Daily Life in Elizabethan England (35 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

Henry Bull,

Christian Prayers

(New York: Johnson Reprint Co., 1968), 54–55, 58.

did not sit on the table but on a sideboard: a thirsty diner would summon a servant to provide him with a cup, which was taken away once he had drunk from it. The bond created by sharing of food and drink was emphasized by the custom of toasting and pledging with one’s drink. In humbler homes, it was common for children to serve their parents before sitting down to eat, and they were likewise expected to clear away the food at the end of the meal.

Men draped their napkins across one shoulder, while women kept their napkins on their laps. Manners books warned children not to smack their lips or gnaw on bones, to keep their fingers clean with their napkins, and to wipe their mouths before drinking. Once the meal was over, it was customary to recite another prayer and to wash hands again. People might clean their teeth at this point with a toothpick made of wood or ivory, turning away from the company and covering the mouth with a napkin while doing so.

Food and Drink

175

EATING OUT

When not at home, Elizabethan folk could get food and drink at taverns, inns, alehouses, and

ordinaries.

An inn was primarily a place for lodging, but also offered food, ale, beer, and wine. The tavern generally provided respectable lodging, and served wine but not food; its cli-entele was largely middle to upper class. The alehouse offered ale and beer, and sometimes simple food and lodging on the side. The alehouse was by far the most common sort of establishment, and the only one at which ordinary folk could be sure of a welcome. It was often recogniz-able by the

ale-stake

displayed over the door: either a pole with a bush attached at the end, or a broom, such as was used to sweep the yeast from the top during brewing—when a batch of ale was ready, the broom was set out to alert passersby. Many rural households opened temporary alehouses when a batch of ale came ready, although they could be fined if they failed to secure a license from the local justice of the peace.

An establishment that primarily served food was called an

ordinary,

so named because it served fixed fare at a standard price. According to the Swiss tourist Thomas Platter, women were as likely to frequent taverns and alehouses as men: one might even invite another man’s wife to such an establishment, in which case she would bring several other female friends and the husband would thank the other man for his courtesy afterward.

Many urban residents lacked full kitchen facilities, so they often purchased meals from one of these establishments, or bought “carry-out”

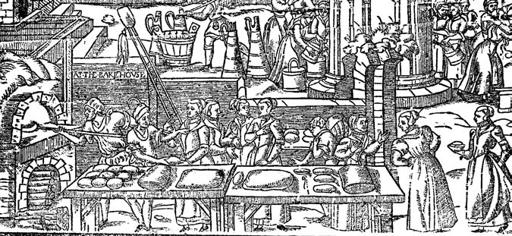

A bakehouse. [Besant]

176

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

from a baker, pie maker, or other food retailer. Even a household with a full kitchen might not have a bakeoven: some people would prepare the food at home, then bring it to a baker to be cooked.

RECIPES

The following recipes are all based on original sources: Gervase

Markham’s

The English Housewife,

first published in 1615; Thomas Dawson’s

The Good Huswifes Jewell

and

The Second Part of the Good Huswifes

Jewell,

first printed in the 1580s; and the anonymous

The Good Huswifes

Handmaide for the Kitchin

(ed. Stuart Peachey)

,

printed in 1594. In each case the original text is given in italics (with spelling modernized), followed by an interpretation for the modern cook.

Bread

Of baking manchets

[small loaves of fine flour]

.

First your meal, being ground upon the black stones if it be possible, which make the

whitest flour, and bolted through the finest bolting cloth, you shall put it into a clean kim-nel

[kneading trough],

and, opening the flour hollow in the midst, put into it of the best

ale barm the quantity of three pints to a bushel of meal, with some salt to season it with:

then put in your liquor reasonable warm and knead it very well together both with your

hands and through the brake

[a board with one end of a rolling pin hinged to it];

or for

want thereof, fold it in a cloth, and with your feet tread it a good space together, then, letting it lie an hour or thereabouts to swell, take it forth and mould it into manchets, round,

and flat; scotch about the waist to give it leave to rise, and prick it with your knife in the

top, and so put it into the oven, and bake it with a gentle heat. . . .

And thus . . . you may bake any bread leavened or unleavened whatsoever, whether it

be simple corn, as wheat or rye of itself, or compound grain as wheat and rye, or wheat

and barley, or rye and barley, or any other mixed white corn; only, because rye is a little

stronger than wheat, it shall be good for you to put to your water a little hotter than you

did to your wheat.

[Markham, chap. 9, nos. 15–17]

Sift

3 cups unbleached flour;

use white flour for manchets, whole wheat for a household loaf, or any combination of wheat, rye, and barley as Markham suggests. Dissolve

1 teaspoon active dry yeast

in

1 cup lukewarm water or beer

and stir in

1 teaspoon salt.

Make a well in the flour and pour the yeast mixture into it. Mix and knead for 5 minutes. Since the wheat can vary in initial moisture, you might have to add water or flour to ensure that it is moist to the touch but not sticky. Let the dough rise in a warm place for about an hour. The loaf should be round and flat, and pricked on top with a knife. Let it rise until it has doubled in volume, about 45 minutes to an hour. Preheat the oven to 500 degrees F. When the dough has risen, put it in the oven and reduce heat to 350 degrees F. After about 20 minutes the bread should be golden brown and ready to remove from the oven.

Food and Drink

177

Pottage

To make the best ordinary pottage, you shall take a rack of mutton cut into pieces, or a leg of

mutton cut into pieces; for this meat and these joints are the best, although any other joint

or any fresh beef will likewise make good pottage: and, having washed your meat well, put it

into a clean pot with fair water, & set it on the fire; then take violet leaves, endive, succory

[a salad herb, closely related to endive],

strawberry leaves, spinach, langdebeef

[oxtongue],

marigold flowers, scallions, and a little parsley, and chop them very small together; then take

half so much oatmeal well beaten as there is herbs, and mix it with the herbs, and chop all

very well together: then when the pot is ready to boil, scum it very well, and then put in your

herbs, and so let it boil with a quick fire, stirring the meat oft in the pot, till the meat be boiled

enough, and then the herbs and water are mixed together without any separation, which will

be after the consumption of more than a third part: then season them with salt, and serve

them up with the meat either with sippets

[a small slice of bread, toasted or fried, used to sop up gravy or broth]

or without.

[Markham, chap. 2, no. 74]

Cut

1½ lb. mutton

into 1-inch cubes. Add

6 cups water.

Bring to a boil.

Chop together

1 cup endive, 1½ cup spinach, 1½ cup scallions, 1 cup

parsley,

and

2 cups rolled oats

(if you can find yourself the violet leaves, succory, strawberry leaves, oxtongue, and marigold flowers, then so much the better). Stir the herbs and oatmeal into the liquid, cover and simmer gently for about 1 hour or until meat is tender, stirring periodically. Add

salt

to taste. Makes 4–6 servings.

This dish is fairly representative of the ordinary fare of the Elizabethan commoner, relying on mutton and domestically grown grain and herbs.

Roast Chicken

Preheat oven to 450 degrees F. Clean one 4–5 lb. chicken or capon. Stuff with 1 recipe stuffing (see below), truss up the legs, and sew the body cav-ity shut. Place the bird on a roasting pan in the oven and reduce temperature to 350 degrees F. Baste frequently with the juices from the bird; you may begin the process by basting with 2 teaspoons salt dissolved in 1 cup water. Roast for about 20 minutes a pound (the bird will be done when its juices run clear and there is no redness left in the meat). Pour 1 recipe capon sauce (see below) on the bird just before serving.

Stuffing

To farse all things. Take a good handful of thyme, hyssop, parsley, and three or four yolks of

eggs hard roasted, and chop them with herbs small, then take white bread grated and raw

eggs with sweet butter, a few small raisins, or barberries, seasoning it with pepper, cloves,

mace, cinnamon, and ginger, working it all together as paste, and then may you stuff with

it what you will.

[Dawson,

The second part,

p. 10]

Take the yolk of

1 hard-boiled egg,

and chop it up with

½ teaspoon

thyme

and

2 tablespoons parsley.

Work together in a bowl with

2 cups

178

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

bread crumbs, 2 raw eggs, 2 tablespoons unsalted butter, 2 tablespoons

raisins, ⅛ teaspoon pepper, ⅛ teaspoon cloves, ⅛ teaspoon mace, ⅛ teaspoon cinnamon,

and

¼ teaspoon ground ginger.

Capon Sauce

To make an excellent sauce for a roast capon, you shall take onions, and, having sliced

and peeled them, boil them in fair water with pepper, salt, and a few bread crumbs: then

put unto it a spoonful or two of claret wine, the juice of an orange, and three or four slices

of a lemon peel; all these shred together, and so pour it upon the capon being broke up.

[Markham, chap. 2, no. 79]

Peel and dice

1 small onion.

Add to

1¾ cups boiling water,

along with

¼ teaspoon pepper, ½ cup bread crumbs,

and

salt

to taste. Boil for 5 minutes, then remove from heat, and add

1 tablespoon red wine, 3 tablespoons freshly squeezed orange juice,

and

1 teaspoon grated lemon

rind.

Pour it on the roast and serve.

Salads and Vegetables

Your simple sallats are chibols

[wild onion]

peeled, washed clean, and half of the green

tops cut clean away, so served on a fruit dish; or chives, scallions, radish roots, boiled carrots, skirrets

[a species of water parsnip],

and turnips, with such like served up simply;

also, all young lettuce, cabbage lettuce, purslane

[the herb Pastalaca oleracea],

and divers other herbs which may be served simply without anything but a little vinegar, salad oil

and sugar; onions boiled, and stripped from their rind and served up with vinegar, oil and

pepper is a good simple salad; so is samphire

[the herb Crithmum maritimum],

bean

cods, asparagus, and cucumbers, served in likewise with oil, vinegar, and pepper, with a

world of others, too tedious to nominate. Your compound salads are first young buds and

knots of all manner of wholesome herbs at their first springing, as red sage, mints, lettuce,

violets, marigolds, spinach, and many other mixed together, and then served up to the table

with vinegar, salad oil and sugar.

[Markham, chap. 2, no. 11]

The term

salad

as used by Markham covers a range of vegetable dishes.

His description suggests several possibilities, of which two are offered here.

(1) Chop

3 carrots, 2 parsnips,

and

1 turnip

into 1-inch cubes. Bring

4 cups water

to a brisk boil and add the chopped vegetables. Chop together

1 tablespoon chives, 2 radishes,

and

1 tablespoon scallions.

When the vegetables are tender, drain them, mix them with the chives, radishes, and scallions, and serve.

(2) Wash and tear up

½ head leaf lettuce

and an

equal quantity of spinach.

Add

3 tablespoons mint leaves

and, if possible,

3 tablespoons violets

and

3 tablespoons marigolds.

Mix

3 tablespoons olive oil

and

3 tablespoons vinegar

with

½ teaspoon sugar

to make a salad dressing. This salad can be varied with the addition of

sliced cucumber, endive, radishes, spin-Food and Drink