Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (25 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

4.

Surgical correction of upper airways narrowing caused by polyps, enlarged tonsils or macroglossia can lead to significant improvement, but may not fully reverse the problem. Excision of soft tissue in the oropharynx is of value for well-selected patients.

5.

If there has been a recent stroke, observation may be all that is required, since respiratory function may improve with time. Patients with central sleep apnoea can often be successfully treated with bilevel positive airways pressure (BiPAP) ventilation.

Interstitial lung disease, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) may have a prolonged course, so patients are often available for the examinations. Discovering the aetiology may be difficult.

The history

The diagnosis may not be obvious until you examine the patient, at which stage you may have to ask further questions about the following:

1.

presenting respiratory symptoms (e.g. dry cough, dyspnoea, lethargy, malaise)

2.

whether the patient knows the cause of the respiratory symptoms

3.

the onset and duration of symptoms (these are clues) – pulmonary fibrosis has a very slow onset and patients are not acutely ill; if there is the insidious onset of cough, fever, malaise and myalgias over weeks to months, think about cryptogenic organising pneumonia (COP), which has a better prognosis and responds to steroids

4.

the patient’s gender and age (also clues) – for example, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) occurs essentially only in premenopausal women who often have a history of recurrent pneumothorax

5.

systemic symptoms – for example, weight loss, fatigue, fever, rash and arthralgia, which may indicate a systemic disease, particularly a connective tissue disease (scleroderma, systemic lupus, Sjögren’s syndrome or rheumatoid arthritis) or sarcoidosis (

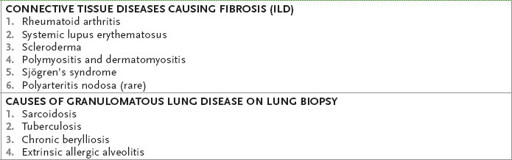

Table 6.10

)

Table 6.10

Fibrotic and granulomatous lung disease

6.

pre-existing asthma – which may suggest Churg Strauss syndrome (ask about renal disease)

7.

whether there is a history of haemoptysis and renal disease – which may indicate Goodpasture’s syndrome or SLE

8.

drug use – cardiac (e.g. amiodarone, hydralazine, procainamide), rheumatological (e.g. methotrexate, d-penicillamine), chemotherapeutic (e.g. busulphan, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide) and others (e.g. nitrofurantoin, bromocriptine)

9.

any history of radiotherapy

10.

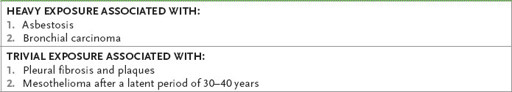

a detailed lifetime occupational history, such as exposure to mineral dust (silicosis, asbestosis, coal worker’s pneumoconiosis), chemical fumes (nitrogen dioxide, chlorine, ammonia) or organic dusts (

Table 6.11

)

Table 6.11

Asbestos and the lung

11.

occupational history consistent with hypersensitivity pneumonitis (e.g. bird fancier’s lung, farmer’s lung from mouldy hay or grain dust in grain elevators); ask about recurrent Monday chest tightness (e.g. byssinosis from cotton, flax or hemp dust)

12.

infections (e.g. aspiration pneumonia, miliary tuberculosis)

13.

investigations (e.g. high-resolution CT of the thorax, lung biopsy or bronchial lavage)

14.

treatment, if any

15.

social problems as a result of the chronic disability.

The examination

1.

Clubbing (consider idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, but also asbestosis); cyanosis and lower lobe crackles (fine, late, inspiratory) make the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) likely.

2.

If the signs suggest upper lobe pulmonary fibrosis, consider in your differential diagnosis silicosis, sarcoidosis, beryllium, cystic fibrosis, coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, eosinophilic granuloma, ankylosing spondylitis and tuberculosis. Lower lobe pulmonary fibrosis may be due to IPF, scleroderma, asbestosis, aspiration or drugs.

3.

Look for signs of associated systemic disease, as well as sarcoidosis and connective tissue disease that would rule out IPF. For example, erythema nodosum and anterior uveitis would suggest looking for evidence of sarcoidosis.

4.

Assess the severity of the disease (signs of pulmonary hypertension).

5.

Look for signs of drug side-effects (especially steroids).

Investigations

The goals of investigations are to find the aetiology, establish the severity of the disease and look for signs of active inflammation. If active inflammation is present, the condition may respond to immunotherapy (steroids or cyclophosphamide). If established fibrosis is present, such treatment is unlikely to help.

1.

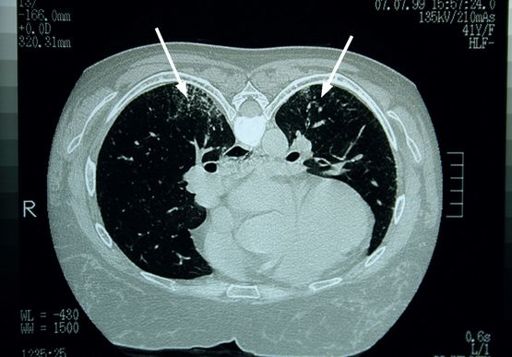

Chest radiography is the initial investigation, but may be normal (see

Fig 16.24

).

2.

High-resolution CT of the thorax is the investigation of choice (see

Fig 6.6

). It is the most sensitive non-invasive test. The changes of ILD are characteristic. Note whether there is a localised or diffuse abnormality or progressive massive fibrosis (caused by silicosis and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis).

FIGURE 6.6

CT scan of the thorax. There are increased lung markings posteriorly, more prominent on the right than on the left (arrows). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

3.

Pulmonary function tests usually reveal a restrictive pattern, with reduction of lung volumes and reduced transfer factor. An obstructive pattern may be seen in sarcoidosis, histiocytosis X (typically found in men who smoke and have a history of pneumothorax) and LAM.

4.

Blood gas levels will show hypoxia with a normal or low

Pa

CO

2

.

5.

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is often raised.

6.

There may be hypergammaglobulinaemia and a raised lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level. Eosinophilia may be a useful clue (

Table 6.12

). Serological testing for connective tissue diseases is routine.

Table 6.12

Causes of pulmonary infiltrate and eosinophilia (PIE)

P

rolonged pulmonary eosinophilia. This may be caused by: drugs (e.g. sulfonamides, sulfasalazine, salicylates, nitrofurantoin, penicillin, isoniazid, methotrexate, carbamazepine, imipramine, L-tryptophan); parasites (e.g.

Ascaris

); idiopathic

L

oeffler’s syndrome (benign and acute)

A

llergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (always associated with asthma)

T

ropical (e.g. microfilaria)

E

osinophilic pneumonia and vasculitis (e.g. polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis)

7.

A positive gallium-67 lung scan may indicate disease activity. Lung clearance studies using pertechnate may also be helpful (rapid clearance suggests active alveolitis).

8.

Bronchoalveolar lavage can be performed and is most helpful if there is haemophtysis or an acute disease onset. It is suggested that fibrosis on a transbronchial biopsy associated with a lavage showing a predominance of polymorphonuclear cells is less responsive to treatment. Lymphocytosis on lavage suggests drug-induced or granulomatous disease.

9.

Diagnoses likely to be made by transbronchial lung biopsy include sarcoidosis and lymphangitic spread of carcinoma; infection can be ruled out. Other specific diagnoses are not usually apparent.

10.

Open lung biopsy or video-assisted thoracoscopic biopsy may be required to confirm the presence of idiopathic ILD, but only if there is clinical uncertainty and the test result could change treatment.

Treatment

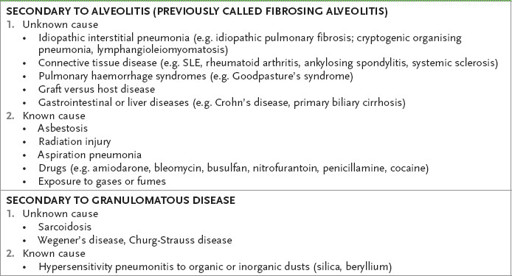

This depends on the cause (

Table 6.13

).

Table 6.13

Classification of interstitial lung disease (ILD)

SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

1.

Remove exposure, if appropriate.

2.

Treatment will not reverse established fibrosis.

3.

Steroids may help in COP, chemical injuries, hypersensitivity pneumonias (acute disease only), sarcoidosis (severe disease), histiocytosis X (controversial) and connective tissue disease. However, there is no evidence that steroids improve survival in these conditions and they are of no value in dust diseases.

4.

Treatment with prednisolone is usually begun at 1 mg/kg/day and reduced to half this dose after 4–12 weeks. Follow-up with measurement of spirometry, lung volumes and transfer factor is important to document response to treatment. Consider maintenance steroids in lower dose for patients who are improving or stabilised.

5.

Immunosuppressive agents, and especially azathioprine, may sometimes be of benefit and can be used in combination with low-dose steroids. Cyclophosphamide is now controversial. Antifibrotic agents are under trial – pirfenidone reduces lung decline. Colchicine in doses of 0.6 mg daily inhibits macrophage production of fibroblast growth factors, but its efficacy is controversial.

6.

N-acetylcysteine in combination with immunosuppression reduces deterioration of lung function. Treat any associated gastro-oesophageal reflux as it may aggrevate disease.

7.

General measures, such as administration of pneumococcal and influenza vaccines, may be indicated.

8.

Home oxygen therapy may provide symptomatic relief for hypoxaemic patients.

9.

Unilateral lung transplantation may be considered for some patients in the final stage of their disease.

Pulmonary hypertension

Many patients with this chronic and often severe illness will have raised pulmonary artery pressures as a result of a cardiac or respiratory illness. The patient may or may not be aware of this complication of the underlying disease, but it is essential for the candidate to know when to look for it. Idiopathic pulmonary hypertension (IPH) is a rare but important condition, which is diagnosed when other causes of pulmonary hypertension have been excluded. By definition, pulmonary hypertension is present when the mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) exceeds 25 mmHg at rest or 30 mmHg during exercise.