Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (95 page)

2.

Vertical:

a.

brain stem lesion

i.

upbeat nystagmus suggests a lesion in the floor of the fourth ventricle

ii.

downbeat nystagmus suggests a foramen magnum lesion

b.

toxic – phenytoin, alcohol (may also cause horizontal nystagmus).

Pendular

1.

Retinal (decreased macular vision) – albinism.

2.

Congenital.

SUPRANUCLEAR PALSY

Loss of vertical upward gaze and sometimes downward gaze. Clinical features (distinguishing from third, fourth and sixth nerve palsy):

1.

both eyes affected

2.

pupils often unequal

3.

no diplopia

4.

reflex eye movements (e.g. on flexing and extending the neck) intact.

STEELE-RICHARDSON-OLSZEWSKI SYNDROME (PROGRESSIVE SUPRANUCLEAR PALSY)

1.

Loss of vertical downward gaze first, later vertical upward gaze and finally horizontal gaze.

2.

Associated with pseudobulbar palsy, long tract signs, extrapyramidal signs, dementia and neck rigidity.

PARINAUD’S SYNDROME

Loss of vertical upward gaze often associated with convergence–retraction nystagmus on attempted convergence and pseudo Argyll Robertson pupils.

Causes of Parinaud’s syndrome

1.

Central:

a.

pinealoma

b.

multiple sclerosis

c.

vascular lesions.

2.

Peripheral:

a.

trauma

b.

diabetes mellitus

c.

other vascular lesions

d.

idiopathic

e.

raised intracranial pressure.

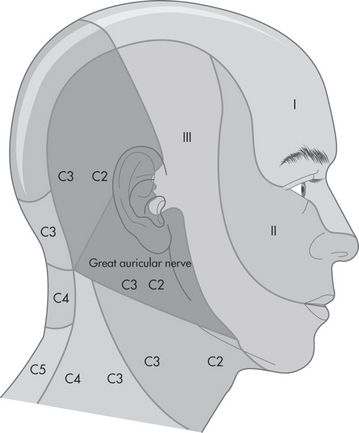

Fifth (trigeminal) nerve palsy (p. 410) (see

Fig 16.91

)

AETIOLOGY

Central (pons, medulla and upper cervical cord)

FIGURE 16.91

Divisions of the trigeminal nerve and dermatomes of the head and neck.

1.

Vascular.

2.

Tumour.

3.

Syringobulbia.

4.

Multiple sclerosis.

Peripheral (posterior fossa)

1.

Aneurysm.

2.

Tumour (skull base, e.g. acoustic neuroma).

3.

Chronic meningitis.

Trigeminal ganglion (petrous temporal bone)

1.

Meningioma.

2.

Fracture of the middle fossa.

Cavernous sinus (associated third, fourth and sixth nerve palsies)

1.

Aneurysm.

2.

Thrombosis.

3.

Tumour.

Other

1.

Sjögren’s syndrome.

2.

SLE.

3.

Toxins.

4.

Idiopathic.

HINT

1.

If there is loss of all sensation in all three divisions of the fifth nerve consider a lesion at the ganglion or sensory root.

2.

If there is total sensory loss in one division – consider a postganglionic lesion.

3.

If there is loss of pain but preservation of touch – consider a brain stem or upper cervical cord lesion.

4.

If there is loss of touch but pain sensation is preserved – consider a pontine nucleus lesion.

Seventh (facial) nerve palsy (p. 411)

AETIOLOGY

Upper motor neurone lesion (supranuclear)

1.

Vascular.

2.

Tumour.

Lower motor neurone lesion

1.

Pontine (often associated with nerves V, VI):

a.

vascular

b.

tumour

c.

syringobulbia

d.

multiple sclerosis.

2.

Posterior fossa:

a.

acoustic neuroma

b.

meningioma.

3.

Petrous temporal bone:

a.

Bell’s palsy

b.

Ramsay Hunt syndrome

c.

otitis media

d.

fracture.

4.

Parotid:

a.

tumour

b.

sarcoid.

CAUSES OF BILATERAL LOWER MOTOR NEURONE FACIAL WEAKNESS

1.

Guillain-Barré syndrome.

2.

Bilateral parotid disease (e.g. sarcoidosis).

3.

Mononeuritis multiplex (rare).

HINT

Myopathy and neuromuscular junction defects can cause bilateral facial weakness.

Eighth (acoustic) nerve (p. 411)

To differentiate nerve deafness from conductive deafness, use the following tests.

RINNE’S TEST

A 256-hertz vibrating tuning fork is first placed on the mastoid process, behind the ear and, when the sound is no longer heard, it is placed in line with the external meatus.

Results

1.

Normal – the note is audible at the external meatus.

2.

Nerve deafness – the note is audible at the external meatus because air and bone conduction are reduced equally, so that air conduction is better (as is normal); positive result.

3.

Conduction (middle ear) deafness – no note is audible at the external meatus; negative result.

WEBER’S TEST

A 256-hertz tuning fork is placed on the centre of the forehead.

Results

1.

Normal – the sound is heard in the centre of the forehead.

2.

Nerve deafness – the sound is transmitted to the normal ear.

3.

Conduction deafness – the sound is heard louder in the abnormal ear.

Note:

Although these tests are of traditional importance, they are not very accurate and are now rarely used by neurologists. However, candidates must be able to perform them.

HINT

The tines of the fork should be in line with the external auditory canal, so that the sound waves that leave the fork from two axes do not cancel each other out.

CAUSES OF DEAFNESS

1.

Nerve (sensorineural) deafness:

a.

degeneration (e.g. presbycusis)

b.

trauma (e.g. high noise exposure, fracture of the petrous temporal bone)

c.

toxic (e.g. aspirin, alcohol, streptomycin)

d.

infection (e.g. congenital rubella syndrome, congenital syphilis)

e.

tumour (e.g. acoustic neuroma)

f.

brain stem lesions

g.

vascular disease of the internal auditory artery.

2.

Conductive deafness:

a.

wax

b.

otitis media

c.

otosclerosis

d.

Paget’s disease of bone.

Ninth (glossopharyngeal) and tenth (vagus) nerve palsy (p. 411)

AETIOLOGY

Central

1.

Vascular (e.g. lateral medullary infarction owing to vertebral or posterior inferior cerebellar artery disease).

2.

Tumour.

3.

Syringobulbia.

4.

Motor neurone disease (vagus nerve only).

Peripheral – posterior fossa

1.

Aneurysm.

2.

Tumour.

3.

Chronic meningitis.

4.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (vagus nerve only).

Twelfth (hypoglossal) nerve palsy (p. 411)

AETIOLOGY

Upper motor neurone lesion

1.

Vascular.

2.

Motor neurone disease.

3.

Tumour.

4.

Multiple sclerosis.

HINT

The syndrome of bilateral upper motor neurone lesions of the ninth, tenth and twelfth nerves is called

pseudobulbar palsy

.

Lower motor neurone lesion – unilateral

1.

Central:

a.

vascular – thrombosis of the vertebral artery

b.

motor neurone disease

c.

syringobulbia.

2.

Peripheral (posterior fossa):

a.

aneurysm

b.

tumour

c.

chronic meningitis

d.

trauma

e.

Arnold-Chiari malformation

f.

fracture or tumour of the base of the skull.

HINT

The Arnold-Chiari malformation is a protrusion of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. The more severe types (II–IV) cause basilar compression with lower cranial nerve palsies, cerebellar limb signs (owing to tonsillar compression) and upper motor neurone signs in the legs.

Lower motor neurone lesion – bilateral

1.

Motor neurone disease.

2.

Arnold-Chiari malformation.

3.

Guillain-Barré syndrome.

4.

Polio.

HINT

It is difficult to detect unilateral twelfth lesions, as the tongue muscles (except the genioglossus) are bilaterally innervated.

CAUSES OF MULTIPLE CRANIAL NERVE PALSIES

Think of

cancer

first.

1.

Nasopharyngeal

carcinoma

.

2.

Chronic meningitis (e.g.

carcinoma

, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis).

3.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (spares nerves I, II and VIII), including the Miller-Fisher variant.

4.

Brain stem lesions – these are usually as a result of vascular disease causing crossed sensory or motor paralysis (i.e. cranial nerve signs on one side and contralateral long tract signs); patients with brain stem

gliomas

may have similar signs and may live for many years.

5.

Arnold-Chiari malformation.

6.

Trauma.

7.

Lesion of the base of the skull (e.g. Paget’s disease, large

meningioma

,

metastasis

).

8.

Rarely, mononeuritis multiplex (e.g. diabetes mellitus).

Higher centres

‘Please examine this 78-year-old man’s higher centres.’

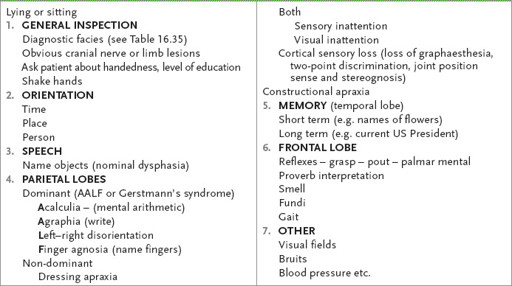

Method (see

Table 16.51

)

In this assessment especially, you must be guided by your findings. The introduction is important. For example, if you are told the patient also presents with right-sided weakness, you should concentrate on looking for dominant parietal lobe signs.

Table 16.51

Higher centres’ examination

1.

Shake the patient’s hand, noting any obvious focal weakness and introduce yourself. Explain that you will be asking him some questions.

2.

First, ask whether he is right- or left-handed. Then ask questions about orientation (person, place and time). Ask his name, the present location and the date.

3.

This also allows you to test for speech abnormality. Assess any nominal dysphasia by asking the patient to name some objects, such as your watch or a pen (see

Table 16.52

). Ask the patient to repeat a phrase or sentence, for example: ‘The barrister’s closing argument convinced him’. This allows you to assess the fluency of speech, as well as comprehension and repetition. Next ask the patient to perform one- and two-step commands, such as ‘point to the ceiling, but first take off your spectacles’. This assesses the patient’s comprehension.