to a cent or to 10 dollars. The table also gives the Elizabethan abbreviations for various denominations—note that the normal abbreviation for a pound was

li.

(as opposed to the modern symbol £), which went after the number instead of before it.

A more meaningful idea of the value of these denominations can be

obtained by comparing them with wages and incomes. Wages might be

paid by the day, week, or year; the longer the term, the more likely that the wages included food and drink as well. In some cases, lodging was also part of the deal. Wages were regulated by law, although the theory was not always put into practice. The wages and incomes listed in Table 5.2 are only samples: actual wages and incomes varied according to time, place, and individual circumstances.1

Table 5.1.

Approximate Values of Elizabethan Money

Denomination

Value

Purchase Value

Equivalent

Silver

halfpenny (ob.)

½ of a penny

1 quart of ale

$1

Coins

three-farthings

¾d.

$1.50

penny (d.)

0.5 grams silver 1 loaf of bread

$2

three-halfpence

1½d.

1 lb. of cheese

$3

twopence

2d.

$4

(half-groat)

threepence

3d.

1 lb. of butter

$6

fourpence (groat)

4d.

1 day’s food

$8

sixpence (tester)

6d.

$15

shilling (s.)

12d.

1 day’s earnings

$25

for a craftsman

Gold

half-crown

2s. 6d.

1 day’s earnings

$60

Coins

for a gentleman

quarter angel

2s. 6d.

$60

angelet

5s.

$100

crown

5s.

1 week’s earn-

$100

ings for a craftsman

angel

10s.

1 lb. of spice

$250

sovereign

20s. (1 li.)

$500

(new standard)

sovereign

30s.

$750

(old standard)

German florin

3s. 4d.

$50

Dutch florin

2s.

$50

French crown

6s. 4d.

$150

Spanish ducat

6s. 8d.

$150

Moneys of

farthing (q.)

¼ of a penny

$.50

Account

mark (marc.)

13s. 4d.

$350

(⅔ of 1 li.)

pound (li.)

20s.

1 cart horse

$500

Material Culture

103

Table 5.2.

Sample Wages and Incomes

Shepherd’s Boy

2½d./day with food

Shepherd

6d./week with food

Unskilled Rural Laborer

2–3d./day with food

Plowman

1s./week with food

Skilled Rural Laborer

6d./day

Laborer

9d./day

26s. 6d./year with food and drink

Craftsman

12d./day, 7d. with food and drink

£4–10/year with food and drink

Yeoman

£2–6/year or more

Minor Parson

£10–30/year

Esquire

£500–1,000/year

Knight

£1,000–2,000/year

Nobleman

£2,500/year

30-acre landholder

£14, or a surplus of £3–5 after paying

for foodstuffs

Soldier

5d./day

Sergeant, Drummer

8½d./day

Ensign

1s./day

Lieutenant

2s./day

Captain

4s./day

The real value of incomes can best be judged by comparing them to the prices of goods (see Table 5.3). Purchasing was much less straightforward than it is today. Measurements were not always uniform throughout the country, and different goods might be measured by different standards: woolen cloth was purchased by the yard, but linen by the ell (45”). Prices were also subject to negotiation: haggling was the rule rather than the exception, except in the case of basic staples such as bread and ale, which were closely regulated.