Daily Life in Elizabethan England (13 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

One of the first things children needed to learn was how to trim their own pens. The pen and its accessories were kept in a leather case called a penner. People who had to do a lot of calculating, such as shopkeepers, often used a slate, which could be written on and wiped clear afterward.

Another form of temporary writing involved a wooden or metal stylus

Households and the Course of Life

55

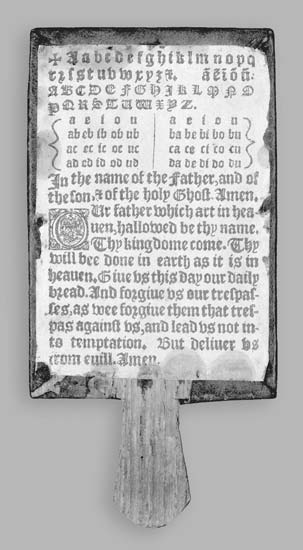

A hornbook. [By permission of the Folger

Shakespeare Library]

and a small thin board coated with colored wax, called a wax tablet. The writer would inscribe the letters into the wax with the stylus, which had a rounded end for rubbing out the letters afterward. Such tablets were typically bound in pairs (or even in books) to protect their faces, and were known as a “pair of tables.”9

There were two principal types of handwriting used by the Elizabethans, known as secretary and italic. The secretary hand had evolved in the late Middle Ages as a quick and workaday version of “Gothic” script. In the Elizabethan period it retained its workaday character, and was often used for correspondence, accounts, and other practical uses, although to the modern eye it seems very difficult to read. The italic hand was similar to the style of letters known as italic today. It had been developed in Renaissance Italy, and is much more clear and elegant by modern standards; it was especially used by learned people in scholarly contexts.

The alphabet was essentially the same as we use today, with a few interesting exceptions. For a start, there were only 24 letters. The letters

i

and

j

were considered equivalent:

J

was often used as the capital form of

i.

The letters

u

and

v

were similarly equivalent,

u

commonly being used in the middle of a word and

v

at the beginning. Where we would write “I have an uncle,” an Elizabethan might have written “J haue an vncle.” Some

56

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

A secretary hand. [Beau-Chesne]

Elizabethan letters have since dropped out of use. The normal form of

s

was the long form, which today is often mistaken for an

f

(it is not actually identical: the crossbar on the long

s

extends only on the left side of the letter, where it goes right through on an

f

). The modern style of

s

was used as a capital or at the end of a word. There was also a special character to represent

th,

which looked like a

y,

but actually came from an ancient runic letter called

thorn

: when we see “Ye Olde Tea Shoppe,” the

ye

should actually be pronounced

the.

Roman numerals were more frequently used than today, although reckoning was usually done with the more convenient Arabic numbers.

There were no dictionaries, so Elizabethan spelling was largely a matter of custom, and often just a matter of writing the words by ear. Still, the normal spelling of words was for the most part very similar to the spelling known today. The most obvious difference is that the Elizabethans often added a final

e

in words where we do not:

school,

for example, was likely to be written as

schoole.

In printed books there were two principal typefaces: blackletter and Roman. Blackletter type, like the secretary hand, was derived from medieval writing; it resembled what is sometimes called Old English type today. Roman type, like the italic hand, was associated with the revival of classical learning during the Renaissance and eventually replaced the blackletter entirely: the standard type used today derives from Roman

Households and the Course of Life

57

typeface. Italic type was also used, especially to set words apart from surrounding Roman text.

Grammar School

After petty school, if the family was rich or if the boy showed enough promise to earn a scholarship, he might go to a grammar school. This stage of schooling might last between 5 and 10 years, typically finishing by age 14 to 18. Some students might only remain for a year or two.

The grammar taught at a grammar school was Latin language and literature. For the first year or two the focus was on learning the elements of Latin grammar (

accidence

), after which the child was deemed ready to dive into Latin literature—in fact, older students were expected to speak Latin at all times and were punished for speaking English. Latin had long been Europe’s international language of learning, and grammar-school students read a mixture of ancient authors like Caesar and Cicero, religious writings, and modern scholarship, particularly the work of Eras-mus. Taken together, a student’s grammar school readings would amount to a broad-based course of study that could include material on literature, history, theology, geography, and sciences. The school might also teach a bit of French, Greek, or Hebrew. Teaching was through a combination of reading and interpreting aloud, translation exercises, and class activities such as debates and plays. In addition to literary studies, the curriculum often included music, and there might even be provision for sports such as archery.

All students at the school sat in one room, without desks: they were grouped on benches, called

forms,

according to their level of schooling.

Wolverhampton Grammar School in 1609 had 69 students, divided into an accidence class followed by six forms; students in the upper forms helped out in teaching the lower ones. The typical grammar school was headed by a master, usually a university graduate. The master might have one or more assistant teachers, called ushers, to assist him. At Wolverhampton, the master taught the top four forms, and the usher the lower two forms and the accidence class. The school often had a mix of paying students and poorer boys funded by scholarship. The Merchant Taylors’ School in London, a leading grammar school founded in 1561, had 100 boys who paid 5s. a quarter, 50 partial scholars paying 2s. 2d., and 100 boys who paid no tuition, although all were required to pay a 12d. entrance fee to the cleaner hired to keep the school tidy.

It was rare for a girl to be admitted to a grammar school, and such an arrangement would only last from the age of 7 to 9 or thereabouts. However, there were also some specialized boarding schools for girls.

School hours were long. A typical school day would begin at 6 a.m., with a 15-minute break for breakfast at 9 a.m. or so. There would be another break for dinner at 11 a.m., with classes resuming at 1 p.m.; then a 30-minute

58

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

break at 3 p.m. or so, with classes ending at 5 p.m. or so. Classes in the winter tended to begin an hour later and finish an hour earlier than in the summer.

Depending on the school, the boys might be day students, boarders, or a mix of both. Day students generally went home for their meals; boarding students slept in common dormitories. Classes ran year-round, but students might have Thursday or Saturday afternoons off, as well as two-week holidays at Christmas and Easter.

In addition to these publicly available forms of schooling, wealthy families sometimes hired tutors for their children. A tutor might provide the child’s entire education, especially for girls; in other cases, a tutor might cover subjects not included in the school curriculum. For example, if you wanted your child to learn modern languages, you might have to hire a tutor (except in larger towns, where there were often specialized schools for such purposes). This would be important for an upper-class family, whose children would be expected to learn at least some French, and perhaps Spanish or Italian as well. French had enjoyed a privileged place in English and European culture since the Middle Ages, and anyone of social pretensions was expected to be able to use it, while the cultural ascendancy of Italy during the Renaissance had given Italian a similar kind of cachet. Moreover, foreign languages were essential to Englishmen who were wealthy or important enough to travel abroad or have international connections, since few people outside of the British Isles bothered to learn England’s provincial tongue.

Tutors were also hired to teach nonacademic subjects like dancing and music; a boy might also be taught fencing, riding, swimming, or archery.

A girl’s education was likely to focus on such skills and graces as would make her a desirable match, notably modern languages, needlework, and music. Book learning was not generally a high priority for girls, although plenty of parents ensured that their daughters had a good education—

A GRAMMAR-SCHOOL TEACHER ON

THE EDUCATION OF GIRLS, 1581

To learn to read is very common, where convenientness doth serve, and writing is not refused where opportunity will yield it. Reading if for nothing else . . . is very needful for religion, to read that which they must know and ought to perform . . . Music is much used, where it is to be had, to the parents’ delight . . . I meddle not with needles nor yet with housewifery, though I think it and know it to be a principal commendation in a woman to be able to govern and direct her household, to look to her house and family, to provide and keep necessaries though the goodman pay, to know the force of her kitchen for sickness and health in herself and her charge.

Richard Mulcaster,

Positions

(London: Thomas Chare, 1581), 177–78.

Households and the Course of Life

59

Elizabeth herself was noted for her learning and was expert in both Greek and Latin. For some upper-class children, at least a part of this education might be acquired while living away in the household of a higher-ranking aristocrat.

Universities

After grammar school, a boy might pursue higher learning. University education in the Middle Ages had been almost exclusively the preserve of the clergy, but the 16th century witnessed a rising tide of secular students. Sons of the aristocracy came seeking the sophistication required of a Renaissance gentleman, and bright young men of lesser status came to prepare themselves for an intellectual career.

There were only two universities in England, Oxford and Cambridge, each subdivided into a number of semi-independent colleges that provided both lodging and teaching. The typical age of matriculation was 17

or 18; all students were boys. During the 1590s, Oxford took in around 360

new students each year.

The four-year course of study for a Bachelor of Arts included two terms of grammar (i.e., Latin grammar), four terms of rhetoric, and five terms of logic, or

dialectic,

as well as three terms of arithmetic and two of music.

Candidates for the Master of Arts studied Greek, astronomy, geometry, philosophy (including natural philosophy, which we would call science), and metaphysics; the degree normally required another 3 years of study.

Doctorates, which took 7 to 12 years, were available in divinity, civil law, and medicine. Degrees were awarded by the university, which offered lectures in the prescribed subjects and required graduating students to participate in disputations by way of a final exam. However, the bulk of the real teaching happened within the colleges under the tutor system. Each student was taken on by a

fellow

of the college, who guided the student’s reading and met with the student periodically to discuss his studies.

However, not every student took a degree. Many of the attendees were the sons of gentry families looking to acquire a smattering of learning before moving on: in 1604 the young gentleman Thomas Wentworth was advised by his father, “All your sons would go to the university at 13 years old and stay there two or three years, then to the Inns of Court before 17

years of age, and be well kept to their study of the laws.”10

Specialized Education