Daily Life in Elizabethan England (4 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

Society

9

During the Middle Ages, society and the economy had been organized around people’s relationship to farmland. The relationship was understood as

holding

rather than owning: landholders at every level were called

tenants,

literally “holders.” (Technically this still holds true, as land ultimately belongs to the state that holds sovereignty over it, a fact occasionally exercised through the legal principle of eminent domain.) A medieval landholder inherited the right to occupy and use a certain landholding under terms established by custom. Theoretically, all land actually belonged to the sovereign monarch, and was passed downward in a hierarchical chain, each landholder providing payment to his over-lord in exchange for the landholding. Landholdings were inherited like other forms of property, but they were not owned outright: they could not be freely bought or sold, and it was very difficult in the Middle Ages to acquire land by any means other than inheritance. Since feudalism emerged at a time when there was limited cash in circulation, payment was in the form of service rather than money.

At the upper ranks of society, landholding was by

feudal

tenure, meaning that it was theoretically paid for with military service. When their lord called upon them, feudal tenants were expected to serve as mounted and armored knights with a following of soldiers. This was the aristocratic form of service, and landholders who held their land by feudal tenure were considered to be of gentlemanly birth, along with everyone in their families. Feudal landholdings carried with them a measure of legal authority over the landholding and its inhabitants, and gentle status in general went hand-in-hand with political influence, social privilege, and cultural prestige.

The smallest unit of aristocratic landholding was the manor, typically consisting of hundreds of acres of farmland. The manor often coincided physically with a village settlement and its farmlands, and it might also correspond to a parish in the hierarchy of the church. The medieval manor lord parceled out landholdings to his peasant tenants, keeping a portion in his own hands as

demesne.

The villagers held their land by

manorial

tenure, paying for it in annual rents of cash and goods, but above all through labor services that provided the manor lord with manpower to cultivate the demesne.

Everyone below the level of the manor lord was considered a commoner, although there were subdivisions of status among them. Some were freeholding peasants, whose rents and services were minimal and who were free to leave the manor if they chose. The majority were villeins or serfs, who owed several days of labor service a week and had limited personal rights and freedoms—they were not quite slaves, but they were in a position of servitude to their lord.

The functionality of this system rested on the culture’s respect for custom and inheritance. For aristocrat and commoner alike, the terms of a landholding were not negotiated personally, but were established by the

10

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

THE CLASS SOCIETY

In London, the rich disdain the poor; the courtier the citizen; the citizen the country man. One occupation disdaineth another: the merchant the retailer; the retailer the craftsman; the better sort of craftsmen the baser; the shoemaker the cobbler; the cobbler the carman [carter]. One nice dame disdains her next neighbour should have that furniture to her house or dainty dish or device which she wants. She will not go to church, because she disdains to mix herself with base company, and cannot have her close pew by herself. She disdains to wear that everyone wears, or hear that preacher which everyone hears.

Thomas Nashe,

Christ’s Tears over Jerusalem

(London: James Roberts, 1593), fols. 70v-71r.

traditional customs associated with that holding, passed down from parent to child across the generations.

The on-the-ground realities of medieval feudalism and manorialism

were complex, varying heavily with local circumstances, traditions, and history: it was never an organized system, but a characteristic pattern of organization that arose out of a shared set of circumstances. By the late Middle Ages, feudalism was being substantially transformed. By 1290, intermediate levels of feudal tenure had been eliminated, and all feudal land was held directly from the crown. At about the same period, military service was being replaced by cash payments: the king preferred to collect money to hire his own troops, rather than relying on the traditional service of feudal knights.

At the manorial level, customary service-rents proved similarly unsatisfactory to both lords and tenants in a rapidly changing economy, and labor services were being replaced by cash rents. As labor services declined, so too did serfdom, which was largely gone by the 1500s. When Henry VIII abolished the monasteries during the 1530s, a great deal of monastic land came onto the market; unlike traditional medieval holdings, this land could be freely bought and sold, further loosening the older strictures of feudal landholding. By Elizabeth’s day, feudal tenants and village freeholders were the effective owners of their land, while serfs had been transformed into renters.

THE ELIZABETHAN ARISTOCRACY

Although England was no longer a feudal society by the time Elizabeth came to the throne, feudal and manorial structures still played a major part in the social fabric. At the upper levels, feudalism provided the vocabulary of personal status that shaped the aristocratic hierarchy. This elabo-Society 11

rate hierarchy embraced only a tiny minority of the population: noblemen, knights, and squires together accounted for well under 1 percent of the population, and ordinary gentlemen for about 1 percent.

At the top of this hierarchy was the monarch, the titular sovereign owner of all land in the kingdom, and still one of the biggest actual landowners in the country. Below her was the peerage, heirs to the great nobles of the Middle Ages who had been able to ride to war with large followings of knights at their command. Titles of nobility were inherited: the eldest son inherited the title when his father died, while his siblings ranked slightly below. In descending order of rank, the titles were duke, marquis, earl, viscount, and baron or lord; their wives were called duchess, marchio-ness, countess, viscountess, and baroness or lady. The actual title was not the only criterion of aristocratic status. Many titles were relatively recent creations—nearly half the peerage were first or second generation when Elizabeth came to the throne—so the longer a title had been in the family, the more respect it enjoyed.

The total number of peers was never much above 60. This was a highly exclusive sector of society, but in contrast to the medieval peerage, heavily dependent on the favor of the monarch. Attempts to raise medieval-style aristocratic rebellions failed miserably in 1569 and 1601. Medieval peers had expected to occupy the highest positions in government, but Elizabeth preferred to rely on lower-ranking gentlemen to help shape and implement her policies. Nonetheless, families at this level of society enjoyed tre-mendous landed wealth—their annual incomes were typically thousands of pounds a year—as well as prestige and influence at a national level, and the peers were entitled to sit in the House of Lords when Parliament was in session.

A substantial gap separated the peers from the knights, the next level down in the feudal hierarchy. The title of knight was never inherited: it had to be received from the monarch or a designated military leader.

Knighthood in the Middle Ages had been a military title, but by the Elizabethan period, it had become a general mark of honor. As a knight, Sir William Cecil was addressed as Sir William, and his wife as Lady Mildred or Lady Cecil. There were probably about 300 to 500 knights at any given time: they were invariably wealthy landowners with substantial regional influence.

At the bottom of the feudal hierarchy were esquires (also called

squires) and simple gentlemen. The distinction between the two was not always clear-cut. In theory, an esquire was a gentleman who had knights in his ancestry, but he might also be a gentleman of especially prominent standing.

Knights, squires, and gentlemen and their families were sometimes

referred to collectively as the

gentry

—the total number of people in this category at the end of Elizabeth’s reign may have been around 16,000. The gentry enjoyed considerable power and prestige in their local regions, and

12

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

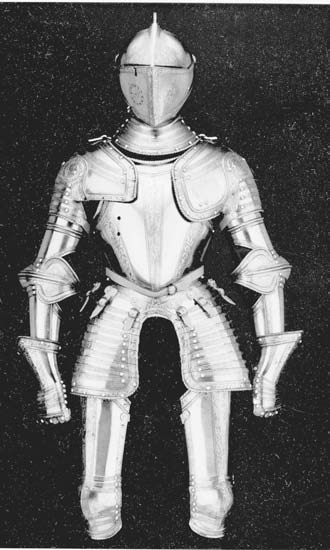

A cavalry armor of Henry Herbert, Earl

of Pembroke, c. 1565. [Higgins Armory

Museum]

the central government relied very heavily on them as a class to implement national policies at the local level, particularly through those who were chosen to serve as justices of the peace.

Although the gentry ranked far below the peerage in the Elizabethan hierarchy, contemporary culture saw the two as sharing the fundamental characteristic of gentle status that set them apart from commoners. The concept of the gentleman had been inherited from the Middle Ages, when gentle birth had meant belonging to the military class—those who fought on horseback in full armor. Such people had required sufficient income to allow them to purchase their expensive equipment and sufficient leisure to be able to practice the complex physical skills of mounted and armored combat. By the late 1500s, the military importance of the armored horseman was marginal, but the medieval tradition still shaped the concept of what made a gentleman. A classic Elizabethan definition of the gentleman is offered by Sir Thomas Smith in his treatise on English society,

De Republica Anglorum:

Who can live idly and without manual labor and will bear the port, charge, and countenance of a gentleman, he shall be called “master,” for that is the title which men give to esquires and other gentlemen, and shall be taken for a gentleman.2

Society 13

As Smith suggests, the principal characteristic of the gentleman was a leisured and comfortable lifestyle supported without labor. Traditionally, this meant having enough land to live off the rents. Gentry landholdings were large—50 to 1,000 acres represented the lower end of the scale, supporting an income of hundreds of pounds a year.

The manor remained the basic unit of landholding among the privileged classes. Manor lords still retained some legal jurisdiction over their manors—courts held in their name still ratified land transfers in the manor, promulgated bylaws, and resolved minor disputes in the community. But the manor lord rarely exercised legal powers in person, and for most, the manor was above all a source of income. Manorial land was now part of any ambitious investor’s portfolio. It offered a relatively stable annual income, as well as the social status that came with being a landowner. It could potentially be resold at profit when the market was favorable: old feudal manors were effectively sold through legal fictions and stratagems that circumvented feudal restrictions on property transfer, and former monastic landholdings were bought and sold freely.

A rich man and a beggar. [Traill and Mann]

14

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Absentee manor lords had become common, leaving manorial administration in the hands of hired stewards. Some manors were actually owned by consortiums of investors. Other manor lords took a more proactive approach to estate management, looking for ways to maximize the yield on their land through new farming techniques or by restructuring their tenants’ landholdings.

Although gentle status was associated with land ownership, not all gentlemen were landowners. In Smith’s formulation, gentlemen were expected to live comfortably without manual labor, but this did not necessarily require landed income. Government service was considered an acceptable occupation for a gentleman. Many gentlemen supplemented their income through commercial activity, while successful merchants moved into the gentry class by acquiring rural land. Military service, although no longer required, was still a gentlemanly occupation: the officers of Elizabeth’s army and navy were drawn from the gentry. In addition, anyone with a university education or working in a profession was considered a gentleman: such people included clergymen, physicians, lawyers, teachers, administrators, and secretaries (who were invariably men).