Daily Life in Elizabethan England (34 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

dish was the pie, which might stuffed with meat, poultry, fish, shellfish, fruit, or vegetables. The crust or

coffin

was often a heavy paste that served merely to seal up the food—it was not actually eaten.

Cooking utensils were typically made of clay, iron, copper, or brass.

Because copper and its alloys (such as bronze and brass) are less susceptible than iron to rust and can transmit heat very quickly, they are good for heating water. Iron, on the other hand, transmits heat more slowly but spreads it more evenly, and after long use, it acquires an oily coating that keeps food from sticking to it. For these reasons, iron was the better material for cooking food. Clay pots were also useful for cooking, since they could be placed very close to the fire and conduct heat quite evenly.

A well-appointed kitchen would also have a wooden kneading-trough

for making bread and a mortar and pestle for grinding. To protect the flour from vermin, it was kept in legged wooden bins called

meal arks.

Spices and dried fruits might be stored in small boxes or clay pots; vinegar, oil, and other liquids in leather, earthenware, or glass bottles. Additional storage was provided by baskets and linen and canvas bags and sacks. Spices were normally stored whole, to be ground as needed. Salt was kept in special salt boxes. The kitchen would be provided with cupboards and shelves for storing all of these utensils and provisions.

DRINKS

Water was not a particularly healthy drink in Elizabethan England due to poor sanitation in the cities and natural impurities in country water.

Under the circumstances, fermented drinks were actually the healthier

170

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

choice, since the brewing process and alcoholic content tended to inhibit bacteria. The traditional English beverage was ale, made of water, malted barley, herbs and spices; it lacked hops, so it tasted little like what we call ale today, and its shelf life was short. The closest modern equivalents in flavor are the spiced ales of Belgium and northern France. Beer—similar to ale but brewed with hops—had come to be favored in the cities. Beer was lighter and clearer than ale; the hops also made it keep longer, which made it cheaper. The best beer was one to two years old, but usually it was consumed after just a month of aging.

Ale varied greatly in strength, from the watery small ales to

double ale,

or even the rather expensive

double-double,

sometimes known by such evocative names as Mad Dog, Huffcap, Father Whoreson, and Dragons’ Milk.

Ale was the staple drink of Elizabethan England, having nutritional properties as well as being a source of water for the body. As a daily staple it was generally consumed in forms with very low alcohol content: children drank it as well as adults, and people would drink it when they breakfasted and throughout the working day. A gallon a day seems to have been a normal ration for a grown man.

Wine in Elizabethan England was invariably imported, since English grapes were unsuitable for winemaking. What the Elizabethans called French wine came from the north of France; wines from southern France, such as the modern Bordeaux, were known to the Elizabethans as Gas-con wine or

claret.

Rhenish wines, both red and white, were also enjoyed in England; other wines came from Italy and even Greece. The favorite imports appear to have been the sweet fortified wines of the Iberian pen-insula, especially

sack,

imported from Jerez (whence its modern name,

sherry

), and

madeira

and

canary,

respectively, from the Madeira and Canary Islands off the northwest coast of Africa. The English liked their wines sweet and would often sugar them heavily. Because it was imported, wine was quite expensive—typically 12 times the cost of ale—so it was primarily a drink for the privileged. For reasons of health (and perhaps expense), many people would add water to their wine.

Although English grapes were not used for winemaking, other English fruits yielded a range of alternative drinks. These included cider from apples, perry from pears, and

raspie

from raspberries. Other fruits used in winemaking included gooseberries, cherries, blackberries, and elderberries.

Mead and metheglin, made with honey, were common in Wales and were also known in England. Distilled liquors were also in use, albeit mostly for medicinal purposes: the commonest was known as aqua vitae. There were also mixed drinks, notably posset, an ale drink vaguely comparable to egg-nog, and syllabub, a similar concoction soured with cider or vinegar. Both wine and beer might be seasoned with herbs and spices—spiced wine was often called

hippocras.

Milk was not normally consumed plain, but whey, the watery part of milk that remains after coagulated curds are removed, was sometimes drunk by children, the poor, and the infirm.

Food and Drink

171

The Elizabethans closely associated drink with tobacco, which was

served along with beer in alehouses. In fact, it was common to speak of

drinking

tobacco smoke. Tobacco was first brought to England from the New World during Elizabeth’s reign, and it quickly became widely popular. Some, like King James of Scotland (soon to be king of England as well), reviled the new weed, but most authorities believed it had great medicinal powers. In the words of one contemporary author, “Our age has discovered nothing from the New World which will be numbered among the

remedies more valuable and efficacious than this plant for sores, wounds, affections of the throat and chest, and the fever of the plague.”2

Elizabethan tobacco was considerably stronger and more narcotic than modern commercial versions. A Swiss visitor to England in 1599 was struck by the English fondness for the tobacco-pipe:

The habit is so common with them, that they always carry the instrument on them, and light up on all occasions, at the play, in the taverns or elsewhere, drinking as well as smoking together, as we sit over wine, and it makes them riotous and merry, and rather drowsy, just as if they were drunk, though the effect soon passes.

And they use it so abundantly because of the pleasure it gives, that their preachers cry out on them for their self-destruction, and I am told the inside of one man’s veins after death was found to be covered in soot just like a chimney.3

TABLEWARE

In the Middle Ages the dining table had most often been a temporary board set upon trestles, but by the late 16th century the trestle table had generally been supplanted by the permanent

table dormant.

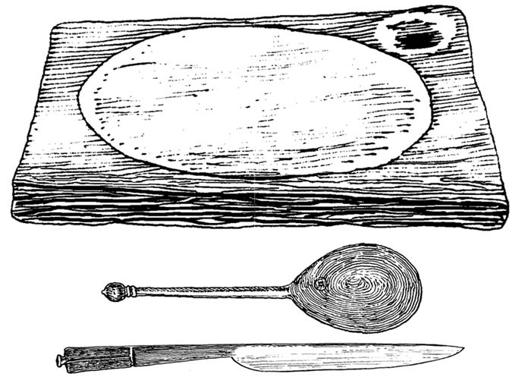

At mealtimes this table was covered with a white linen tablecloth. A typical place setting consisted of a drinking vessel, a knife and spoon, a trencher (wooden plate), a bowl, and a linen napkin.

Elizabethan drinking vessels were quite varied. Some were plain beakers of ceramic, horn, or pewter; others were fine goblets of glass, silver, or gold. Very poor folk might drink from a wooden bowl (a custom observed by many at Christmastime when drinking the wassail, or spiced ale). One of the most distinctive Elizabethan drinking vessels was the

black jack,

a mug made of leather and sealed with pitch. Drinks were poured from jugs, which were made of the same range of materials as the drinking vessels themselves. The jug might sit in a vat of water to keep the drink cool.

The least expensive spoons were made of horn or wood; finer spoons were cast in metals such as pewter or silver. The characteristic spoon of the period had a thin handle, round in cross-section, and a large fig-shaped bowl. The handle of a metal spoon sometimes had a decorative ending called a

knop.

Designs for knops included various sorts of balls, acorns, and even human figures: one form was the Apostle Spoon, which had a knop in the figure of one of the Twelve Apostles. Pewter and silver spoons

172

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

A SERVANT’S DUTIES AT TABLE

When your master will go to his meat, take a towel about your neck, then take a cupboard cloth, a basin, ewer, and a towel, to array your cupboard; cover your table, set on bread, salt, and trenchers, the salt before the bread, and trenchers before the salt. Set your napkins and spoons on the cupboard ready, and lay every man a trencher, a napkin, and a spoon. . . . See ye have voider [clearing-platter] ready for to avoid [remove] the morsels that they do leave on their trenchers. Then with your trencher knife take off such fragments and put them in your voider, and set them down clean again. All your sovereign’s trenchers or bread, void them once or twice, especially when they are wet, or give them clean.

Hugh Rhodes,

The Book of Nurture

[1577], in

The Babees Book,

ed. F. J. Furnivall (London: Trübner, 1868), 66–67.

were among the commonest luxuries in ordinary households and were

frequently given as gifts at weddings and christenings.

The ordinary form of plate was the trencher, a square piece of wood with a large depression hollowed out for the food and a smaller one in the upper right-hand corner for salt; fancier round plates might be made of pewter or silver. The trencher was smaller than a modern dinner plate, more like a modern salad plate. Ordinary bowls were made of wood or ceramic. In addition to the plates for the diners, empty plates called

voiders

were often set out to receive bones, shells, and other scraps.

Missing from the typical place setting was the fork, which was not a feature of the Elizabethan table at all. The Italians were using forks in this period, but in England, the fork was exclusively a kitchen utensil. Food was cut on either the cook’s bench or the serving platter, so by the time the food hit the trencher, it did not need to be held down and cut.

In some cases, diners would provide their own knives, since many people carried these as part of their ordinary attire. The Elizabethan knife was invariably pointed—the blunt form of modern table knives was introduced during the 17th century to reduce the danger of mealtime brawling.

The blade was of carbon steel; unlike modern stainless steels, it had to be kept dry and oiled to prevent rust. The handle might be of wood, horn, bone, or ivory.

Salt was put out in saltcellars, and the diners transferred it with their knives to the salt-depression on the trencher. Silver saltcellars were a common luxury, pewter being a cheaper alternative. Condiments (such as mustard) and sauces were also set out for the diners. Valuable tableware was one of the likeliest luxuries for a person to own, as it could be brought

Food and Drink

173

A trencher, knife, and pewter spoon. [Hoornstra/Forgeng]

out to impress guests: a poor man might well invest in some pewter, and a man of limited means might own some silver or glass.

ETIQUETTE

Eating and drinking are among the most ritualized aspects of daily life, and this was as true in Elizabethan England as in other societies. It was customary to begin the meal by washing hands—a particularly important ritual in an age when people used their fingers in eating much more than we do today. This generally involved one of the servants or children passing among the guests with a pitcher of water, a basin, and a towel. When everyone had washed, someone would recite a prayer, after which the meal would begin.

Adult men generally kept their hats on at the table, unless one of their fellow diners was clearly higher in social status; women wore their coifs, while boys and menservants were bareheaded out of respect for their superiors. In large and wealthy households there might be a substantial number of servants to bring the food to the table and clear it away, as well to pour drinks when they were called for. In the best households, drinks

174

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

MEALTIME PRAYERS FROM A DEVOTIONAL BOOK OF 1566

A Prayer to Be Said before Meat

All things depend upon thy providence, O Lord, to receive at thy hands due sustenance in time convenient. Thou givest to them, and they gather it: thou openest thy hand, and they are satisfied with all good things.

O heavenly Father, which art the fountain and full treasure of all goodness, we beseech thee to shew thy mercies upon us thy children, and sanctify these gifts which we receive of thy merciful liberality, granting us grace to use them soberly and purely, according to thy blessed will: so that hereby we may acknowledge thee to be the author and giver of all good things, and above all that we may remember continually to seek the spiritual food of thy word, wherewith our souls may be nourished everlastingly, through our Saviour Christ, who is the true bread of life, which came down from heaven, of whom whosoever eateth shall live for ever, and reign with Him in glory, world without end. So be it.

A Thanksgiving after Meals

Glory, praise, and honour be unto thee, most merciful and omnipotent Father, who of thine infinite goodness hast created man to thine own image and similitude; who also hast fed and daily feedest of thy most bountiful hand all living creatures: grant unto us, that as thou hast nourished these our mortal bodies with corporal food, so thou wouldest replenish our souls with the perfect knowledge of the lively word of thy beloved Son Jesus Christ; to whom be praise, glory, and honour, for ever. So be it.