Daily Life in Elizabethan England (38 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

190

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

The actor Will Kemp morris-dancing to the pipe and tabor. [

Shakespeare’s

England

]

sometimes for foxes or hares. Modern greyhound racing had its origins in hare hunting, in which a pair of dogs would be set loose after a hare, and wagers were laid on which one would catch the quarry. Birds were also hunted, in two different ways. One was the ancient and difficult sport of falconry in which trained falcons were sent after the prey. The alternative involved crossbows or, increasingly, firearms. Rather more sedate was fishing, enjoyed by many who found hunting too barbarous or expensive. All these sports might be enjoyed by women as well as men. Ordinary people did not generally hunt or fish for sport. Indeed, they were not allowed to do so. The rights of hunting and fishing were normally reserved for landowners, although poaching was still common as a means of obtaining extra food.

Hunting was a mild pastime in comparison with some Elizabethan

animal sports, especially bullbaiting, bearbaiting, and cockfighting. Cockfighting involved pitting roosters against each other in a

cockpit,

a small round arena surrounded by benches—sometimes a permanent structure

was built for the purpose. In bullbaiting, a bull was chained in the middle of a large arena and set upon by one or more mastiffs. The dogs were trained to clamp their jaws closed on the bull’s nose or ears and hang on

Entertainments 191

until the bull fell down exhausted; the bull meanwhile tried to shake the dogs free and gore them to death. Bearbaiting was very similar, with the bull replaced by a bear. In all of these sports, the onlookers would place wagers on the outcome of the combat. Bullbaiting usually ended in the death of the animal: when an old bull was to be butchered, it was common practice to bait the animal to make its meat more tender. Bearbaiting was usually more fatal to the dogs, as the bears were expensive and the sport was weighted in their favor—in fact, several bears became entertainment stars in their own right, known to Londoners by names like George Stone, Harry Hunks, and Sackerson. These entertainments, brutal though they seem to modern sensibilities, were widely enjoyed—even Elizabeth liked to attend bearbaitings. The main voice of criticism was from Puritan com-mentators like Philip Stubbes: “What Christian heart can take pleasure to see one poor beast to rend, tear, and kill another, and all for his foolish pleasure? . . . For notwithstanding that they be evil to us, and thirst after our blood, yet are they good creatures in their own nature and kind, and made to set forth the glory, power, and magnificence of our God . . . and therefore for his sake we ought not to abuse them.”4

Some animal-related activities were not so violent. Horse racing was increasing in popularity—England’s first formal racecourses were built during the 1500s. Animals were also kept as pets. Dogs and cats were usually working members of the household, serving for home protection and rodent control, but upper-class households sometimes kept lapdogs, birds, or even monkeys as pets.

MARTIAL SPORTS

The violence of Elizabethan animal sports had parallels in human combat games. The aristocracy sometimes practiced the medieval sport of the tournament, a colorful but expensive pastime that typically served as the centerpiece of a major public festival. Featured activities might include jousting, pitting one horseman against another at lancepoint, or foot combat with swords or spears. Participants used blunt weapons and specialized tournament armor that maximized protection, and the combatants were usually separated by a wooden barrier that further reduced the level of risk.

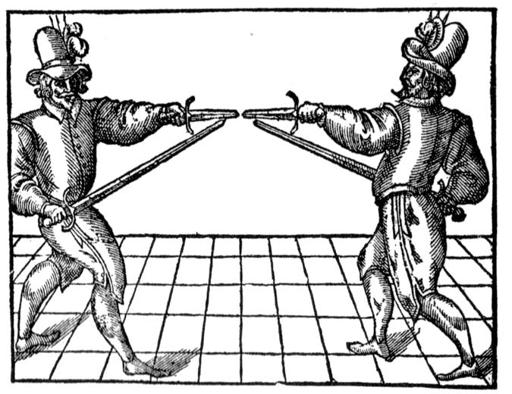

Fencing was popular both as a spectator entertainment and a participa-tory sport. Fencing weapons had blunted edges and rounded tips but the sport was dangerous nonetheless. The rapier used in fencing was a great deal heavier than a modern fencing weapon; the only protective gear was a padded doublet, and occasionally a large round button secured over the tip of the blade to reduce the risk of putting out an eye. Even so, the risk of personal injury, even death, was always present, and public fencing matches were often played to first blood—the winner was the first one who could draw blood from his opponent.

192

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Fencers with sword and dagger. [Castle]

Sometimes the rapier was supplemented by a small round shield, called a

buckler,

or by a larger one, either round or square, called a

target.

Alternatively, the fencer might use a rapier in one hand and a dagger in the other, or even two rapiers.

The rapier was considered an Italian weapon; those who preferred English traditions might fight with a backsword instead. Where the rapier was purely a civilian weapon, the backsword was designed to be suitable for military use. It was typically shorter than the rapier, with a thicker blade, optimized for cutting blows instead of thrusts with the point. Sometimes the combatants used wooden swords called wasters or cudgels. Other weapons used by fencers included quarterstaves, pikes, two-handed

swords, and halberds. Somewhat less fashionable was wrestling, which had traditionally been a skill of the medieval knightly class, but was now increasingly seen as an entertainment of country folk.

Such martial arts had some practical application. There was a certain amount of lawlessness in Elizabethan England: even in London, street fights and brawls were known to break out in broad daylight. For many people, the ability to defend oneself was an important life skill.

Other martial sports were geared toward military rather than civilian purposes. By law, every English commoner was required to practice archery regularly. The law was originally introduced in the 1300s, when

Entertainments 193

archery was still very important on the battlefield. By Elizabeth’s time archery had declined in military significance, but Elizabeth encouraged it nonetheless (she sometimes engaged in the sport herself, as did many English aristocrats). There were archers in the militia, and some military theorists still preferred the bow to the gun. Laws promoting archery were not strictly observed, but the sport remained popular among all classes and was widely seen as an especially patriotic pastime.

More useful for the national defense was the practice of military drill with pike and shot. Elizabeth’s government made a concerted effort to improve England’s defenses by training a national militia known as the Trained Bands. Sixteenth-century warfare involved more training of the ordinary soldier than had once been the case. The matchlock musket required less physical strength and skill than the bow, but it was a fairly complex weapon to fire, requiring 20 to 30 seconds for each shot and some two dozen distinct motions—all of this while holding a slowly burning length of saltpeter-impregnated rope (called the

match

) and charging the weapon with gunpowder. An error could be fatal.

The pike, a 16-to 24-foot spear designed to ward off cavalry, was less dangerous to its user but even more demanding. There were about a dozen positions in which the pike might be held, and the pikemen had to learn to move from each position to all the others in precise coordination with the rest of the pikemen—in a tight block of pikeman, every weapon had to be aligned with all the others to avoid entanglement. The government’s efforts to promote military training met with extraordinary success, for military drill actually became a fashionable pastime, as well as a popular spectator entertainment.

PHYSICAL GAMES

A tendency toward violence can be seen even in some of the nonmar—

tial pastimes of the Elizabethans. The most characteristic English outdoor game of the period was football, especially favored by the lower classes.

Elizabethan football was rough, loud, and perilous to bystanders as well as players. The game was roughly the same as modern European football (soccer in America), but with fewer rules. Two teams would try to kick a ball through their opponents’ goal. The ball was made of a farm animal’s bladder, inflated, tied shut, and sewn into a leather covering. A major part of the game was the subtle art of tripping up one’s opponents on the run.

Richard Mulcaster, a London schoolteacher who believed that the game

“had great helps, both to health and strength,” acknowledged that “as it is now commonly used, with thronging of a rude multitude, with bursting of shins, and breaking of legs, it be neither civil, neither worthy the name of any train to health,” but he argued that the game could be made safer by the use of a referee, assigned positions for the players, and rules about the permissible levels of physical contact.5 Even more violent were the

194

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

PHILIP STUBBES ON FOOTBALL

Football playing . . . may rather becalled a friendly kind of fight than a play or recreation, a bloody and murdering practice, than a fellowly sport or pastime. For doth not everyone lie in wait for his adversary, seeking to overthrow him, and to pitch him on his nose, though it be upon hard stones, in ditch or dale, in valley or hill, or what place so ever it be, he careth not, so he may have him down? And he that can serve the most of this fashion, he is counted the only fellow, and who but he? . . . They have slights to meet one betwixt two, to dash him against the heart with their elbows, to hit him under the short ribs, with the gripped fist, and with their knees, to catch him upon the hip, and to pitch him on his neck, with an hundred such murdering devises. And hereof groweth envy, malice, rancor . . . and sometimes fighting, brawling . . . homicide and great effusion of blood.

Phillip Stubbes,

The Anatomy of Abuses

(London: Richard Jones, 1583), 120r-v.

versions known as

camp-ball

in England,

hurling

in Cornwall, or

cnapan

in Wales. In these games, a ball or other object was conveyed over open country to opposing goals by any means possible—even horsemen might be involved. These games frequently led to serious injuries.

Similar to football in concept if not equipment was the game of bandy-ball, the ancestor of modern field hockey. The object of the game was to drive a small, hard ball through the opponents’ goal with hooked clubs (almost identical to field hockey sticks).

Bat-and-ball games were known, but are poorly attested in Elizabethan sources. Stoolball in later years would be a game similar to cricket, with the ball thrown at a stool and a batsman trying to fend it off, but the earliest description of the game does not mention a bat (see the end of this chapter for an interpretation). Stoolball was one of few sports played by women as well as men. It is often confused with Stowball, a game played in Wiltshire and adjoining counties—a distant relative of croquet, in which one team tried to bat the ball around the course, while the other team would try to hit it back. A family of bat games were played with a

cat,

a cylinder of wood tapered at both ends so that the batsman could strike it on the ground, making it fly up in the air for him to swing at. In the game of trap or trapball a levered device was used to achieve the same effect.

Tennis, a game introduced from France during the Middle Ages, called for expensive equipment and an equally expensive court, so it was played only by the rich. The tennis ball was made of woolen scraps tightly wrapped in packing thread and encased in white fabric; the rackets were made of wood and gut. The game was played on a purpose-built, enclosed court with a complex shape—the Elizabethan game survives today under the name

real tennis.

Tennis was one of the most athletic games played by