Dog Eat Dog (11 page)

Authors: Chris Lynch

There was no Terry outside the O’Asis, and no Bobo. When I put my key in the deadbolt, I found it already open.

“How’d you get in here?” I said angrily as I pushed through the door. He sat with his feet up on a table.

“Jesus, don’t ask me stupid questions,” he sneered.

Then, as Duran ambled in behind me, the cockiness dropped from Terry’s face. “Holy

shit

,” he said, nearly tipping his chair over backward, catching himself on the table.

That felt good, and I held on to it for a bit, folding my arms and leaning on Duran. “So where’s Bobo?” I asked.

“He’s out back already,” Terry said, regaining his confidence quickly. “Bobo can’t wait. I don’t care how big your stupid spaniel dog is, Bobo’s gonna eat his ass out. ’Cause Bobo’s a

superior

animal.”

Already, it wasn’t fun anymore.

“Let’s get on with it,” I said.

“Fuckin’ let’s,” Terry said.

Duran and I followed Terry to the back door. With a dramatic flourish, he flung it open. There in the middle of the lot, Bobo lay with his chin in the dirt. He raised his head ponderously, looked at us, but showed nothing like emotion.

I felt the rumbling of Duran’s growl. I turned to see him rigid, the wiry, three-inch hairs standing straight up from the back slope of his skull almost all the way to his stumpy tail. All the teeth showed on one side of his mouth and he was locked into a pose like a giant pointer. He was leaning into me hard.

I looked back at Bobo, who slowly got to his feet. He looked at us, at Duran, and seemed to brace for something, but he didn’t snarl, didn’t get worked up. One ear looked about ready to fall off.

There it was. Everything. In one thirty-second mangling of that pathetic chump of a burned-out alcoholic dog, I was going to finally have it all. Terry was going to be gone. Gone for good. And I was going to get to watch him lick dirt all the way out. Finally, I was king. King of the game. King of

Terry’s

game.

Finally I saw it.

King of the losers.

“Close the door!” I shouted.

“What?”

“Shut the door,” I repeated. He did it. I started backing Duran away, across the bar, stroking and calming him. Terry followed us.

“What’s your problem?” Terry spat.

“It’s off. I’m out. He’s out,” I said.

“Bullshit,” he screamed.

“Ya, well I’m doing it. Come on, Duran, I’m taking you home.”

“You owe me a fight, boy,” Terry said.

“Screw.”

“Ya, well you still lose it all. You owe me the money,

and

”—he drew it out long, smiled, pointed at me—“annnnd, you’re comin’ home ta live. Wit me. I knew ya’d be back. You was never goin’ nowhere.”

I turned around, leaving Duran by the exit. I charged right up to Terry, stuck my finger in his face. “Screw,” I said. “I’m goin’ somewhere all right.”

He snatched the hand I had in his face. He bent it back at the wrist, bringing me to my knees. “No, screw

you

,” he said. Then he raised his other hand and slapped me. His slaps were harder than punches, with the whipping of his long bony fingers, and he slapped me again, and again, three times, four times. I could not get up off my knees as Terry slapped my face hard, pummeling the same side over and over.

“I should fuckin’ kill you,” he said. “Nobody’d fuckin’ care.” With those words he stopped slapping, held my arm straight up over my head, and kicked me high in the ribs with the toe of his work boot.

I fell, balling up under the table. The next thing I heard was the crashing of tables and chairs and scratching of claws. And Terry’s full-lung scream.

I looked up and Duran was on him, pinning him to the floor with two massive paws on Terry’s chest while biting, and yanking, on his arm.

“Duran,” I said, scrambling over to them.

“Shut up,” Terry screamed. The dog’s fangs were sunk completely into one of Terry’s biceps. He was clamped on it, squeezing. He looked like he was going to do it until he bit through. Which wouldn’t take much longer.

“Fuck off, Mick,” Terry screamed through his screams. “I told you before, you don’t never break up a dogfight.” As he spoke, Terry kept trying to tug his arm out of the dog’s grip, making it worse, making Duran dig further in. “I don’t need you. Fuck off.” Then he screamed, not at me or Duran, but into the air.

I listened to him, stood up, and stopped trying to stop Duran. The dog’s eyes rolled backward, showing all white, as he twisted his head and the arm, making Terry scream and lamely punch at Duran’s snout. Terry couldn’t do anything with the dog, so he turned on me again.

“Fuck off, I told ya. I don’t want you helpin’ me. Don’t do it. I wouldn’t do it for you. I wouldn’t ever do it for you, ya fuckin’ loser.”

That was it. It came through like a rocket burning away my fog.

It.

Finally. What I’d been looking for. I found it, and goddamn Terry was the one who gave it to me.

“You’re right,” I said. “You wouldn’t ever do it for me. And

that’s

the difference.”

Against Terry’s fading protests, I scrambled over to get Duran off him. “No,” I said. “Duran, no. Stop. Stop now. Stop.”

Duran growled, didn’t look at me. “Stop it!” I said, slapping his back. “It’s me.” I angled down so that my face was looking right into his. Finally he turned his eyes up to me.

The flesh of his lip curled up, showing all of his long yellow teeth. For me this time. I’d actually thought, until then, that I had control of all this.

He looked at me for several seconds, considering me. Then he opened his great, wonderful, killer jaws, and let Terry’s arm fall out. I jumped back. Duran looked coiled to leap on me until Terry rolled over, his mangled arm flopping after him like a string of raw sausages. When he caught Terry trying to wriggle spastically away, Duran slammed down on the back of my brother’s neck. He toggled his head all around as he seized it. Like a dog does with a bone. Just like a dog does with a bone.

Terry stopped telling me not to help him. Terry stopped telling me anything.

As hard as I could, I punched Duran on top of the head. I punched him again. He paid me no mind, even though I heard the crack, felt the swelling between my knuckles already. I ran to the refrigerator and threw all the contents across the floor toward the dog. I opened the back door to let Bobo in, but Bobo had no intention of coming in. How many times had Bobo heard Terry say it?

The loser is

supposed

to lose.

I

WAS ALMOST AT

Toy’s house before I even realized where I was walking. My left hand was throbbing, so I shifted the duffel bag to my right.

By the time Toy came down with his knapsack slung over his shoulder, I was sitting on the bike, my bag in my lap, pretending to ride. Like a kid. I had my bad hand curled and tucked up into my armpit, like I was lame.

“What happened to you?” he said, pointing at the hand.

I looked at it closely, as if there was an answer there, then looked back to Toy. “I fell down, in the forest.”

He nodded. “Ya,” he said, “I believe I heard it.”

“Is there still room on that train of yours?” I asked.

“Could be,” he said.

“Well, I don’t know if I’m going where you’re going, but I figure we can ride together for a while.”

Toy reached over to where his father’s motorcycle was parked right next to his own, pulled a helmet out of the sidecar, and stuck it in my hands.

“I suppose we could, for a while.”

Chris Lynch (b. 1962) was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the fifth of seven children. His father, Edward J. Lynch, was a Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority bus and trolley driver, and his mother, Dorothy, was a stay-at-home mom. Lynch’s father passed away in 1967, when Lynch was just five years old. Along with her children, Dorothy was left with an old, black Rambler American car and no driver’s license. She eventually got her license, and raised her children as a single mother.

Lynch grew up in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood, and recalls his childhood ambitions to become a hockey player (magically, without learning to ice skate properly), president of the United States, and/or a “rock and roll god.” He attended Catholic Memorial School in West Roxbury, before heading off to Boston University, neglecting to first earn his high school diploma. He later transferred to Suffolk University, where he majored in journalism, and eventually received an MA from the writing program at Emerson College. Before becoming a writer, Lynch worked as a furniture mover, truck driver, house painter, and proofreader. He began writing fiction around 1989, and his first book,

Shadow Boxer

, was published in 1993. “I could not have a more perfect job for me than writer,” he says. “Other than not managing to voluntarily read a work of fiction until I was at university, this gig and I were made for each other. One might say I was a reluctant reader, which surely informs my work still.”

In 1989, Lynch married, and later had two children, Sophia and Walker. The family moved to Roslindale, Massachusetts, where they lived for seven years. In 1996, Lynch moved his family to Ireland, his father’s birthplace, where Lynch has dual citizenship. After a few years in Ireland, he separated from his wife and met his current partner, Jules. In 1998, Jules and her son, Dylan, joined in the adventure when Lynch, Sophia, and Walker sailed to southwest Scotland, which remains the family’s base to this day. In 2010, Sophia had a son, Jackson, Lynch’s first grandchild.

When his children were very young, Lynch would work at home, catching odd bits of available time to write. Now that his children are grown, he leaves the house to work, often writing in local libraries and “acting more like I have a regular nine-to-five(ish) job.”

Lynch has written more than twenty-five books for young readers, including

Inexcusable

(2005), a National Book Award finalist;

Freewill

(2001), which won a Michael L. Printz Honor; and several novels cited as ALA Best Books for Young Adults, including

Gold Dust

(2000) and

Slot Machine

(1995).

Lynch’s books are known for capturing the reality of teen life and experiences, and often center on adolescent male protagonists. “In voice and outlook,” Lynch says, “Elvin Bishop [in the novels

Slot Machine

;

Extreme Elvin

; and

Me, Dead Dad, and Alcatraz

] is the closest I have come to representing myself in a character.” Many of Lynch’s stories deal with intense, coming-of-age subject matters. The Blue-Eyed Son trilogy was particularly hard for him to write, because it explores an urban world riddled with race, fear, hate, violence, and small-mindedness. He describes the series as “critical of humanity in a lot of ways that I’m still not terribly comfortable thinking about. But that’s what novelists are supposed to do: get uncomfortable and still be able to find hope. I think the books do that. I hope they do.”

Lynch’s He-Man Women Haters Club series takes a more lighthearted tone. These books were inspired by the club of the same name in the

Little Rascals

film and TV show. Just as in the Little Rascals’ club, says Lynch, “membership is really about classic male lunkheadedness, inadequacy in dealing with girls, and with many subjects almost always hiding behind the more macho word

hate

when we cannot admit that it’s

fear.

”

Today, Lynch splits his time between Scotland and the US, where he teaches in the MFA creative writing program at Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His life motto continues to be “shut up and write.”

Lynch, age twenty, wearing a soccer shirt from a team he played with while living in Jamaica Plain, Boston.

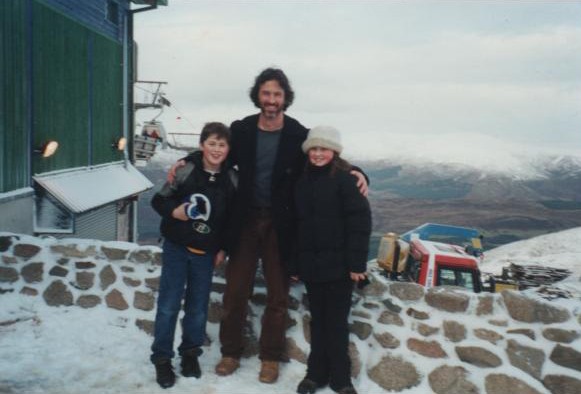

Lynch with his daughter, Sophia, and son, Walker, in Scotland’s Cairngorm Mountains in 2002.