Daily Life in Elizabethan England (12 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

50

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

and remove their hat; depending on the relative ranks of the two, the hat would stay off unless the higher-ranking person invited the other to put it back (the modern military salute derives from this practice of doffing the hat). Children were expected to show great respect to their parents. Even a grown man would kneel to receive his father’s blessing and would stand mute and bareheaded before his parents. Status was also manifested in walking down the street: people of lower status were expected to

give the

wall

—allowing others to walk closer to the buildings while they walked on the street side, closer to the gutters that ran down the middle of a street.

Naturally, learning to be polite also meant learning what was rude, and Elizabethan children could learn bad habits at this age as well as good ones. Making a fist with the thumb protruding through the fingers—a gesture sometimes called the fig of Spain—was the equivalent of giving someone the finger today. A similarly insulting gesture was biting the thumb, still seen in parts of Europe today.

Elizabethan English had a particularly rich vocabulary for expressing anger or contempt. The four-letter words of modern English were familiar, though used more as nouns and verbs than as exclamations. Strong language usually took the form of blasphemy, for example swearing by various attributes of God (sometimes abbreviated to ’Ods or ’S):

Ods bodkins

meant “God’s little body”; the modern Londoner’s

strewth

comes from

“God’s truth”;

gadzooks,

from “God’s hooks [i.e., fingernails].” Those who had emotions to express but did not wish to cross the bounds of politeness or piety had plenty of milder options:

forsooth, i’ faith

(in faith),

la.

Elizabethan insults tell us much about the cultural values of the day.

Common types of insulting terms related to bodily uncleanness or

unhealthfulness (

dirty, poxy, lousy

), social inferiority (

peasant, churl, slave

), lack of intelligence (

fool, ninnyhammer, sot

), or subhuman status (

beast, cur,

dog

).

Most of these insults would not have literal implications, but others could be taken more seriously. In 1586 a Salisbury woman was accused of having ranted at a wife of a former mayor of the town, calling her “Mistress Stinks, Mistress Fart . . . Mistress Jakes, Mistress Tosspot, and Mistress Drunkensoul.”6 The first three insults were merely offensive, but the last two amounted to accusations of drunkenness, and could lead to a law-suit for defamation. Sexual insults could have even graver ramifications.

Terms that implied that a woman was sexually incontinent (

whore, jade,

quean

) had the potential to ruin her good reputation. For a man, one of the most serious insults was to imply unchastity on the part of his mother (

whoreson

) or wife (

cuckold

). Equally threatening were insults that accused a person of untruthfulness: to accuse a man of lying (called

giving him the

lie

) was to invite potentially lethal conflict. Elizabethans had to learn from a young age that words had consequences: a serious insult could lead to legal action, or even to a duel.

Elizabethan children like their modern counterparts found it hard to resist the forbidden fruits of rude speech and conduct: a major responsibil-Households and the Course of Life

51

ity of parents and teachers was to prevent rude conduct from becoming habitual, by beatings if necessary. Roger Ascham, who had been tutor to Queen Elizabeth when she was still a princess, was appalled by the laxity of some younger parents:

This last summer I was in a gentleman’s house, where a young child, somewhat past four years old, could in no wise frame his tongue to say a little short grace; and yet he could roundly rap out so many ugly oaths, and those of the newest fashion, as some good man of fourscore years old hath never heard named before; and that which was most detestable of all, his father and mother would laugh at it. I much doubt, what comfort, another day, this child shall bring unto them. This child using much the company of serving men, and giving good ear to their talk, did easily learn, what he shall hardly forget all the days of his life hereafter.7

As Ascham suggests, children were expected to learn the rudiments of religion from a very young age. By law, the parish minister was required to provide religious instruction on alternate Sundays and on all holy days.

All children over age 6 were required to attend, but most would already have received basic religious instruction at home. In particular, every child was expected to memorize the Ten Commandments, the Articles of Belief (also called the Creed—the basic statement of Christian belief), and the Lord’s Prayer. The major component of the minister’s instruction would be the catechism, a series of questions and answers regarding Christian belief. Parents who failed to send their children to receive this instruction might be prosecuted in the church courts, and children who could not recite the catechism might be required to do penance.

Play

Perhaps the most important part of the early learning process was play.

Babies in wealthy families were given smoothly polished pieces of coral set in silver handles with bells attached: the sound of the bells pleased the baby, who could also suck or chew on the coral much as modern babies have pacifiers and teething rings. Cheaper versions were made with boar’s teeth instead of coral. Whistles, rattles, and cloth or wooden dolls (called puppets or poppets) representing people or animals were also among the toys given to very small children. When toddlers were learning to walk, they might have a rolling walker that helped them along in the process.

As children grew, the range of toys and games grew with them. The ste-reotypical game for very young children was

put-pin,

which involved push-ing pins across a table, trying to get them to cross over each other. Toys for older children included tops, hobby-horses, whirligigs, and cheap cast pewter miniatures. The miniatures might be in the shape of people, household furnishings, and arms and armor—there were even tiny toy guns of brass designed to fire gunpowder. Broken tobacco pipes were used with a soap mixture for blowing bubbles. In the autumn when nuts began to harden,

52

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

children would play at Cob-Nut: nuts on strings were stuck against each other, the one whose nut broke first being the loser. Games played by older children included Tick (Tag), All-Hid (Hide and Seek), Hunting a Deer in My Lord’s Park (akin to Duck-Duck-Goose), LeapFrog, and Blind Man’s Buff. Other children’s pastimes included see-saws, swings, and mock military drill with toy drums, banners, and weapons.

Elementary Education

In spite of the vast social and economic differences that distinguished families from each other, the lives of very young children were remarkably uniform in many respects. At about age 6 this changed, as the social differ-entiations of class and gender began to play a real role. Girls remained in the world of women, wearing much the same clothing as they had when toddlers. Boys began to enter the world of men and abandoned their gowns in favor of the breeches worn by adult men. Both boys and girls began to be taught the skills appropriate to their rank in society.

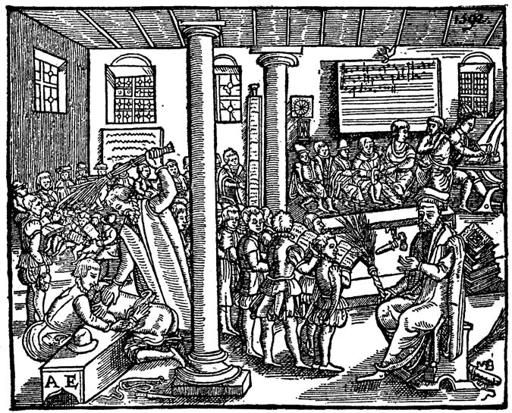

For boys of privileged families, this meant going to school. Only a minority of Elizabethan children received formal schooling, although the num-A 16th-century schoolroom. [Monroe]

Households and the Course of Life

53

ber was growing. There was no national system of education, but a range of independent and semi-independent educational institutions. Those children fortunate enough to have a formal education usually began at a

petty school.

Petty schools might be private enterprises or attached to a grammar school, but in many localities they were organized by the parish, and might be held by the parish minister in the porch of the church or in his own home. Petty schools were common—if there was none in a child’s own parish, there was almost certainly at least one in an adjoining parish. Some children learned informally through private teaching, either from a family member, or from a neighbor, who might be paid to provide instruction.

The petty school typically taught the fundamentals of reading and writing, and perhaps

ciphering

(basic arithmetic with Arabic numerals). There was no set curriculum: a child might start at any age at which he was ready to learn, and many only stayed long enough to acquire rudimentary literacy.

The content of petty school education was strongly religious. The first stage was to learn the alphabet from a

hornbook.

This was a wooden tablet with a printed text pasted on it, covered with a thin layer of translucent horn to protect the paper: the text typically had the alphabet across the top, with the Lord’s Prayer underneath. After learning the alphabet, the child would learn to read prayers and then move on to the catechism. Discipline was strict: schoolmasters had a free hand to use a birch rod to beat students for misbehavior or for academic failures. Most of the students were boys, but girls occasionally attended the petty schools. Masters at these schools were a mixed lot. Some were men of only small learning; some were women; some were in fact well-educated men—about a third of licensed petty school teachers may have been university graduates.

Literacy was expanding significantly during Elizabeth’s reign, although it was still the exception rather than the rule. Some 20 percent of men and 5 percent of women may have had some degree of literacy at the time of Elizabeth’s accession; by 1600 the figure may have risen to 30 percent for men and 10 percent for women. Literacy was generally higher among the privileged classes and townsfolk—perhaps 60 percent of London’s craftsmen and tradesmen could read in the 1580s; and of a sample of London women in 1580, 16 percent could sign their names. Literacy was also more common among the more radical Protestants, and in the south and east.

It tended to be lower among country folk and the poor, and in the north and west.8

What literacy means in an Elizabethan context could vary considerably.

Not everyone who could read was good at it, and being able to read did not necessarily mean being able to write; nor did the ability to sign one’s name mean that the person was a fluent writer. The diary of Lady Margaret Hoby, one of the few surviving texts from the hand of an Elizabethan woman, suggests that although she was a high-ranking gentlewoman

54

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

A LONDON SCHOOLBOY PREPARES FOR HIS DAY

Margaret the Maid

Ho, Francis, rise, and get you to school! You shall be beaten, for it is past seven. Make yourself ready quickly, say your prayers, then you shall have your breakfast.

Francis the Schoolboy

Margaret, give me my hosen; dispatch I pray you.

Where is my doublet? Bring my garters, and my shoes: give me that shoeing horn.

Margaret

Take first a clean shirt, for yours is foul. . .

Francis

Where have you laid my girdle and my inkhorn? . . . Where is my cap, my coat, my cloak, my cape, my gown, my gloves, my mittens . . . my handkerchief, my points, my satchel, my penknife and my books? Where is all my gear? I have nothing ready: I will tell my father: I will cause you to be beaten. Peter, bring me some water to wash my hands and my face.

. . . Take the ewer, and pour upon my hands: pour high.

Peter the Servant

Can you not wash in the basin? Shall you have always a servant at your tail?. . . .

Margaret

Have you saluted your father and your mother? . . .

Francis

Where is he?

Margaret

He is in the shop.

Francis

God give you good morrow, my father, and all your company.

Father, give me your blessing if it please you. . . .

Father

God bless thee . . . Now go, and have me recommended unto your master and mistress, and tell them that I pray them to come tomorrow to dinner with me: that will keep you from beating. Learn well, to the end that you may render unto me your lesson when you are come again from school.

Claudius Hollyband,

The French Schoolmaster

(London: Abrahame Veale, 1573), 62–66.

who read avidly and wrote daily, her spelling remained heavily phonetic compared to well educated men of her day.

Writing

The equipment used for writing was typically a goose-quill pen, an inkhorn, and paper. The quill was shaved of its feathers (contrary to our modern image), and a point or

nib

was cut into it. This was done with a small knife that folded into its own handle for safe transportation, to be brought out when the nib needed sharpening—the origin of the modern penknife.