Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (81 page)

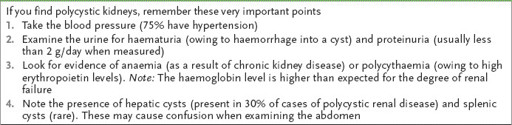

FIGURE 16.26

Right upper lobe fibrosis. Note the loss of volume and increased lung markings (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

FIGURE 16.28

CT chest showing pulmonary haemorrhage in a patient with Goodpasture’s syndrome. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

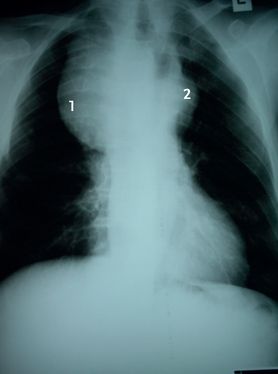

FIGURE 16.29

Retrosternal mass goitre (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

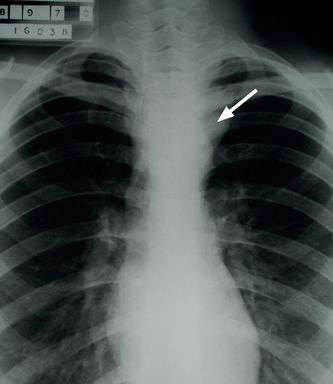

FIGURE 16.30

Retrosternal mass thoracic aortic aneurysm (1) and pulmonary metastases (2). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

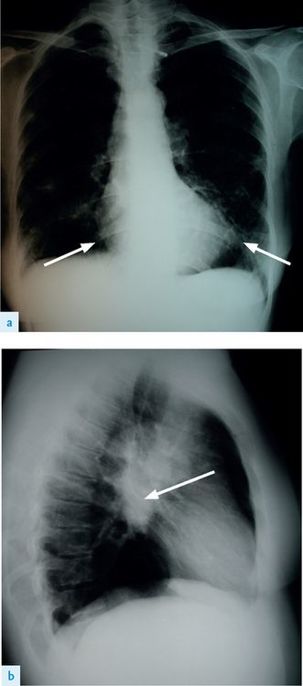

FIGURE 16.31

(a) Chest X-ray showing Wegener’s granulomatosis. Note infiltrates and destructive changes.

(b) Lateral view. Note infiltrates and destructive changes. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

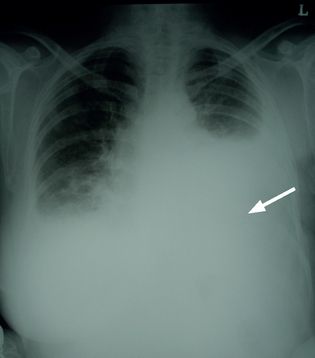

FIGURE 16.32

Large left pleural effusion (arrow). Note previous left mastectomy. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

FIGURE 16.33

(a) Sarcoidosis basal infiltrate (arrows). (b) Hilar lymphadenopathy (arrow). Figures reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

The gastrointestinal system

The abdominal examination

‘This 60-year-old man has had episodes of abdominal discomfort. Please examine his abdomen.’

Method (see

Table 16.16

)

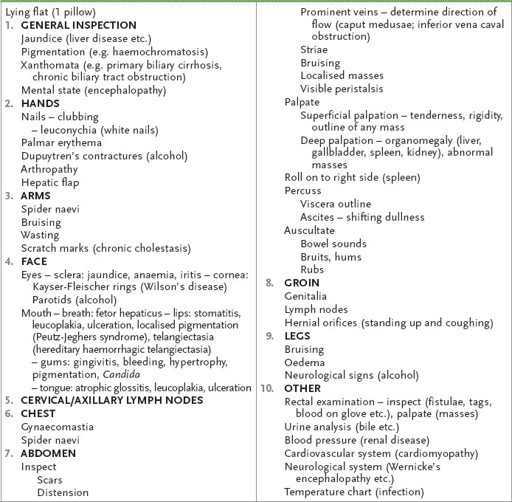

Table 16.16

Gastrointestinal system examination

1.

Position the patient correctly, with one pillow for the head and complete exposure of the abdomen.

2.

Briefly look at the patient’s general appearance and inspect particularly for signs of chronic liver disease and renal disease.

3.

Inspect the abdomen from the side, squatting to the patient’s level. Large masses may be visible. Ask the patient to take slow, deep breaths –an enlarged liver or spleen may be seen to move downwards during inspiration. Stand up and look for scars, distension, prominent veins, striae, bruising and pigmentation.

4.

Palpate lightly in each quadrant for masses (see

Tables 16.17

–

16.22

). Ask first whether any particular area is tender (to avoid causing pain and also to obtain a clue to the site of possible pathology). Next palpate more deeply in each quadrant and then feel specifically for hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. A palpable liver may be a result of enlargement or ptosis. If there is hepatomegaly (see

Table 16.17

), confirm with percussion and estimate the span (normal span is approximately 12.5 cm). The same procedure is followed for splenomegaly (use a two-handed technique) (see

Table 16.21

). Percussion is useful to exclude splenomegaly (over the lowest intercostal space in the left anterior axillary line: if dull in full inspiration, suspect splenomegaly and palpate again

1

). Always roll the patient on to the right side and palpate again if no spleen is palpable. Be seen to watch the patient’s face intermittently for signs that the examination is uncomfortable.

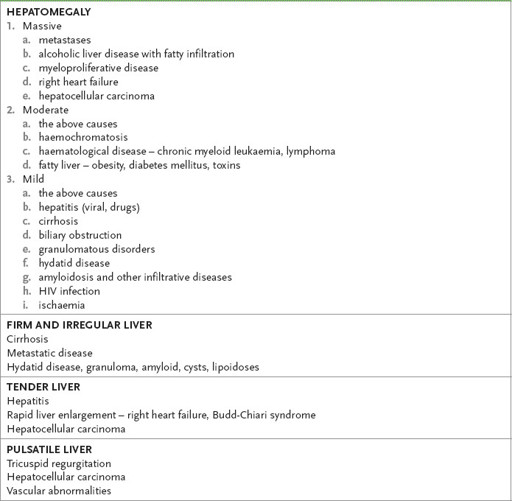

Table 16.17

Differential diagnosis in liver palpation

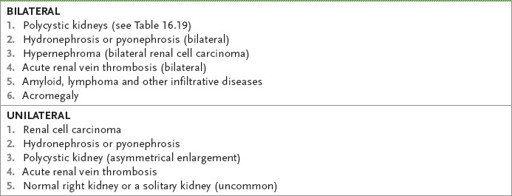

Table 16.18

Causes of renal masses

Note:

In very thin patients, bilateral renal enlargement owing to early diabetic nephropathy or nephrotic syndrome is occasionally detectable.

Table 16.19

Adult polycystic kidneys