Daily Life in Elizabethan England (5 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

THE RURAL COMMUNITY

Below the gentry in the manorial hierarchy were the landholding commoners. Land could be held in various ways, deriving from the customs of the medieval manor. The most secure form of tenancy was the freehold.

Freeholders held their lands in perpetuity: their holdings were passed from generation to generation with no change in terms. The rent charged for freehold lands had been fixed in the Middle Ages, and inflation had rendered the real cost of these holdings minimal. Few manor lords even bothered to collect freehold rents, and they consequently fell out of use: a freeholder was the effective owner of his landholding.

Less secure than a freeholding was leasehold land. Leasehold tenancies were for fixed periods, sometimes a lifetime or more—for example, for the life of the leaseholder, his wife, and his son—sometimes as little as a year. Leasehold land might be manorial demesne land, rented out by the manor lord as a source of cash, but villagers often leased to each other, sometimes subletting their own leaseholds. When a lease ended, it was subject to renegotiation. Manor lords often simply renewed the existing lease for the lessor, or for the heir in the case of a lifetime lease. But the end of a lease offered an opportunity for an ambitious landlord: he might take the land back into his own hands as part of his estate management strategy, or insist on a higher rent.

The heirs of medieval serfs were the copyholders, also called customary tenants. A copyhold was a landholding that had once been held under villeinage tenure. At the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign, there were actually a few hundred villeins in the country, but villeinage was rapidly dying out,

Society 15

and had all but vanished by 1600. Although the copyholder was no longer in a state of personal servitude, copyhold tenure could be precarious. The terms of a copyhold were dictated by custom—the holder was supposed to have a copy of the manorial records that confirmed the right to the holding, but many essential features of the holding were never committed to writing. The rent, fees, and ancillary rights associated with the holding might be based purely on unwritten tradition, and it could be hard to prove which customs carried legal force and which did not.

In principle, a copyhold was a perpetual right that was passed on in the family like other heritable property, although the heir had to pay an entry fee at the beginning of the tenancy. However, when the copyhold changed hands, the landlord might try to raise the entry fee or the rent—sometimes with the deliberate intent of driving the heir out of the landholding. When conflicts arose, the tenant had no recourse to the Common Law courts, which had no jurisdiction over copyhold tenure. The matter might be brought before an Equity court, but the tenant still needed the resolve and the money to prosecute a case. In general, landlords were finding ways to replace copyhold tenancies with leaseholds, allowing them more flexibil-ity in managing their estates.

For all forms of tenure, the land itself might be only a part of the rights associated with the holding. Villages typically had uncultivated areas of

commons

such as pasture and woodlands, shared collectively by the residents. A landholding often came with rights of commons: these might a quota of firewood from the woods; pasturage for a certain number of livestock; grazing animals on the village fields at certain times of year; or gathering leftovers from the fields after harvest—a custom called

gleaning

that was a significant source of food for the poorest villagers.

Tenants found themselves under increasing pressure in an age of inflation when many manor lords were looking to increase the yields from their lands. The simplest way was to raise fees and rents. Contemporaries called this

rack-renting,

and traditionalists saw it as exploitative, at least if the increase was excessive—naturally, landlords and tenants often disagreed on what was excessive.

Rack-renting could also be used to drive tenants out of their holdings.

For many manor lords, the way to increase income was higher productivity. This often meant consolidating large blocks of agricultural land for greater efficiency or to implement improved farming techniques. By fair means or foul, many landowners were finding ways to build up consolidated farmlands, enclosing them with hedges to set them apart from the lands held by others. This process of

enclosure

might also incorporate common pastures and woodlands, converting them to farmland to increase their value. Not only did enclosures provoke hostility when tenants were driven out of their holdings by unscrupulous tactics, but the enclosed land was no longer accessible for traditional rights of commons.

Many saw enclosure as a violation of sanctioned custom, and for some it

16

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

constituted a real threat to a livelihood that might be precariously balanced on the rights of commons. In 1601, tenants of Sir Miles Sandys of Willingham (Cambridgeshire) raised a joint fund to challenge at law his efforts to enclose common and fen lands; the following year a number of them broke into a meadow he had enclosed, pasturing cattle there in an act of symbolic protest—the conflict was ultimately settled by arbitration.3

This does not mean that all tenants were in constant danger of home-lessness or impoverishment. Not all landlords were inclined to raise rents or evict tenants. They too had a vested interest in tradition and social stability, and many were reluctant to engage in behavior that could disrupt the social system. On the other side of the equation, many of the wealthier villagers were themselves buying up or trading landholdings to enclose them for purposes similar to those of the manor lords.

How a villager felt about enclosure might depend less on the terms of his holding and more on its size. These two were independent of each other, although the larger holdings were more likely to be freeholds, and the smaller ones leaseholds or copyholds.

The wealthiest villagers were known as yeomen. Traditionally, the title was supposed to apply to freeholders whose lands yielded revenues of at least 40 shillings a year, a qualification that entitled the holder to vote in Parliamentary elections. In reality, the 40s. qualification was outdated—

one contemporary estimated that £6 would be a more realistic minimum—

and in practice a leaseholder might also be considered a yeoman if he held enough land. Roughly speaking, the yeomen were landholders who held something on the order of 50 acres or more. At this level they could reliably ride out the tumultuous waves of the Tudor economy and sustain or increase their wealth. Overall, this class probably accounted for around 10

percent of the population. A yeoman’s income might amount to dozens of pounds a year, and the wealthier among them had incomes equivalent to the gentry. The yeoman was a dominant figure in village society, and was often called on to serve in such positions as village constable or parish churchwarden.

Tenants whose holdings were smaller but still sufficient to sustain a family were known as husbandmen—a term also used more generally of anyone who worked his own landholding, more or less equivalent to the modern “farmer.” A typical husbandman’s landholding might be around 30 acres, yielding a normal annual income around £15, enough to maintain his family comfortably under normal circumstances, but potentially at risk in the inflationary and uneven economic environment of the period.

Husbandmen may have accounted for about 30 percent of England’s population.

The smallest landholders were called cottagers. A cottager might hold no more than the cottage his family lived in and the acre or two on which it sat. A few had some land in the village fields as well, occasionally as much as 10 or 15 acres. A cottager’s holding was too small to support a

Society 17

household, so cottagers had to supplement their income by hiring themselves out as laborers. Most did agricultural work, but depending on local opportunities, there might be other options: metalworking (especially making small wares like nails or knives), weaving, pottery, charcoal burning, and mining, were all common sources of income for a rural cottager and would eventually lead to urbanization of some of these rural communities during the Industrial Revolution.

At the very base of the rural hierarchy were the servants and laborers who had no homes of their own and were entirely dependent on others for both lodging and livelihood. Such people may have represented a quarter to a third of the rural population. Servants were common in landholding households at all levels, particularly if the family lacked children of an age to help out with farmwork. Gentry households might have specialized domestic servants, but most rural servants were general workers hired on an annual basis, living in the home and helping out with the daily male or female work of the farm—looking after livestock, tending to the dairying, and helping to cultivate the fields.

Laborers did similar kinds of work, but on a more short-term basis. They might be local cottagers, or they might be itinerant workers traveling from village to village in search of work. The life of such traveling workers was precarious. It was technically illegal for them to leave their home parish without permission from an employer or a local authority, and those who had trouble finding employment could easily find themselves falling into poverty, vagrancy, or crime. Many ended up migrating to a town in search of work.

THE URBAN COMMUNITY

The constant influx of labor from the countryside was essential to the life of the Elizabethan town. Urban living conditions were crowded and unsanitary, and deaths outpaced births. Immigration from the countryside allowed towns not only to maintain their numbers, but to grow substantially over the course of Elizabeth’s reign. The fastest expansion was in London, which grew from an estimated 120,000 inhabitants in 1558 to over 200,000 by 1603, overtaking Venice as the third largest city in Europe, after Paris and Naples. Such a rate of growth required an influx of some 3,750 immigrants a year by the end of Elizabeth’s reign. London dominated English society to a degree not generally true of other European capitals: about 1 Englishman in 20 lived in London, and few people in the country would be without a friend or relative who lived in London.

Other towns were growing, but none was on the same scale. The second tier of English cities consisted of Norwich, Bristol, and York, with about 10,000–12,000 in 1558 and 15,000 in 1603. Only a handful of other towns, including Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Salisbury, Exeter, and Coventry, had as many as 10,000 inhabitants by 1600. Historians sometimes refer to these

18

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

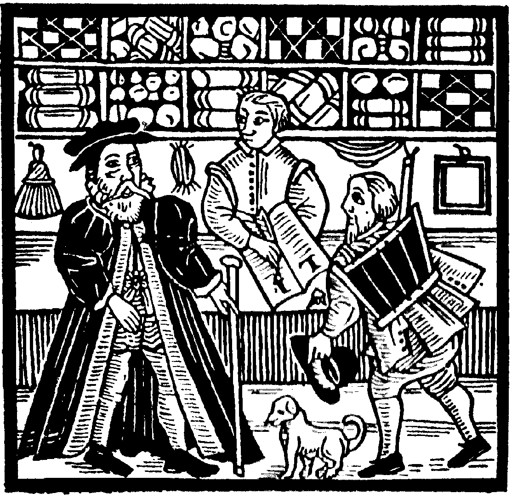

Interior of a shop. [Hindley]

cities as provincial capitals: they acted as hubs in the political and economic life of their respective sections of the country.

Below these were about 100 towns that constituted a significant presence in their counties: these county centers typically had populations of 1,500 to 7,000, with complex street layouts and city walls, multiple markets in the course of a week, and annual fairs. The smallest urban centers were the 700

or so local market towns, having populations of no more than 1,000–2,000, and often fewer, with limited urban features beyond their weekly market.

Most of the boroughs that sent representatives to parliament fell into this last category. Overall, only about 10 percent of the population lived in towns of 1,000 or more by the end of Elizabeth’s reign.

Although towns varied hugely in size, they shared a number of features in common. Most held charters that gave them a measure of self-government, including the right to choose their governing officers, establish local by-laws, hold courts to settle civil and petty criminal cases, and to hold and regulate markets. Land in the towns was normally held by burgage tenure, a less restrictive form of land ownership that allowed the property to be freely bought and sold.

Towns often played a role as focal points in the network of royal and church administration: sheriffs and royal courts worked from the major

Society 19

town in a shire, and the larger towns might be home to a bishop’s cathe-dral or the seat of an archdeacon. However, the town’s own government and social structure operated independently of these authorities.

At the heart of urban government was the concept of town citizenship, usually termed

freedom

of the town. A town’s citizens, also called freemen or burgesses, were those who enjoyed the full privileges of belonging to the town. These typically included the right to trade freely and some degree of participation in the town’s government. Many towns had some sort of deliberative or legislative body in which freemen were involved. A freeman might also hold civic office, for example serving on a court or as a constable. As a self-governing polity, a town relied on its citizenry to staff the largely unpaid posts in town government, and perhaps one freeman in four or five held some office at any given time. However, real political power typically lay in the hands of an oligarchy drawn from the most wealthy and influential citizens.