Daily Life in Elizabethan England (7 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

might advance in society if she managed to marry a man of significantly higher social station. Meanwhile, a gentleman who acquired excessive debts might slide down the social scale, and enclosure in the countryside could leave a rural landholder without a livelihood.

The growth of education as a route to gentlemanly status also opened up opportunities for social advancement and obscured the distinction between gentleman and commoner. London in particular was a venue

where someone with education, polish, and enough money to afford a good set of clothing might pass himself off as a gentleman, and perhaps even win a lasting place in the gentlemanly class. The life story of William Shakespeare is emblematic: born in 1564 as the son of a glover in the provincial market-town of Stratford-on-Avon, his success in London’s burgeoning entertainment industry allowed him to return in later years to his home town as a major local landowner and gentleman with his own coat of arms.

While the official social vocabulary was couched in traditional terms of hierarchy and status, much of a person’s standing actually depended on a more fluid social asset known as

credit

. Credit reflected the respect in which a person (particularly a man) was held and the confidence people placed in his ability to deliver on his commitments. A person could

Society 25

be born into credit by virtue of their family’s status or wealth, but credit was less rigid than status and could be more easily gained or lost by the choices a person made. Being able to make good on promises, repay

debts, or avenge insults increased a man’s credit; failing to do any of these diminished it. In a mobile society where people met strangers on a regular basis, it was possible to garner credit, at least in the short term, through outward appearances: dressing the part, displaying skills or knowledge that suggested a creditable person, carrying oneself with a certain poise and self-confidence. London in particular was a place where Elizabethans were daily negotiating credit among themselves, jockeying for position in an environment where there were opportunities that might make a man’s fortune.

THE CHURCH

The Elizabethans inherited from the Middle Ages a social system in which church and state were regarded as inseparable. During the Middle Ages, every country in western Europe had adopted Catholicism as its state religion, and secular authorities worked closely with the church hierarchy to ensure religious conformity. It was widely assumed that without a shared structure of religious belief and practice, no society could survive. As Elizabeth’s chief minister, Lord Burghley, put it, “That state could never be in safety, where there was toleration of two religions.”6

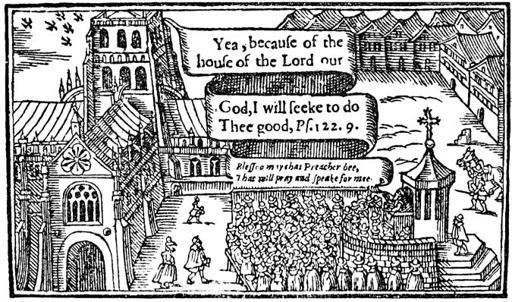

Religious change in the age of Reformation had only deepened the connection between religious and secular authority. When Henry VIII withA sermon outside St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. [

Shakespeare’s England

]

26

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

drew England from the Catholic Church, he replaced the pope with the king, making himself head of both church and state. Religious nonconformity was now tantamount to treason.

Henry had no desire to pursue Protestant reform, but there was a growing trend toward Protestant thought in England. The doctrinal differences between Catholicism and Protestantism were complex, but many of them hinged on the contrast between concrete and intellectual approaches to religion. Catholicism affirmed the importance of concrete observances, such as religious ritual, veneration of saints, and charitable deeds; the Catholic Church taught that such things had the power to bring people closer to God. Protestants generally rejected this idea and stressed a more abstract form of religion: a person would not go to heaven by doing good deeds but by having faith in God, and the word of the Bible was to be taken as more important than traditional religious practices. Protestant reformism gained the ascendancy under Edward VI, and during Mary’s reign, many English reformers deepened their Protestantism while in exile in Calvin’s Geneva.

For a Renaissance monarch, Elizabeth was unusually tolerant in matters of belief—she famously remarked that she had no desire to “make windows into men’s souls.” Yet like her predecessors she insisted on outward religious conformity, and she was fully prepared to inflict savage physical punishment on those who threatened to undermine her church.

The church that took shape during her reign was Protestant in its doctrine but still retained many of the outward trappings of Catholicism. The number of saints’ days was reduced, but they were not entirely eliminated; the garments worn by Elizabethan ministers were simpler than those of Catholic priests, but still more elaborate than the severe gowns worn in Geneva. Religious statuary was removed from the churches and wall paintings were covered over, but stained glass windows were allowed to remain, until normal wear and tear afforded an opportunity to replace them with clear panes. Monks and nuns had been abolished, but bishops and archdeacons continued to fulfill their medieval roles.

Administration of the Elizabethan church remained largely unchanged from the hierarchical structure inherited from Catholicism. At the base of the hierarchy was the parish church, typically serving a village or an urban neighborhood. Everyone was required to attend service at their parish church, and parishioners owed annual tithes amounting to a tenth of their income in money or goods. There were upwards of 9,000 parishes in the country, ranging in size from over 3,000 communicants to fewer than 10; a few dozen households or a couple of hundred people was a fairly typical parish population.

The right to nominate the parish priest and allocate the parish tithes was called an advowson. Many advowsons during the Middle Ages had

belonged to monasteries: with the dissolution of the monasteries, these were sold off with other monastic property, so that many Elizabethan

Society 27

advowsons had ended up in secular hands. Others belonged to schools or university colleges, serving as endowments to support the operations of the institution.

The right to collect the principal tithes from the parish church was called the rectory, and whoever held that right was called the rector. In a bit more than half the parishes in the country, the rector was actually the appointed minister. In the rest, the owner of the advowson held onto the rectory and appointed a vicar to minister to the parish. The rector paid the vicar a sal-ary, which in a rural parish might be supplemented by

small tithes

—the less valuable tithed produce of his parishioners—along with income from agricultural land that went with the vicar’s position, called the

glebe.

Inadequate funding could make it difficult for the church to attract skilled parish clergy. In 1576, an investigation in the bishopric of Lincoln found that one parish in six had no clergyman, and that in the archdeaconries of Lincoln and Stow only a third of the clergy had adequate knowledge of scripture for their duties. Such figures were worrisome to a government that feared efforts by Catholic priests and Protestant separatists to win converts from the English church, and concerted efforts by Elizabeth’s bishops generally succeeded in raising the quality of the parish clergy over the course of her reign.

The minister was assisted in his work by a clerk who kept the parish records and by a pair of churchwardens who managed the practical affairs of the church building, property, and finances. The churchwardens were also required to report to the church hierarchy on the state of their parish and to present cases of misconduct for prosecution by the church courts.

One or both churchwardens might be appointed by the vestry, a self-coopting board of leading parishioners. Upkeep of the parish church was offset by various sources of income such as the rental of pews, and some urban parishes owned substantial property on the side: in such cases the churchwardens had substantial administrative responsibilities that could include collecting rents from tenants, lending money, and buying and selling parish property.

The clergy were fewer in number than they had been during the Middle Ages, especially since there were no longer any monasteries. However, they still enjoyed a measure of prestige. A parish minister enjoyed the status of a low-ranking gentleman, while bishops sat in the House of Lords and had incomes not far below that of the peerage. The church was one of the best avenues by which a commoner might advance in society, and since the Catholic ban on clerical marriage had been lifted as part of the Protestant reformation, a clergyman could pass his status on to his family: Elizabeth’s bishops were mostly commoners by birth, but a third of their sons managed to establish themselves as landed gentry.

Activities of the parish priest were overseen by his superiors in the church hierarchy. Parishes were grouped into archdeaconries administered by an archdeacon and his staff. Archdeacons were subject to the authority

28

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

of a bishop—there were 24 bishoprics and 2 archbishoprics. Each bishop was overseen by one of the two archbishops, Canterbury and York, with the see of Canterbury enjoying some authority over York. At the apex of the hierarchy was the Queen, established by Parliament as supreme governor of the English church.

The medieval heritage of the Elizabethan church was manifested not only in the hierarchy, but in its jurisdiction over many aspects of life that today would be seen as secular matters. The church was charged with ensuring attendance at religious services, enforcing tithes, and punishing heresy, but it also had authority over matters such as marriage, wills, education, sexual behavior, and what could generally be termed personal morality. Marital disputes, disputed wills, paternity suits, and even charges of defamation were handled by the church’s consistory courts.

The court of first recourse sat under the authority of the archdeacon; decisions of the archdeacon’s court could be reviewed by the consistory court of the bishop or archbishop, with the archbishop of Canterbury’s Court of High Commission as the highest authority. Church courts could impose penances, including rituals of public humiliation, but they did not have the authority to inflict punishments of life or limb. Technically they were not even allowed to impose fines, although penances could be com-muted into monetary payments, and court costs could be assigned to the defeated party, making for de facto fines.

At every level, the staff of the court were not actually clergymen: laymen trained in civil law sat as judges, administered court business, and served as

proctors

(lawyers) on behalf of the plaintiffs and defendants.

Elizabeth’s policies stressed outward conformity of religion, or at least absence of obvious nonconformity. People were required to attend church each Sunday. The fine for nonattendance was initially set at 12 pence, and enforcement was lax in the early years of the reign. Those who failed to attend were known as

recusants

and consisted mostly of Catholics—most Protestants were able to attend in good conscience, even if they felt the church was less reformed than they might wish. People were also required to take communion three times a year. Public officials, teachers, and other persons of authority were required to take the Oath of Supremacy, swearing to uphold the English church and the Queen as its supreme governor. Beyond this, there was little persecution of people for their religious beliefs in the early part of Elizabeth’s reign, especially in comparison to the religious wars that were rocking the Continent at this time.

In fact, there were still quite a number of Catholics in England. They may have constituted some 5 percent of the population, and were especially numerous in the north. Elizabeth was inclined to let English Catholics believe as they pleased, but the level of tolerance extended to Catholics diminished from the late 1560s onward, as international tensions between Protestants and Catholics increased, and English Catholics were increasingly seen as a potentially dangerous fifth column. The situation was

Society 29

aggravated with the arrival of Mary Stuart in England as a possible Catholic claimant to the throne, and by Catholic participation in the Northern Rebellion of 1569. In 1570 the pope issued a decree officially deposing Elizabeth from the crown, making it very difficult to maintain loyalty both to the Catholic Church and to the Queen, and it was in this year that the Queen first began to execute Catholics for acts in support of the pope and his policies. Tensions rose even further in the 1580s when the pope sent Jesuit missionaries into England, with the intent of ministering to English Catholics and winning converts. The Jesuits were regarded as the worst of spies, and if caught, they were subject to torture and a protracted and agonizing execution.

Changing attitudes toward English Catholics can be traced in governmental policies: enforcement of recusancy laws began to intensify in the early 1570s; in 1581 the 12d. fine for recusancy was increased to a ruinous