Daily Life in Elizabethan England (20 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

The three-field system was predominant in the central part of England that produced the bulk of the country’s grain. As well as maintaining fertility, it diversified the village economy and covered core dietary needs:

Material Culture

93

in terms of modern nutritional science, carbohydrates came from grains, proteins from legumes and livestock, calcium from dairy products.

However open-field farming had its drawbacks. The system required a high level of communal collaboration, and it was not well suited to innovation, since any change required the cooperation of all the village landholders. This made it difficult for the open-field village to take advantage of agricultural innovations that were appearing in the late 1500s. Dutch farmers were developing new systems of crop rotation that would further enhance productivity, and some Englishmen were beginning to experi-ment with these techniques. Enhancing the soil with marl or lime was another way to increase production. Landowners who wanted to implement these emerging technologies often turned to enclosure as described in chapter 2.

The staple grain of the Elizabethan diet was wheat. Its high gluten content means that wheat bread rises well, and wheat has a higher caloric content by volume than other grains. However, it does not grow well in marginal soils or poor weather. Rye and oats were better suited to the less fertile regions of England, although they produce coarser and heavier bread, and are less nourishing. Barley was grown chiefly for brewing ale.

A major byproduct of grain production was straw, which was sometimes fed to the livestock (although they did not generally care for it), and had multiple other uses including making baskets, stuffing beds, thatching roofs, and strewing on the floor. Chaff, another grain byproduct, could be fed to livestock or used for stuffing beds.

The most important livestock in the three-field system were cattle.

Females were raised to become cows, providing offspring and milk. Males could be used in one of three ways. A few were allowed to grow up as breeding bulls. A larger number were gelded to become working oxen, useful for pulling plows and other heavy vehicles. The majority were destined to become beef: they were gelded while young and slaughtered once they were fully grown.

Other pasture animals included horses, sheep, and goats. Horses were the most common draft animals, since they could work faster and longer than oxen, though they were more expensive to feed and did less well plowing heavy soils; horses also served for riding. Sheep were raised for meat, milk, and wool; they were easier to graze than cattle in the highland zones in northern and western England. Goats were only a small part of the Elizabethan rural economy but did serve as a source of meat and milk for the very poor; they are hardy animals and could forage a living in some of the least fertile parts of the country.

Woolworking

Along with grains, sheep were the farmer’s main source of cash. Woolen cloth accounted for 80 percent of the country’s exports, while the produc-94

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

tion of woolen clothing for the domestic market was one of the principal engines of economic activity. There were nearly 11 million sheep in the country in 1558, almost four times the human population, and although sheep raising provided less employment per acre of land than agriculture, it did support a great deal of employment through the processes of converting the raw material into finished product.

Sheep were shorn once a year, during the summer. The fleeces were

typically sold to entrepreneurial clothiers, who sent their agents, or

factors,

through the countryside to purchase the raw material and arrange for the various stages of processing. Much of the work was done as a cottage industry, with the factors bringing the material to rural households, who processed it and returned it to the factor ready for the next stage.

The first step was to wash the fleece, after which it had to be carded to make it ready for spinning. This involved stroking the wool between a pair of special brushes so that all the strands were running parallel, free of knots and tangles; this was a simple job that was often assigned to children.

The carded wool was then ready to be spun into thread. Spinning

involved drawing out fibers from the carded mass and spinning them so that they would be tightly twisted. Wool fibers are covered with micro-scopic scales; when twisted, the scaly strands cling to each other, making it possible for them to form thread. Woolen thread could be spun with a drop spindle, essentially a weighted disk with a stick passing through the center. The spindle was suspended from the wool fibers and set spinning: the weight drew out the fibers, and the rotation twisted them into thread.

Alternatively, wool might be spun with a hand-cranked spinning wheel—

the treadle wheel was used only for spinning flax into linen thread. Spinning was proverbially the work of women, which is how unmarried

women came to be known as

spinsters.

After spinning, the thread was woven into cloth on a horizontal loom fitted with foot pedals that controlled the pattern of the weave. Weaving market-quality cloth required training and an expensive loom, and it was generally the preserve of professional male weavers, although like the female spinsters, they practiced their craft at home, receiving thread from the factor and returning the woven cloth.

Depending on the desired finish, the cloth might then be

fulled,

or washed, to shrink and felt it. This required beating the wet fabric and was often done in water-powered fulling mills. Fulling made the fibers join more tightly with each other, so that the fabric became stronger and denser, and therefore better at keeping out the English cold and rain.

Sometimes the wool would be left in its natural color, but usually it would be dyed. This might happen as the very last stage, but sometimes it was done before the wool was even spun—hence the expression “dyed in the wool.” Once finished, the cloth was ready to go to the tailor who made it into clothing.

Material Culture

95

Ironworking

Ironworking employed far fewer people than agriculture or even wool, but since it provided a material that was essential to the tools of almost every other trade, it was a crucial determining factor in the economy and technology of Elizabethan England. It was also among the most complex and industrialized processes used by the Elizabethans, giving a good idea of the extent and limitations of Elizabethan technology.

Iron naturally occurs in ores where the metallic iron is chemically combined with oxygen and physically mixed with other impurities, especially silicon-based compounds, to make up the stony ore. Iron ores are abundant in England, but once mined from the ground, the metal still needs to be isolated from the oxygen and silicates, a complex chemical and physical process known as smelting.

Traditional smelting in Elizabethan England was done in small batches on a

bloomery

hearth. Fragments of iron-rich ore were piled inside a small clay oven along with charcoal (partially combusted wood, which is almost pure carbon), and a

flux

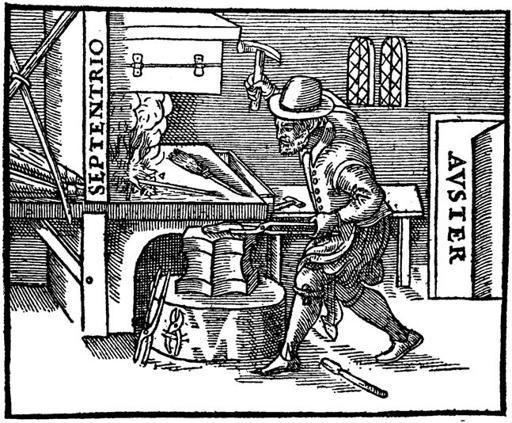

such as lime. The charcoal was ignited, and with the aid of a bellows was brought up to temperature. At about 800°C the oxygen in the ore would separate from the iron, combining with the car-A smith at work. [Gilbert]

96

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

bon in the furnace to escape as carbon dioxide gas. At about 1,200°C the silicates would combine with the flux and melt, flowing out of the ore as glassy

slag

to leave relatively pure iron. Some of the slag would remain trapped amidst the iron, so the furnace was broken open and the red-hot mass (called a

bloom

) was beaten, or

wrought,

with heavy hammers to drive out as much of the slag as possible. Sometimes this was done with water-powered triphammers. The product was wrought iron, pure enough to be ductile, although always with some lingering slag in the metal.

In Elizabethan England, this traditional means of iron production was being displaced by the blast furnace. The blast furnace was a large continuous-production installation served around the clock by teams of workers.

Water-powered bellows and a tall furnace stack allowed the blast furnace to reach higher temperatures than a bloomery hearth, while the addition of extra charcoal infused carbon into the iron to lower its melting point.

At the bottom of the furnace was a sand-covered work area. Molten

high-carbon iron was released from the furnace into rows of troughs dug into the sand where the iron could cool and harden. The resulting cast-iron ingots were known as

pigs

or

pig-iron

from the resemblance of the troughs to a row of piglets suckling from their mother. This cast iron could be used to make such items as cookware, but it was too hard to be worked with a hammer; a secondary heating process known as

fining

could be used to reduce the carbon content to a point where the iron was malleable.

Depending on the final carbon content, the resulting material might today be classed as steel (about 0.1% to 2% carbon) or wrought iron (under 0.1%

carbon). Steel could be heat-treated for extra hardness, making it the ideal material for blades and other kinds of cutting tools; iron is softer but less likely to break.

Crafts and Trades

Blast furnaces and fulling mills presaged the industrialization that would begin in earnest within a century and a half of Elizabeth’s death, but the bulk of the manufacturing in the 1500s was done by hand by individual craftsmen working from their homes. The independent craftsman combined the functions of employer, workman, merchant, and shopkeeper: he did his own work, and he marketed and sold his products from his own workshop. The craftsman’s shop was usually the front ground-floor room of his home; he would live upstairs with his family, servants, and apprentices, and might hire additional workers, called journeymen, who would assist him during the day but live elsewhere.

Not all wares were sold by the craftsman who produced them. Certain kinds of products were usually sold through a retailer who purchased from multiple suppliers to provide customers with a range of goods.

Grocers sold nonperishable consumables like dried fruits, sugar, spices, and soap; drapers offered a selection of cloth; mercers carried a variety of

Material Culture

97

household wares like lace, pins, thread, ribbons, and buttons; stationers retailed writing supplies.

Crafts were highly specialized based on the materials and technology used by the craftsmen, as well as the products they manufactured.

Woodworkers included carpenters, who worked with larger timbers and boards; turners, who shaped wooden utensils and furniture on lathes; and joiners, who built furniture with precisely fitted joints. Metalwork-ers included blacksmiths, who worked iron; braziers, who worked with copper alloys like brass; goldsmiths, who worked in precious metals; pewterers, who worked with pewter and related alloys; and plumbers, who worked with lead. Leather was worked at multiple stages by different specialists. The butcher slaughtered the animals and sold the skin to the tanner who treated it so that it would not decay—different types of tanners specialized in the skins of various types of animals. The processed leather then went to the currier who finished the surface. Finally it went on to the shoemakers, glovers, saddlers, and other craftsmen who made finished leather products.

Some of the materials used by Elizabethan craftsmen are no longer

familiar today. The vast numbers of cattle slaughtered for the table yielded byproducts that included bone and horn. Bone served as a cheap alternative to ivory. Horn is translucent, smooth, and watertight, and it can be molded when heated. It played a role similar to plastics today, being used for lantern panes, combs, inkhorns, drinking vessels, and spoons.

A large number of trades were involved in producing and retailing

food—a particularly important function in the towns, where many people had limited cooking facilities at home. Among the most common were butchers, bakers, cooks, brewers, vintners (wine merchants), and itinerant vendors who sold fresh foodstuffs from hand-held baskets.

Elizabethan England’s complex material culture required a well developed commercial network to distribute goods from the point of production to the various points of manufacture, and ultimately to the point of sale. At the top of the mercantile hierarchy were the merchants proper, who specialized in bulk trade over long distances, bringing English products to foreign markets, and importing materials and finished goods for which there was a demand at home. Fleets of water-going craft traversed the seas and plied England’s coasts and waterways, manned by seamen and watermen who spent most of their days in a world apart from that of most Englishmen. On land, a network of commercial carriers was emerging that transported goods by wagon, in particular bringing the products needed to support London’s massive and growing population. Some