Read Essence and Alchemy Online

Authors: Mandy Aftel

Essence and Alchemy (13 page)

Vanilla

The choicest variety, Bourbon vanilla, comes from Madagascar. Its aroma is extremely rich and sweet, with a rather woody, tobacco-like, balsamic body note. Is there anyone who is not intoxicated by the smell of vanilla and the vanilla-saturated memories it evokes?

Cognac

essence is produced by steam-distilling the lees left by the distillation of grape brandy. It has a delicate herbal aroma, with outstanding tenacity and great diffusive power. There are green and white varieties; I prefer the green, which is sweeter. Cognac works well with ambrette, bergamot, coriander, galbanum, lavender, clary

sage, and ylang ylang. It gives a blend life, brilliance, and a fresh, fruity, natural note.

essence is produced by steam-distilling the lees left by the distillation of grape brandy. It has a delicate herbal aroma, with outstanding tenacity and great diffusive power. There are green and white varieties; I prefer the green, which is sweeter. Cognac works well with ambrette, bergamot, coriander, galbanum, lavender, clary

sage, and ylang ylang. It gives a blend life, brilliance, and a fresh, fruity, natural note.

Â

Â

H

ere are suggestions for a set of base notes to get you started, along with two additional sets to consider purchasing as you can afford to and as you become eager to venture further afield.

(I have marked with an asterisk those that are more costly.)

ere are suggestions for a set of base notes to get you started, along with two additional sets to consider purchasing as you can afford to and as you become eager to venture further afield.

(I have marked with an asterisk those that are more costly.)

| Basic set of base notes: | |

| Benzoin | Buy the liquid resin, not “tears.” |

| Labdanum | |

| Oakmoss absolute | |

| Patchouli | |

| Tarragon | |

| Vetiver | |

| Second set of base notes: | |

| Frankincense | |

| Peru balsam | |

| * Sandalwood | The best comes from Mysore. |

| * Vanilla absolute | My favorite is from Madagascar. |

| Very special third set of base notes: | |

| * Ambrette seed | |

| * Civet absolute | |

| Cognac, green | |

| Costus | |

| * Spruce absolute, white and black | |

| Tea absolute | |

| Tobacco, blond | |

| * Tonka bean |

Blending chords are the building blocks of the perfumery process. They are combinations of essences of similar tenacityâtop, middle, or baseâthat are themselves blended together to make a perfume. In this chapter we are going to create a base chord that we will build upon in the next two chapters, layer by layer, until we have a perfume, which I have christened Alchemy. Later, in chapter 6, you will learn more about the overall principles of perfume composition so that you can begin experimenting with your own blends.

A solid base chord usually contains at least two and no more than five ingredients; three is a good number to start with. In each chord, one ingredient should shine, with the others augmenting and supporting it. This base chord includes

amber,

which is in itself a base chord, but functions well used as a single note to add to other base chords. (Amber has nothing to do with the semiprecious fossilized resin of the same name. It originally referred to the scent of ambergris, which was also called ambra, but now an amber note is usually one that has been created from labdanum combined with styrax, vanilla, civet, or benzoin. A popular base note in the Oriental family of perfumes, ambers are powerful and popular fixatives in general.

amber,

which is in itself a base chord, but functions well used as a single note to add to other base chords. (Amber has nothing to do with the semiprecious fossilized resin of the same name. It originally referred to the scent of ambergris, which was also called ambra, but now an amber note is usually one that has been created from labdanum combined with styrax, vanilla, civet, or benzoin. A popular base note in the Oriental family of perfumes, ambers are powerful and popular fixatives in general.

Here is a recipe for a very beautiful and simple amber that can be worn alone or used as a base for a perfume:

AMBER

Â

30 drops labdanum

120 drops benzoin

6 drops vanilla

120 drops benzoin

6 drops vanilla

Before you can measure the labdanum, you will probably need to heat it up so that it will flow; set the bottle of resin in a small bowl of

very hot water (just boiled) until it liquefies. Then measure the drops into a small bottle and add the benzoin and vanilla. Secure the bottle cap tightly and shake to mix. Label this bottle “Amber.”

very hot water (just boiled) until it liquefies. Then measure the drops into a small bottle and add the benzoin and vanilla. Secure the bottle cap tightly and shake to mix. Label this bottle “Amber.”

Â

For our perfume called Alchemy, we are going to create a base chord that is sultry and rich:

15 ml perfume alcohol

8 drops vanilla

5 drops benzoin

6 drops amber

8 drops vanilla

5 drops benzoin

6 drops amber

Measure the alcohol into a beaker. Add the remaining ingredients, stirring and smelling after each addition. You will notice that the benzoin extends the vanilla note and adds a softness to it. With the addition of the amber, there is a slightly richer and deeper tone to the blend. Pour the finished chord into a bottle and label it “Base/Alchemy.”

Â

Here are some other suggestions for combinations to try when composing base chords. The dominant note appears first.

Powdery

(sweet, dry, musky): opoponax, blond tobacco, Peru balsam

(sweet, dry, musky): opoponax, blond tobacco, Peru balsam

Woody:

sandalwood, frankincense, costus

sandalwood, frankincense, costus

Mossy

(earthy, herbaceous, ferny): vetiver, labdanum, lavender absolute

(earthy, herbaceous, ferny): vetiver, labdanum, lavender absolute

Sweet:

cocoa, cognac, vanilla

cocoa, cognac, vanilla

Sultry

(sensual, voluptuous, rich): vanilla, Peru balsam, oakmoss

(sensual, voluptuous, rich): vanilla, Peru balsam, oakmoss

Aromatic Stangas Heart Notes

Fragrance, with your inexplicable way of making a flower's essence as palpable as an animal's by bombarding us with molecules more astonishing than electric ions, are you perhaps a function more of our minds than our bodies? The hypersensitive, exposed to your power, stagger, swoon as if from an illness. Though a lover cured of love may be able to confront his now harmless “ex” face-to-face without a qualm, let him breathe one whiff of the old familiar perfume and be blanches, eyes filling with tears. Because Asmodeus, god of lechery, enlists fragrance as his assistant, filling the night with lethal honeysuckle, unfailing acacia, wanton lime-blossom, to ravage hearts that remember and shatter ones that resist.

â

Colette, “Fragrance”

66

Colette, “Fragrance”

66

65

65T

HE ARABS loved roses even more than we do. They preserved them by gathering the buds and placing them in earthenware jars that they sealed with clay and buried in the earth. When roses were required, they dug up the jar, sprinkled the buds with water, and left them to air until the petals opened. One sultan was so smitten with roses that he forbade anyone else to grow them. He dressed in pink in their honor and had his rugs sprinkled continually with rosewater.

As we know, flowers stand for passion and romance. The very word

deflowered

connotes initiation into sexual experience. Not only in their heady aromasâdramatic, intense, sweet (sometimes sickly sweet), even narcoticâbut in their very form and coloration, flowers are sexy. I like an Indian poet's description of a rose as like a “book of a hundred leaves unfolding,” but most comparisons are decidedly

more erotic. A full-blown rose is like a voluptuous woman; orchids recall the vulva; flowers open and close like receptive female genitalia. So, not surprisingly, when people think of perfume, they think of flowers. And indeed, floral essences are among the most important perfume ingredientsâand by far the most expensive. Flower absolutes are priced at up to eight thousand dollars a kiloânot that you would ever need so much.

deflowered

connotes initiation into sexual experience. Not only in their heady aromasâdramatic, intense, sweet (sometimes sickly sweet), even narcoticâbut in their very form and coloration, flowers are sexy. I like an Indian poet's description of a rose as like a “book of a hundred leaves unfolding,” but most comparisons are decidedly

more erotic. A full-blown rose is like a voluptuous woman; orchids recall the vulva; flowers open and close like receptive female genitalia. So, not surprisingly, when people think of perfume, they think of flowers. And indeed, floral essences are among the most important perfume ingredientsâand by far the most expensive. Flower absolutes are priced at up to eight thousand dollars a kiloânot that you would ever need so much.

Still for flowers

Not all flowers, however, can be made into ingredients for perfumery. One stem of a Casablanca lily can perfume a room with an intoxicating aromaâin fact, it is my favorite floral scentâbut, alas, that smell cannot be captured in perfume; lilies, along with a number of other florals, resist any form of scent harvesting. In fact, it is a telltale sign that a perfume is made from synthetics if it contains any of the following flowers, because they cannot be rendered naturally: freesia, honeysuckle, violet, tulip, lily, gardenia, heliotrope, orchid, lilac, and lily of the valley.

Nor can these scents be faked successfully, because floral essences

are so nuanced and complex, varying dramatically even among varieties of the same species. A rose is a rose is a rose, but not to the perfumer. Russian rose is softer, Indian thinner, Egyptian richer, Turkish sweeter, Bulgarian rounder, Moroccan brighter. Jasmine

sambac

is sharp, while

grandiflorum

jasmine is more full-bodied. Deepgreen Tasmanian boronia has a rich herbal scent, whereas the bright orange kind has a sweet-tart citrusy odor. Spanish, Tunisian, and French orange flower absolute all vary in sweetness and depth.

are so nuanced and complex, varying dramatically even among varieties of the same species. A rose is a rose is a rose, but not to the perfumer. Russian rose is softer, Indian thinner, Egyptian richer, Turkish sweeter, Bulgarian rounder, Moroccan brighter. Jasmine

sambac

is sharp, while

grandiflorum

jasmine is more full-bodied. Deepgreen Tasmanian boronia has a rich herbal scent, whereas the bright orange kind has a sweet-tart citrusy odor. Spanish, Tunisian, and French orange flower absolute all vary in sweetness and depth.

The heavy florals have an intensely narcotic aura. They induce a sense of receptivity and surrender, almost of being ravished. After working with them for a while, I often feel as if I have been drugged. Many of these intoxicating floral essences have a fecal undertone; indeed, that is the source of the yin-yang appeal of some of the most coveted perfumes. The magic ingredient is indol (sometimes spelled indole), a major element in jasmine, tuberose, and orange flowers, among others; it is also found in human feces. As chemist and perfume writer Paul Jellinek observes, “It is precisely

67

the odor of indol, reminiscent of decay and feces, that lends orange blossom, jasmine, tuberose, lilac, and other blossoms that putrid-sweet, sultry-intoxicating nuance which has led to the sum of these flowers and of their extracts as delicate aphrodisiacs, today as in the past.”

67

the odor of indol, reminiscent of decay and feces, that lends orange blossom, jasmine, tuberose, lilac, and other blossoms that putrid-sweet, sultry-intoxicating nuance which has led to the sum of these flowers and of their extracts as delicate aphrodisiacs, today as in the past.”

Indol cannot be synthesized successfully. It can be approximated, but the loss of its natural nuances extinguishes the synergistic effect they achieve. As Jellinek notes, attempts to replicate chemically the surprisingly high levels of indol that occur in natural floral essences result in an unpleasantly dominant note of indol and demonstrate the limitations of the synthetics in general. It is not that naturally occurring indol smells different than the synthetic, or that its chemical structure is different; it is that “the odor strength

68

and effectiveness of natural flower absolutes is never equaled or even approximated by artificial compositions of the same complexes,” because “nature, in the composition of its odor complexes, likes to use,

in addition to the quantitatively predominant and largely identified components, small or minute amounts of materials which, by virtue of their characteristic odor notes of great intensity, play a decisive role in the character of the entire complex and its delicate ânaturalness.' These materials are hard to identify due to the exceedingly low levels at which they occur.”

68

and effectiveness of natural flower absolutes is never equaled or even approximated by artificial compositions of the same complexes,” because “nature, in the composition of its odor complexes, likes to use,

in addition to the quantitatively predominant and largely identified components, small or minute amounts of materials which, by virtue of their characteristic odor notes of great intensity, play a decisive role in the character of the entire complex and its delicate ânaturalness.' These materials are hard to identify due to the exceedingly low levels at which they occur.”

As an isolated element, indol loses its magic, much as acting in a particular manner in an effort to be sexy often isn't. But as an element of a natural essence entwined with other essences in an intricate fragrance, indol walks the fine line between arousal and disgust, orchestrating a genuine eroticism. As in nature itself, complexity and context are the field conditions for awakening passion. No ingredient is necessarily crucial: roses themselves do not contain indol, but their odor is unarguably sexual. Moreover, as Jellinek rhapsodizes, “The opulently rounded shapes

69

,

70

of the petals of a rose in full bloom are suggestive of the mature female body and their rich red color evokes thoughts of lips and kisses. The austere form of the bud before blooming, which only subtly hints at the rounded abundance and fragrance of full maturity, and its opening to amorous life, exhuming a ravishing scent, are external manifestations of the flower's life processes which man sees and senses and which stimulate his erotic fantasies.” It is no coincidence that the roseâespecially the red roseâhas been considered

the

flower of love by every culture that has known it.

69

,

70

of the petals of a rose in full bloom are suggestive of the mature female body and their rich red color evokes thoughts of lips and kisses. The austere form of the bud before blooming, which only subtly hints at the rounded abundance and fragrance of full maturity, and its opening to amorous life, exhuming a ravishing scent, are external manifestations of the flower's life processes which man sees and senses and which stimulate his erotic fantasies.” It is no coincidence that the roseâespecially the red roseâhas been considered

the

flower of love by every culture that has known it.

Collecting tuberose at Grasse

A

lmost all floral essences are middle notes, or heart notes, and almost all middle notes are florals, although there is a smattering of herbs and spices as wellâclary sage, verbena, cloves, and cinnamon bark. Heart notes give body to blends, imparting warmth and fullness. In their boldness, sexiness, sincerity, and dearness, they are the perfect metaphor forâno, embodiment ofâpassion. When you put them into a blend, you're literally putting the heart into it; they are the tie that binds.

lmost all floral essences are middle notes, or heart notes, and almost all middle notes are florals, although there is a smattering of herbs and spices as wellâclary sage, verbena, cloves, and cinnamon bark. Heart notes give body to blends, imparting warmth and fullness. In their boldness, sexiness, sincerity, and dearness, they are the perfect metaphor forâno, embodiment ofâpassion. When you put them into a blend, you're literally putting the heart into it; they are the tie that binds.

In J. K. Huysmans's classic novel of aesthetic excess,

à Rebours,

the protagonist describes the creation of a heart chord: “First he made himself a tea with a compound of cassia and iris; then, completely sure of himself, he resolved to go ahead, to strike a reverberating chord whose majestic thunder would drown down the whisper of that artful frangipani which was stealing stealthily into the room.”

à Rebours,

the protagonist describes the creation of a heart chord: “First he made himself a tea with a compound of cassia and iris; then, completely sure of himself, he resolved to go ahead, to strike a reverberating chord whose majestic thunder would drown down the whisper of that artful frangipani which was stealing stealthily into the room.”

Floral heart notes can be combined into voluptuous chords that are sultry, sophisticated, radiant, narcotic, exotic. They bridge the distance between the deep, heavy base notes and the light, sharp top notes, rounding off the rough edges and making the perfume cohere as a whole. This requires an almost alchemical transformation: idiosyncratic and intense as they are on their own, they are smoothly integrated into the evolving fragrance, enlarging it not by imposing their will but by allowing their singular personalities to be subsumed into a greater whole.

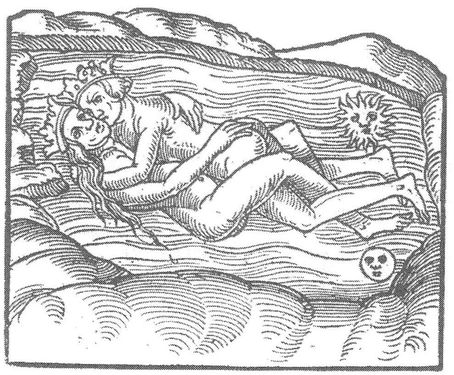

In this they mirror the alchemical phenomenon known as the

mystic marriage, in which opposite elements are combined and an entirely new substance emerges. The material, the

prima materia,

becomes spirit, and spirit in turn becomes concrete. This process of joining matter and spirit, or

coniunctio

, is a recurrent theme in alchemical writing, in which the dualities are conceived as masculine and feminine forces. As in perfumery, the transformation requires a medium, the soul. The resulting union, the mystic marriage of opposites, is often represented as a joining of sun and moon,

sol

and

luna,

frequently portrayed as king and queen.

mystic marriage, in which opposite elements are combined and an entirely new substance emerges. The material, the

prima materia,

becomes spirit, and spirit in turn becomes concrete. This process of joining matter and spirit, or

coniunctio

, is a recurrent theme in alchemical writing, in which the dualities are conceived as masculine and feminine forces. As in perfumery, the transformation requires a medium, the soul. The resulting union, the mystic marriage of opposites, is often represented as a joining of sun and moon,

sol

and

luna,

frequently portrayed as king and queen.

As always in these writings, alchemical symbols are susceptible

71

to multiple interpretationsâsun and moon can represent dual powers in the soul, soul and spirit, creativity and receptivity, and so on. But the representation of the mystic marriage in the ancient text is also overtly sexual, depicted in recurrent fanciful and mysterious images of sexual union. As Mark Haeffner observes in

A Dictionary of Alchemy,

“Graphic images of Coniunctio

72

in alchemy books are frank portrayals of sexual intercourse by a crowned couple. No mere chemical combination but an archetypal copulation of the reigning principles of nature at that time ⦠Sol is the masculine sun: fiery, active, fixed, symbol of sulfur. Luna is the volatile, feminine, liquid principle of the moon.”

71

to multiple interpretationsâsun and moon can represent dual powers in the soul, soul and spirit, creativity and receptivity, and so on. But the representation of the mystic marriage in the ancient text is also overtly sexual, depicted in recurrent fanciful and mysterious images of sexual union. As Mark Haeffner observes in

A Dictionary of Alchemy,

“Graphic images of Coniunctio

72

in alchemy books are frank portrayals of sexual intercourse by a crowned couple. No mere chemical combination but an archetypal copulation of the reigning principles of nature at that time ⦠Sol is the masculine sun: fiery, active, fixed, symbol of sulfur. Luna is the volatile, feminine, liquid principle of the moon.”

This is not a surprise. The alchemists saw sexuality as an integral aspect of transformation and ascribed a sexuality to all forces, incorporating it into much of their symbolic imagery. And coniunctio is a joining of opposites; it is inherently sexual and lusty. At the same time, “the concept of harmonizing

73

and unifying, integrating opposites, clearly has an esoteric, mystical significance.” Woman is represented as dissolving man, and man as making woman solid, just as spirit was believed to dissolve the body and the body to fix the spirit.

73

and unifying, integrating opposites, clearly has an esoteric, mystical significance.” Woman is represented as dissolving man, and man as making woman solid, just as spirit was believed to dissolve the body and the body to fix the spirit.

Other books

The Road to McCarthy by Pete McCarthy

Nobody Knows Your Secret by Green, Jeri

Corvus by Paul Kearney

Josette by Danielle Thorne

A deeper sleep by Dana Stabenow

The Baby Swap Miracle by Caroline Anderson

Hard Case Crime: Blackmailer by George Axelrod

Animating Maria by Beaton, M.C.

Flings by Justin Taylor

Appalachian Galapagos by Ochse, Weston, Whitman, David