Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (92 page)

FIGURE 16.82

X-ray of the pelvis of a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Note the lateral bridging syndesmophytes (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

The cauda equina syndrome

Back, buttock and leg pain

Saddle sensory loss

Lower limb weakness

Loss of sphincter control

The nervous system

Cranial nerves

There will usually be some direction from the stem, sometimes to the upper or lower cranial nerves. The introduction may vary, from a problem with vision, speech or swallowing to a history of neck surgery or trauma.

Method

1.

Inspect the head and neck briefly first. Have the patient sit over the edge of the bed facing you and look for any craniotomy scars (often well disguised by hair), neurofibromata, Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, Paget’s disease, facial asymmetry and obvious ptosis, proptosis, skew deviation of the eyes or pupil inequality.

2.

Look for the characteristic facies of myasthenia gravis or myotonic dystrophy.

FIRST NERVE

1.

Ask the examiners whether they want you to test smell. They will rarely allow you to proceed as it is time-consuming and not usually fruitful in examinations. If you are required to test smell, a series of sample bottles will be provided by the examiners containing vanilla, coffee and other non-pungent substances. Remember to test each nostril separately (see p. 415 for the causes of anosmia).

HINT

Testing upward gaze in the extreme lateral position will often reveal limitation in normal people.

SECOND NERVE

2.

Test visual acuity (with the patient’s spectacles on, as refractive errors are not cranial nerve abnormalities) using a visual acuity chart. Test each eye separately, covering the other eye with a small card.

3.

Examine the visual fields by confrontation using a red-tipped hatpin, making sure your head is level with the patient’s head. A red hatpin enables you to detect earlier peripheral field loss. Test each eye separately. If the patient has such poor acuity that a hatpin is difficult to use, map the fields with your fingers. When you are testing the patient’s right eye, he or she should look straight into your left eye. The patient’s head should be at arm’s length and he or she should cover the eye not being tested with a hand. Bring the hatpin from the four main directions diagonally towards the centre of the field of vision.

4.

Next map out the blind spot by asking about disappearance of the hatpin lateral to the centre of the field of vision of each eye. Only a gross enlargement may be detectable by comparison with your own blind spot.

5.

Look into the fundi (p. 414).

THIRD, FOURTH AND SIXTH NERVES

6.

Look at the pupils. Note the shape, relative sizes and any associated ptosis. Use your pocket torch and shine the light from the side to gauge the reaction to light on both sides. Do not bore the examiners by shining the light repeatedly into each eye – practise assessing the direct and consensual responses rapidly.

7.

Look for the Marcus Gunn phenomenon (afferent pupillary defect) by moving the torch in an arc from pupil to pupil. The affected pupil will paradoxically dilate after a short time when the torch is moved from a normal eye to one with optic atrophy or very decreased visual acuity from other causes.

8.

Test accommodation by asking the patient to look into the distance and then at your red hatpin placed about 15 cm from his or her nose.

9.

Assess eye movements with both eyes first. Ask the patient to look voluntarily and quickly from left to right and then to follow the red hatpin in each direction – right and left lateral gaze, plus up and down in the central position. Look for failure of movement and nystagmus.

HINT

Sometimes reduced eye movement will be detected only when the patient looks quickly from one side to the other.

10.

Ask about diplopia (double vision) when the eyes are in each position. For complex lesions assess each eye separately. Move the patient’s head if he or she is unable to follow movements. Beware of strabismus.

HINT

Subtle mystagmus is normal at the extremes of gaze.

HINT

Upward gaze is normally limited in elderly patients.

FIFTH NERVE

11.

Ask permission first to test the corneal reflexes. Make sure you touch the cornea (not the conjunctiva) gently with a piece of cotton wool. Come in from the side and do this only once on each side. If the nerve pathways are intact, the patient will blink both eyes. Ask whether he or she can actually feel the touch (V is the sensory component).

HINT

Corneal reflex: when there is an ipsilateral seventh nerve palsy, only the contralateral eye will blink – sensation is preserved (nerve VII is the motor component). Also, with an ipsilateral seventh nerve palsy, the eye on the side of the lesion may roll superiorly with the corneal stimulus (‘Bell’s phenomenon’).

12.

Test facial sensation in the three divisions: ophthalmic, maxillary and mandibular. Use a pin first to assess pain. Map out any area of sensory loss from dull to sharp and check for any loss on the posterior part of the head (C2) and neck (C3). Light touch must be tested also, as there may be some sensory dissociation.

HINT

A medullary or upper cervical lesion of the fifth nerve causes loss of pain and temperature sensation with preservation of light touch. A pontine lesion may cause loss of light touch with preservation of pain and temperature sensation.

13.

Examine the motor division by asking the patient to clench his or her teeth (feeling the masseter muscles) and open the mouth; the pterygoid muscles will not allow you to force it closed if the nerve is intact. A unilateral lesion causes the jaw to deviate towards the weak (affected) side.

HINT

Occasionally myasthenia affects the facial muscles. If you suspect myasthenia because of eye signs it might be worth testing for the

transverse smile

sign. Weakness of the levator muscles of the mouth makes an attempt at prolonged smiling look more like a grimace.

14.

Always test the jaw jerk (with the mouth just open, the finger over the jaw is tapped with a tendon hammer). An increased jaw jerk occurs in pseudobulbar palsy.

SEVENTH NERVE

15.

Look for facial asymmetry and then test the muscles of facial expression. Ask the patient to look up and wrinkle the forehead. Look for loss of wrinkling and feel the muscle strength by pushing down on each side. This is preserved in an upper motor neurone lesion because of bilateral cortical representation of these muscles.

16.

Next ask the patient to tightly shut the eyes – compare how deeply the eyelashes are buried on the two sides and then try to open each eye. Ask the patient to grin and compare the nasolabial grooves.

17.

If a lower motor neurone lesion is detected, quickly check for ear and palatal vesicles of herpes zoster of the geniculate ganglion – the Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Examining for taste on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is not usually required.

EIGHTH NERVE

18.

Whisper a number softly about 0.5 m away from each ear and ask the patient to repeat the number. Perform Rinne’s and Weber’s tests with a 256-hertz tuning fork. If indicated, ask for an auriscope (wax is the most common cause of conductive deafness).

NINTH AND TENTH NERVES

19.

Look at the palate and note any uvular displacement. Ask the patient to say ‘aaah’ and look for asymmetrical movement of the soft palate. With a unilateral tenth nerve lesion the uvula is drawn towards the unaffected (normal) side.

20.

Testing the gag reflex is traditional, but adds little to the examination. If the palate moves normally and the patient can feel the spatula, the same information is obtained (the ninth nerve is the sensory component and the tenth nerve the motor component): touch the back of the pharynx on each side. Remember to ask the patient whether he or she feels the spatula each time. You may not attain top marks if the patient vomits all over the examiners. If the spatula is used correctly, the patient will gag only if the reflex is hyperactive.

21.

Ask the patient to speak (to assess hoarseness) and to cough (listen for a bovine cough, which may occur with a recurrent laryngeal nerve lesion).

Note:

You will not usually be required to test taste on the posterior third of the tongue (i.e. ninth nerve).

ELEVENTH NERVE

22.

Ask the patient to shrug the shoulders and then feel the trapezius bulk and push the shoulders down. Then instruct the patient to turn his or her head against resistance (your hand) and also feel the muscle bulk of the sternomastoids (

Fig 16.83

sternocleidomastoid wasting).

FIGURE 16.83

Left-sided sternocleidomastoid wasting.

TWELFTH NERVE

23.

While examining the mouth, inspect the tongue for wasting and fasciculation (best seen with the tongue not protruded, and which may be unilateral or bilateral).

HINT

Take time to inspect the tongue. Fasciculations and wasting are easily missed but are very important in the diagnosis of a lower motor neurone twelfth nerve palsy.

24.

Ask the patient to protrude the tongue. Look again for fasciculation and wasting. With a unilateral lesion it deviates towards the weaker (affected) side.

25.

The way to finish your assessment depends entirely on your findings. For example, if you discover evidence of a particular syndrome (such as the lateral medullary syndrome), you should proceed to confirm your impressions by examining more peripherally, if allowed (especially for sensory long tract and cerebellar signs, see below).

HINT

If you have discovered multiple lower cranial nerve palsies, you would want to assess, among other features, the nasopharynx for signs of tumour and the neck for scars and radiotherapy changes.

26.

Auscultating for carotid or cranial bruits (over the mastoids, temples and orbits), as well as taking the blood pressure and testing the urine for sugar, are relevant.

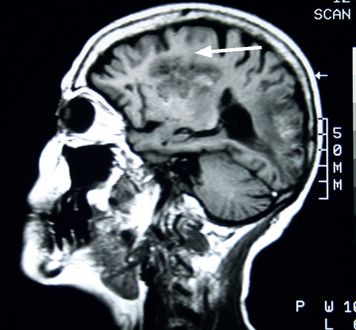

Relevant investigations are likely to be CT or MRI scans. These are not always easy for physicians to report. Candidates would hope to have a good idea where in the brain or the spinal cord the abnormality is likely to be present. Only scans with quite obvious abnormalities are likely to be used for the exam (see

Fig 16.84

) (because the examiners are otherwise more likely than not to have little idea).

FIGURE 16.84

MRI scan of a right-handed woman with right hemiplegia and aphasia. There is a large left middle cerebral artery stroke with haemorrhagic transformation (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.