Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (23 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

For many of these patients the prognosis is poor. Sensitive questions about the patient’s expectations and plans for the future are important. Has there been adequate pain relief? How is the family coping? Does the patient plan to stay at home when things deteriorate? The examiners will expect a mature approach to the problem of an incurable disease and to the provision of palliative treatment.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

This general term is usually applied to patients with chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Although these two conditions are different, they usually occur together. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is common and presents major management problems. However, in the examination it is unusual for it to be the patient’s only medical problem. The vast majority of patients with COPD (more than 95%) are or

have been smokers. However, only about one-fifth of smokers experience a rapid enough decline in FEV1 ever to develop COPD.

The history

1.

Find out about symptoms, such as cough and sputum, dyspnoea, wheeze, impaired exercise tolerance, ankle oedema and weight loss. Remember that the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis is made largely from the history.

2.

Ask about precipitating causes of disease exacerbation, such as an upper respiratory tract infection, pneumonia, omission of drugs, symptoms of right ventricular failure, resumption of smoking, pneumothorax, sleep apnoea, oropharyngeal aspiration and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

3.

Enquire about smoking habits. Ask about the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the length of use (10 packet years of smoking is usually a prerequisite), as well as exposure to other people’s cigarette smoke – passive smoking. Absence of a smoking history weighs heavily against the diagnosis unless chronic asthma or alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency is present, or exposure to dust or fumes. Find out at what age the patient began to smoke. Commencement in adolescence when lung development is incomplete may lead to a more rapid decline in lung function.

4.

Ask about occupational history. This may be important, particularly as an additive feature if the patient has pneumoconiosis or has been exposed to toluene in plastics factories. Exposure to the fumes of solid fuel fires and to air pollution is also a risk factor.

5.

Ask about medications, especially steroids, home oxygen and bronchodilators.

6.

Enquire about management at home and work and the social effects of the disease. Find out in detail how limited the patient is physically and whether ADLs are managed. Ask about financial problems associated with chronic illness and symptoms of depression caused by chronic disability and loss of self-esteem.

7.

Ask about family history, such as alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency causing emphysema (autosomal codominant inheritance; the most common variant associated with severe deficiency of alpha1-antitrypsin (<11 mmol/L) is the

ZZ

allele, responsible for 2% of cases of emphysema in smokers). The condition should be suspected when COPD develops early or after minimal smoking exposure.

The examination

Examine the respiratory system carefully (see

Ch 16

). The examination may be normal until airway obstruction is moderately severe. Look particularly for:

1.

pursed-lip breathing (prolongs the expiratory time and may limit over-inflation) and use of accessory muscles

2.

cyanosis and polycythaemia (

note:

clubbing does not occur unless another disease such as carcinoma has supervened)

3.

intercostal recession

4.

prolonged forced expiratory time (reduced in both obstructive and restrictive lung disease)

5.

tracheal tug

6.

reduced diaphragmatic movements, over-inflation, reduced chest wall movement and expansion, Hoover’s sign (paradoxical inward movement of the lower costal margin during inspiration)

7.

reduced breath sounds with or without wheezes (rhonchi) and early coarse inspiratory crackles

8.

sputum

9.

signs of right heart failure

10.

signs of cachexia in patients with advanced disease (this is probably related to the increase in tumour necrosis factor alpha associated with chronic hypoxia rather than to the increased work of breathing)

11.

side-effects of treatment (e.g. tremor as a result of the use of beta-agonists, or the various changes caused by steroids).

Investigations

1.

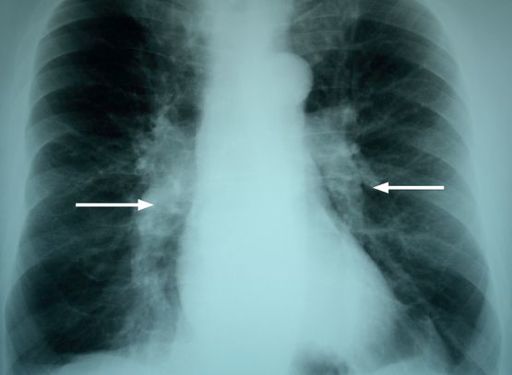

Chest X-ray film

(see

Fig 6.3

) – look for signs of hyperinflation (flat diaphragms and a vertical heart shadow) and cor pulmonale and exclude pneumonia. Radiolucent bullae may be visible; they are very specific for emphysema. The X-ray may be normal if the patient has mild disease. High resolution CT of the chest is more often performed and is more specific for emphysema.

FIGURE 6.3

COPD. Note the overinflated lungs, flat hemi-diaphragms and prominent pulmonary arteries (arrows), a sign of pulmonary hypertension. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

2.

Ventilatory function tests

– look for a considerable reduction of the FEV1/FVC (forced vital capacity) ratio (<0.70). A normal FEV1 excludes the condition. The amount of reversibility should be tested with bronchodilators. An increase in FEV1 or FVC of more than 15% and of at least 200 mL is considered significant. Complete, or almost complete, reversibility means that the diagnosis is asthma rather than COPD. Some asthmatics smoke and have both conditions; many smokers claim to have asthma but have only COPD. Vital capacity or total lung capacity may be falsely decreased if measured by gas dilution techniques because of the non-homogeneity of ventilation in COPD. The diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide is reduced in emphysema – a value of <50% is associated with exertion-induced hypoxia.

3.

Arterial blood gas levels

– look for respiratory failure at rest. The demonstration of significant hypoxia (usually a

Pa

O2 of <55 mmHg, or <59 mmHg if the patient has cor pulmonale) is required for the prescription of home oxygen treatment. Ventilatory failure is defined as

Pa

CO2 of >45 mmHg.

4.

Haemoglobin value

– look for polycythaemia.

5.

Sputum culture

– will usually grow

Haemophilus influenzae

,

Streptococcus pneumoniae

or

Moraxella catarrhalis

during exacerbations

and

remissions.

6.

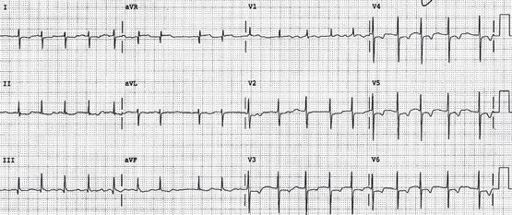

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

– look for signs of right ventricular hypertrophy and multifocal atrial tachycardia, which can complicate chronic lung disease (see

Figs 6.4

and

6.5

).

FIGURE 6.4

COPD. There is atrial fibrillation with a moderately rapid ventricular response rate. There are prominent R waves in V1 and there is marked RAD (right-axis deviation) (+110°). The right precordial T wave inversion suggests right ventricular ‘strain’.

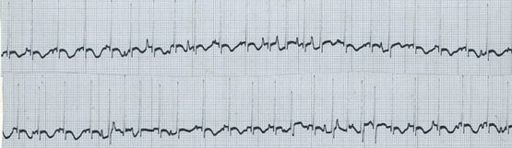

FIGURE 6.5

Multifocal atrial tachycardia L2 strip.

7.

Alpha

1

-antitrypsin measurement

– this is now generally recommended. It should particularly be considered if the patient has never smoked or has associated cirrhosis or basilar emphysema, or rarely subcutaneous nodules from panniculitis.

8.

Assessment of nutrition

– body mass index (BMI = weight in kg/height in cm

2

), grip strength, serum albumin, calcium and phosphate levels.

9.

Exercise testing

– to assess the need for ambulatory oxygen therapy and the degree of disability if there are discrepancies.

Differential diagnosis

1.

Asthma

Features suggesting asthma:

a.

non-smoker

b.

onset in childhood

c.

family history of allergy

d.

episodic attacks and also nocturnal symptoms

e.

a rapid response to treatment, especially steroids

f.

eosinophilia in the sputum

g.

atopic diathesis

h.

reversibility of obstruction.

2.

Bronchiectasis

Features suggesting bronchiectasis:

a.

daily sputum production with or without haemoptysis

b.

onset in childhood

c.

recurrent chest infection

d.

clubbing.

Treatment

1.

The patient should stop smoking, as this decreases sputum production and bronchospasm and may reduce the rate of decline in lung function to that of a non-smoker (smoking cessation has been shown to prolong life). The candidate should have an approach to the treatment of nicotine addiction. This may involve the temporary use of nicotine substitutes, psychological counselling and encouragement, or the use of drugs such as bupropion.

2.

Antibiotics can be used to shorten exacerbations (long-term chemoprophylaxis is indicated if there are four or more episodes a year), such as amoxycillin or doxycycline, given as a course at home at the first sign of purulent sputum. Remember that 25% of

H. influenzae

and 75% of

M. catarrhalis

infections are ampicillin-resistant.

3.

Regular bronchodilators are of value:

•

Beta

2

-agonists from metered-dose inhalers form the basis of treatment. A small change in FEV1 and FVC may produce considerable subjective improvement. Some patients find the inhaler devices difficult to use.

•

Inhaled long-acting anticholinergic drugs, such as tiotropium bromide, provide symptomatic improvement and reduce exacerbations, but do not prolong life.

•

Inhaled steroids in high doses (e.g. 400 μg beclomethasone) reduce the rate of episodes of exacerbation, but should be discontinued if after a trial of 4–8 weeks of treatment there is no clinical or spirometric improvement.

Candidates should have a strategy to ensure effective use of the best device for a particular patient. Long-acting drugs, such as salmeterol, provide longer acting bronchodilatation and are at least more convenient. Oral theophylline derivatives may have an additive effect with beta

2

-agonists, perhaps because they improve respiratory muscle function. They are prescribed much less often now, partly because they cause oesophageal reflux, cardiac arrhythmias, nausea and insomnia, and partly because they are not very effective. Antitussives and mucolytics are controversial, but may be useful to prevent exacerbations.

When patients do not improve, consider problems with adherence or technique.