Daily Life in Elizabethan England (16 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

The body was now ready for burial, but preparations for the living might take longer. Depending on the status of the deceased, the funeral might be an elaborate affair to which many people would be invited, requiring time to make the necessary arrangements. However, if the ceremony was delayed too long, the corpse might begin to decay. Typically, the funeral would take place within a day or two, although if more time were needed, a wealthy family could pay for embalming or a lead-lined casket to circumvent the problem of putrefaction. In the mean time, the corpse was watched constantly. In very old-fashioned communities this watching might be celebrated as a full-fledged wake, and could be an occasion for the kind of drinking and carousing that met with stern disapproval from religious reformers.

70

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

THE WILL OF ELLEN GARNET OF SUTTON, DERBYSHIRE, 1592

In the name of God, Amen, the 27th day of April in the 34th year of the reign of our sovereign Lady Elizabeth, by the grace of God of England, France, and Ireland Queen, Defender of the Faith,

etc.

I Ellen Garnet of Sutton, late wife of James Garnet deceased, being sick in body but in perfect remembrance, God be thanked for it, make this my last will and testament in manner and form following, that is to say, first I give and bequeath my soul into the hands of almighty God, my maker and redeemer, and my body to be buried in the parish churchyard of Prescot, as near to my friends as the ground will permit and suffer, and my funeral expenses to be made of my whole goods. Item, I give and bequeath to my son John Tyccle one brass pan, one coffer standing in the house, and one old long bolster. . . . Item, I give to Margaret Tyccle, wife of the said John, my best hat. Item, I give my daughter Anne Turner all the rest of my clothes except one old red petticoat which I give to Margaret Houghton. Item, I give further to Margaret Houghton 3s.

4d. Item, I give to Anne Lyon my daughter 40s. . . . Item, I give to my son Thomas Garnet all the rest of my goods movable and unmoveable. . . . Item I constitute, ordain, and make Thomas Garnet my son my true and lawful executor to see this my last will and testament done and executed in manner and form aforesaid. In witness whereof I the said Ellen Garnet have set my hand and seal the day and year first above written.

Mary Presland, ed.,

Angells to Yarwindles: The Wills and Inventories of Twenty-Six

Elizabethan and Jacobean Women Living in the Area Now Called St. Helens

(St. Helens: St.

Helens Association for Research into Local History, 1999), 11.

When it was time for the funeral, the corpse was laid in a casket, to be carried on a wooden bier; the bier was draped with a cloth called a pall. The parish normally provided the bier and casket, which were reused from one funeral to the next. Only the wealthy could afford to be buried in their own personal caskets; at most funerals, the corpse would be removed from the casket for burial. The bier was carried to the churchyard, where the priest met it at the gate to begin the religious ceremony of burial. Church bells would ring just before and after the ceremony.

The privileged would be buried inside the church under brass or stone markers bearing inscriptions of their names, and if they could afford it, some kind of inscribed portrait; the most expensive grave markers had fully carved effigies of the deceased in stone. Most people were buried in the churchyard in unmarked graves.

Funerals, like christenings and weddings, were important social occasions. For families that could afford it, the ceremony would be followed by a feast; food and alms were often distributed to the poor, while attendees would wear somber mourning clothes, often provided by the will of the deceased. Thomas Meade, a justice of the peace in Essex who died

Households and the Course of Life

71

in 1585, made arrangements of this sort: “There shall be bestowed at my burial and funeral one hundred pounds at the least to buy black cloth and other things, and every one of my serving men shall have a black coat; and a gown of black cloth to my brethren and their wives, my wife’s daughters and their husbands, my sister Swanne and her husband, my brother Turpyn and his wife, my aunt Bendyshe, and Elizabeth wife of John Wrighte.”12 In 1580, Essex gentleman Wistan Browne made provision that “at the day of my funerals dole be given to the poor people,

viz.

6d.

apiece to so many of them as will hold up their hands to take it, besides sufficient meat, bread, and drink to every of them.”13

As baptism and marriage were recorded in the parish register, so too was burial, the ceremony of the third and final great passage of life.

NOTES

1. Sir Thomas Smith,

De Republica Anglorum

(London: Gregory Seton, 1584), 19.

2. Gamaliel Bradford,

Elizabethan Women

(Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1936), 60.

3. On infant mortality, see E. A. Wrigley and R. S. Schofield,

The Population History of England 1541–1871

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981), 249.

4. Lu Pearson,

The Elizabethans at Home

(Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1957), 100.

5. D. M. Palliser,

The Age of Elizabeth

(London and New York: Longman, 1992), 7. On Elizabethan English, see Charles Barber,

Early Modern English.

The Language Library (London: André Deutsch, 1976).

6. Martin Ingram,

Church Courts, Sex, and Marriage in England, 1570–1640

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 300.

7. Roger Ascham,

The Scholemaster,

ed. Edward Arber (London: Constable, 1927), 57.

8. On literacy, see David Cressy,

Literacy and the Social Order

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 175–76.

9. On writing, see Myrial St. Clare Byrne,

The Elizabethan Home

(London: Methuen, 1949), 20; Giles E. Dawson and Laetitia Kennedy-Shipton,

Elizabethan

Handwriting 1500–1650

(New York: Norton, 1966); Sir Edward Thompson, “Handwriting,” in

Shakespeare’s England. An Account of the Life and Manners of His Age

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916), 1.284–310.

10. Palliser,

Age of Elizabeth,

426.

11. Steve Rappaport,

Worlds within Worlds: Structures of Life in Sixteenth-Century

London

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 234.

12. David Cressy,

Birth, Marriage, and Death. Ritual, Religion, and the Life-Cycle in

Tudor and Stuart England

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 440.

13. Cressy,

Birth, Marriage, and Death,

444.

4

Cycles of Time

THE DAY

For most Elizabethans the day began just before dawn, at cockcrow—or, strictly speaking, third cockcrow, since cocks would crow first at midnight and again about halfway to dawn. Artificial light was expensive and generally feeble, so it was vital to make the most of daylight. This meant that the daily schedule varied from season to season, dawn being around 3:30 a.m. in the summer and 7 a.m. in the winter. According to law, from mid-September to mid-March laborers were supposed to begin work at dawn, and in other months at 5 a.m. Markets typically opened at dawn, and businesses at 7 a.m.

Domestic clocks and portable watches were available to the Elizabethans, but they were expensive. Most people marked time by the hourly ringing of church and civic bells; there were also public sundials and clock towers. In the towns, time was invariably reckoned by the hour of the clock: normally only the hour, half-hour, quarter-hour, and sometimes the eighth-hour were counted, rather than the hour and minute—in fact, clocks and watches had no minute hands. In the country, people were more likely to reckon time by natural phenomena—dawn, sunrise, midday, sunset, dusk, midnight, and the crowing of the cock.

Mornings were always cold. Fire was the only source of heat, and household fires were banked at night as a precaution against burning down the home. If there were servants in the house, they rose first and rekindled the fires before their employers left the warmth of their beds; the servants

74

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

AN ETIQUETTE BOOK FOR BOYS

DESCRIBES THE MORNING ROUTINE

At six of the clock, without delay,

use commonly to rise,

And give God thanks for thy good rest,

when thou openest thine eyes . . .

Ere from thy chamber thou do pass,

see thou purge thy nose clean,

And other filthy things like case—

thou knowest what I mean.

Brush thou and sponge thy clothes too,

that thou that day shalt wear,

In comely sort cast up your bed,

lose you none of your gear.

Make clean your shoes and comb your head,

and your clothes button or lace.

And see at no time you forget

to wash your hands and face.

Hugh Rhodes,

The Boke of Nurture

[1577], in

The Babees Book,

ed. F. J. Furnivall (London: Trübner, 1868), 72–73.

might even warm their employers’ clothes. After rising, people would wash their face and hands. As there was no hot water available until someone heated it on the fire, most people had to wash with cold water (again, those who had servants could be spared this hardship). After washing, one was ready to get dressed—since people often slept in their shirts, this might just mean pulling on the overgarments. It was customary to say prayers before beginning the day, and children were expected to ask their parents’ blessing: they knelt before their parents, who placed a hand on their heads and invoked God’s favor.

Some people ate breakfast right away, while others did a bit of work first—a typical time for breakfast was around 6:30 a.m. The law allowed a half-hour break for breakfast for laboring people, and perhaps half an hour for a

drinking

later in the morning. Work was interrupted at midday for dinner, which took place around 11 a.m. or noon. By law, laborers were to be allowed an hour’s break for this meal, probably their main meal of the day.

After dinner, people returned to work. In the heat of the summer afternoon, between mid-May and mid-August, country folk might nap for an hour or two; the law provided for a half-hour break for sleep for laborers at the same time of year. It also allowed a possible half-hour drinking in the afternoon. Work would continue until supper; according to law, laborers were to work until sundown in winter (around 5 p.m. on the shortest

Cycles of Time

75

A SERVANT’S DUTIES AT BEDTIME

When your master intendeth to bedward, see that you have fire and candle sufficient. You must have clean water at night and in the morning. If your master lie in fresh sheets, dry off the moistness by the fire. If he lie in a strange place, see his sheets be clean, then fold down his bed, and warm his night kerchief, and see his house of office be clean, help off his clothes, and draw the curtains, make sure the fire and candle, avoid [put out] the dogs, and shut all the doors. . . . In the morning if it be cold, make a fire, and have ready clean water, bring him his petticoat [vest] warm, with his doublet, and all his apparel clean brushed, and his shoes made clean, and help to array him, truss his points, strike up his hosen, and see all thing cleanly about him.

Give him good attendance, and especially among strangers, for attendance doth please masters very well.

Hugh Rhodes,

The Boke of Nurture

[1577], in

The Babees Book,

ed. F. J. Furnivall (London: Trübner, 1868), 69–70.

day), 7 or 8 o’clock in the summer. For commoners, supper was generally a light meal relative to dinner.

Bedtime was typically around 9 p.m. in the winter, 10 p.m. in the summer. As in the morning, people would say prayers and children would ask their parents’ blessing before bed. Candles were extinguished at bedtime, although wealthy people sometimes left a single candle lit as a

watch

light

(the hearth was a good place for this). Household fires were banked: ashes from the hearth were raked over the burning coals, covering them just enough to keep them from burning themselves out, without allowing them to die entirely. As a result, nighttime tended to be very cold and dark—people usually kept a chamber pot next to the bed to minimize the discomfort of attending to nighttime needs! The wealthy often had special nightshirts, but commoners probably just slept in their underwear—shirts and breeches for men, smocks for women. A woman might wear a coif to keep her head warm, and a man might wear a nightcap.

Bedtime more or less corresponded to the hour of curfew, after which people were not supposed to be out on the streets. Both town and country streets tended to be very dark at night unless there was strong moonlight.

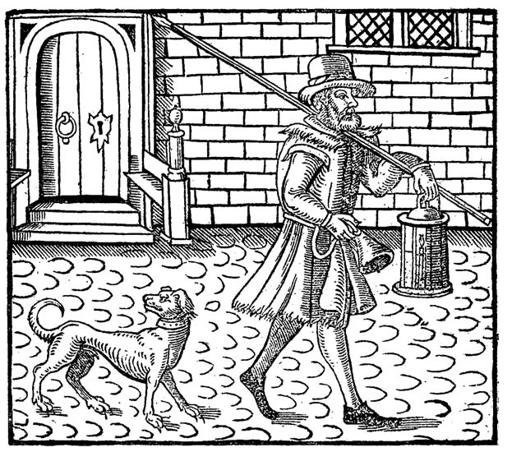

Some towns had laws requiring householders to put lanterns outside their doors, although this would have had little effect on the dark of a moon-less night. It was assumed that nobody who was outside at night had any honest business. Lone

bellmen

wandered the streets of the towns carrying a lantern, a bell to raise alarms, and a staff weapon for self-defense, keeping an eye open for possible fires or suspicious activity. They were supported by patrols of

watches,

civilian guards who could be summoned