Daily Life in Elizabethan England (37 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

John Dover Wilson,

Life in Shakespeare’s England

(Harmondsworth: Pelican, 1951), 231.

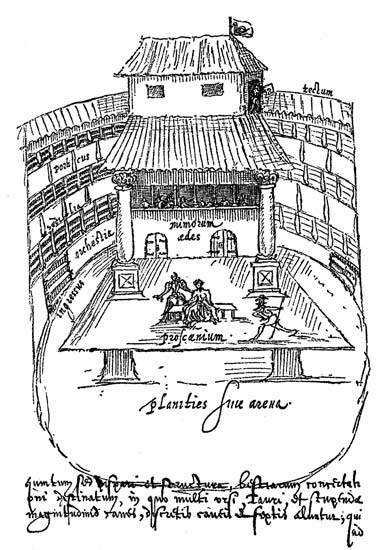

Fortune in 1600. In 1598–99 the Theatre was dismantled and moved to the emerging theater district in Southwark, on the south bank of the Thames, where it reopened as the Globe.

These early theaters resembled the innyards from which they had

evolved. They were built around courtyards, with three-story galleries on three sides, facing a stage that projected out into the yard. People sat in the galleries, while the less privileged stood on the ground; a few ostentatious young gentlemen might sit on the stage itself. The plays were attended by all manner of people. Aristocrats were often to be found in the galleries, while standing room on the ground was certainly within the means of most people. General admission cost only a penny, the price of two quarts of beer—the price of going to the theater was analogous to going to the cinema today, although the low wages of working people meant they could not do it very often. The Swiss visitor Thomas Platter in 1599

described the experience of a London theater:

The playhouses are so constructed that they play on a raised platform, so that everyone has a good view. There are different galleries and places, however, where the seating is better and more comfortable and therefore more expensive. For whoever cares to stand below only pays one English penny, but if he wishes to sit he enters by another door, and pays another penny; while if he desires to sit in the most comfortable seats which are cushioned where he not only sees everything well, but can also be seen, then he pays yet another English penny at another door.

186

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

The Swan Theater in 1596.

[

Shakespeare’s England

]

And during the performance food and drink are carried round the audience, so that for what one cares to pay one may also have refreshment. The actors are most expensively and elaborately costumed; for it is the English usage for eminent lords or knights at their decease to bequeath and leave almost the best of their clothes to their serving men, which it is unseemly for the latter to wear, so that they offer them for sale for a small sum to the actors.2

Plays had to be licensed, and government authorities were always wary of the overcrowding, plague, and disorder associated with play going.

In fact, laws against vagrants were often used against actors and other performers, who lived wandering lives, unattached to any employer or household. In response, theatrical companies placed themselves under the patronage of the great noblemen of England, which allowed players to avoid punishment by becoming, technically, servants of the lord. Shakespeare’s company were known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men during

the 1590s, and after the accession of James I they would become the King’s Men.

There was a constant and insatiable demand for plays, and actors became celebrated figures—the first stars. The plays’ action combined humor and violence along with musical interludes and dazzling special effects—not unlike modern popular films. Playwrights were typically university grad-Entertainments 187

uates, and their lives could be short and turbulent. Christopher Marlowe took Elizabethan audiences by storm. His

Tamburlaine the Great

(1587–88), full of violence, ambition, and horror, was the blockbuster of its day. William Shakespeare began his theatrical career late in Elizabeth’s reign, in the early 1590s with works including his history plays,

Romeo and Juliet

and

Midsummer Night’s Dream;

Ben Jonson entered the scene later in the same decade.

In addition to the permanent theaters in London, there were less formal settings for theatrical performances. The London companies occasionally toured the smaller cities and towns, performing in innyards and civic halls, and there were plenty of minor performers, part-time folk players, puppeteers, magicians, acrobats, and other entertainers.

LITERATURE

The other principal form of commercial entertainment was literature.

Elizabethan presses churned out all manner of texts: technical works, political and religious tracts (some of them considered highly seditious by the authorities, who punished the authors severely if they were caught), ballads, almanacs, histories, and even news reports. These texts varied in format from lavish volumes richly illustrated with fine engravings—

sometimes even colored by hand—down to cheap pamphlets and

broadsides

(single printed sheets) illustrated with simple woodcuts, produced for the mass market and selling for just a penny. The volume of printed material expanded substantially: from the arrival of printing in England in the 1470s to Elizabeth’s accession, a bit over 5,000 books were published of which copies still survive; from 1558 to 1579, the figure is 2,760; and from 1580 to 1603, it is 4,730. Readership was not limited to those who purchased copies, or even to those who could read them, since people sometimes read aloud in groups.

The most important text to the Elizabethan reader was the Bible. The law required a copy to be kept in every church, along with the

Book of

Common Prayer

, which described the liturgy of the church of England.

The Bible was the one book you would count on finding in any literate household. The most popular version was the translation known as the Geneva Bible, which appeared at about the time Elizabeth came to the throne; the version authorized by the English church was the Bishops’

Bible of 1568, which was less reformist in tone. Perhaps the second most common volume on the bookshelf in an English home was John Foxe’s

Acts and Monuments of these Latter and Perilous Days, Touching Matters of the

Church

—familiarly known as the

Book of Martyrs.

First published in 1563

and reissued many times thereafter, Foxe’s work told of the faithfulness of English Christians throughout history, with special emphasis on Protestants who had died under the persecutions of Bloody Mary. The law also required a copy of Foxe to be kept in the parish church.

188

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

MUSIC

If theater and literature were predominantly consumer entertainments, most other Elizabethan pastimes involved people as producers as well as consumers. Perhaps the most prominent example is music. The Elizabethans, like people today, liked to hear music. Unlike people today, they had no access to recording technology: all music had to be performed live.

To some degree, people made use of professional musicians to satisfy their desire for music. A wealthy householder might hire musicians to play during dinner, and major towns had official musicians known as

waits

who sometimes gave free public concerts—beginning in 1571, such concerts were given at the Royal Exchange in London after 7 p.m. on Sundays and holidays.

For the most part, people made their own music. Laborers and craftsmen sang while working; gentlefolk and respectable townspeople sang part-songs or played consort music after a meal. Barbershops kept musical instruments so that patrons could entertain themselves while they waited. The ability to hold one’s own in a part-song or a round (known to the Elizabethans as a

catch

) was a basic social skill. In fact, musical literacy was expected in polite society, and well-bred people could often play or sing a piece on sight. Even those of Puritanical leanings found pleasure in singing psalms; the reform-minded Lady Margaret Hoby liked to sing, accompanying herself on a lute-like instrument called the orpharion.

Favored instruments among the upper classes included the lute, the vir-ginals (a keyboard instrument in which the strings are plucked rather than struck), the viol (resembling a modern viola or cello), and the recorder.

Among common folk the bagpipe was popular, especially in the country; other common instruments were the fiddle and the pipe-and-tabor (a combination of a three-hole recorder played with the left hand and a drum played with the right). Public music was most often performed on loud instruments such as the shawm (a powerful double-reeded instrument) and sackbut (a simple trombone). In the countryside, the ringing of church bells was a popular pastime.

DANCING

Dancing was also a common entertainment. It was considered a vital skill for an aristocrat (the Queen was said to look favorably on a man who could dance well), but was equally important to ordinary people: it was not merely a pleasant diversion but one of the best opportunities for interaction between unmarried people. The Puritan moralist Phillip Stubbes complained in his

Anatomy of Abuses

,

What clipping and culling, what kissing and bussing, what smooching and sla-vering one of another, what filthy groping and unclean handling is not practiced everywhere in these dancings?3

Entertainments 189

THE PURITAN CRITIC PHILIP STUBBES

DESCRIBES MORRIS DANCING AT A PARISH ALE

All the wild-heads of the Parish . . . choose them a Grand-Captain . . . whom they ennoble with the title of “my Lord of Misrule,” and him they crown with great solemnity, and adopt for their king. This king anointed chooseth forth twenty, forty, threescore or a hundred lusty guts, like to himself, to wait upon his lordly Majesty, and to guard his noble person. Then every one of these his men he investeth with his liveries of green, yellow, or some other light wanton colour. . . They bedeck themselves with scarves, ribbons

& laces hanged all over with gold rings, precious stones, & other jewels; this done, they tie about either leg 20 or 40 bells, with rich handkerchiefs in their hands, and sometimes laid across over their shoulders & necks, borrowed for the most part of their pretty Mopsies & loving Besses, for bussing [kissing]

them in the dark. Thus all things set in order, then have they their hobby-horses, dragons & other antiques [spectacles], together with their bawdy Pipers and thundering Drummers to strike up the devil’s dance withall.

Then march these heathen company towards the Church and Churchyard, their pipers piping, their drummers thundring, their stumps dancing, their bells jingling, their handkerchefs swinging about their heads like madmen, their hobby horses and other monsters skirmishing amongst the route. . . .

Then . . . about the Church they go again and again, & so forth into the churchyard, where they have commonly their Summer-halls, their bowers, arbors, & banqueting houses set up, wherin they feast, banquet & dance all that day & (peradventure) all the night too.

Phillip Stubbes,

The Anatomie of Abuses

(London: Richard Jones, 1583), 92v-93r.

The preferred type of dancing varied between social classes. Those of social pretensions favored the courtly dances imported from the Continent, especially Italy and France. These dances were mostly performed by couples, sometimes by a set of two couples; they often involved intricate and subtle footwork. Ordinary people were more likely to do the traditional country dances of England. These were danced by groups of couples in round, square, or rectangular sets, and were much simpler in form and footwork, relatives of the modern square dance. The division was not absolute: ordinary people sometimes danced almains, which were originally a courtly dance from France, while Elizabeth herself encouraged country dances among the aristocracy. In addition to social dances, there were performance and ritual dances. Foremost among these was morris dancing, characterized by the wearing of bells, and often performed as a part of summer festivals.

HUNTING AND ANIMAL SPORTS

Elizabethan pastimes were not all as gentle as music and dance. One of the preferred sports of gentlemen was hunting—particularly for deer,