Fenway Park (10 page)

Authors: John Powers

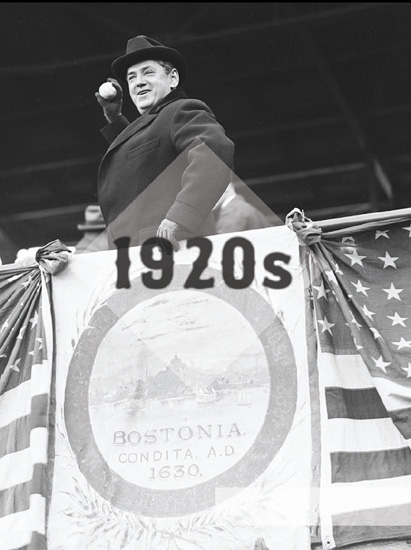

Fronted by the city’s official seal, Boston Mayor James Michael Curley threw out the first pitch at the 1924 home opener. The season was the sixth in a streak of 16 consecutive non-winning years for the Red Sox from 1919 to 1934.

A

s the Roaring Twenties progressed, those associated with the Red Sox must have kept telling themselves that it couldn’t possibly get worse—but it did, again and again. When the Fenway grandstand caught fire in May 1926, destroying a huge swath of seats, a

Globe

story said of team owner Robert Quinn, who had bought the club from Harry Frazee, “The Boston baseball public realizes what a difficult task he has had and has a world of sympathy for him.” There was no such sympathy for Frazee, who, upon selling Babe Ruth to the Yankees in January 1920, said of the New Yorkers, “I do not mind saying I think they are taking a gamble.” If it was a gamble, the Yanks hit the lottery several times over, as Ruth hit 54 home runs in his first season and led the team to six pennants in the 1920s alone. The trade was really just the first act in a continuous shunting of Boston’s talent to the Yankees by Frazee. For Quinn’s part, once he bought the club from Frazee in July 1923, he continued where Frazee had left off by making all the wrong moves. By 1923, the Sox didn’t have a single player remaining from their 1918 world championship team; and seven of those traded played for the Yankees in the 1923 World Series game that clinched New York’s first title. From the start, Boston fans flocked to Ruth’s return engagements at Fenway. On his first trip back, 28,000 turned out for a doubleheader; the

Globe

called it “one of the largest crowds . . . ever packed into the park for any game except a World’s Championship contest.” The story went on to say, “They saw what many of them went to see: the ‘Swatting Babe’ pole out a home run.” One wonders at what point the sight became tiresome.

T

he decade barely had begun when Harry Frazee made the deal that would be credited—and cursed—for elevating one franchise while eviscerating the other. “You’re going to be sore as hell at me for what I’m going to tell you,” the owner informed Manager Ed Barrow. “You’re going to sell the Big Fellow,” Barrow figured. The price for Babe Ruth was massive for the time—$100,000 from the Yankees, plus a $300,000 loan from New York owner Jacob Ruppert with Fenway Park as security. Frazee insisted that he would have preferred getting players in return, “but no club could have given me the equivalent in men without wrecking itself.”

While critics then and now claimed that Frazee wrecked his own club for more than a quarter-century, the fact was that the Sox already were headed south in the wake of their worst finish in a dozen years. For all his boisterous brilliance, Ruth hadn’t seemed likely to change that. “What the fans want, I take it, and what I want, because they want it, is a winning team,” said Frazee, “rather than a one-man team which finishes in sixth place.”

Although the reaction from many journalists and fans ranged from shock and depression to anger and betrayal, those feelings weren’t universal. “Men who have been in the baseball business generally conceded that Frazee was justified in making the sale,” James O’Leary wrote in the

Globe

. The sellee, however, complained he’d been made the goat for his former club’s failings. “I am going to return to Boston in the near future,” Ruth proclaimed in a telegram printed on the front page of the

Globe

, “and at that time the fireworks will start.”

But it was the Sox who provided the pyrotechnics for Ruth’s return, bashing New York, 6-0 and 8-3, in their Patriots Day doubleheader at Fenway and going on to win 10 of their first 12 games of the season. “I do not predict a pennant winner, but surprising things have happened in baseball and I may have a 1920 miracle crew in the present Sox,” said Barrow, whose club was in first place in late May. “Who knows?”

But when New York returned to sweep their hosts in four games just before Memorial Day, it was the start of a 4-14 slump during which Boston tumbled into fourth place and never recovered. Yet even without the Big Fellow, the Sox still managed a modest upgrade, finishing one place higher than they had the previous year. And Ruth remained immensely popular in the city where he’d made his name. More than 33,000 fans turned up for a “Babe Ruth Day” doubleheader on the Saturday of Labor Day weekend when the Knights of Columbus gave him a set of diamond cuff links between games, each of which Ruth punctuated with a home run.

The Hope Diamond itself wouldn’t have been enough to lure the man back to Boston, though, and his exodus was only the first in a procession of departures for the Bronx. Next was Barrow, who left after three years to become the Yankees’ business manager and one of the fiscal architects of what would become the game’s greatest dynasty.

Following him out the door before Christmas were pitchers Waite Hoyt and Harry Harper, second baseman Mike McNally, and catcher-outfielder Wally Schang. Thus continued what Boston faithful still call “The Rape of the Red Sox.” Then outfielder Harry Hooper, who thought he’d be offered the manager’s job instead of Hugh Duffy after wearing the uniform since 1909, departed for the White Sox. Hooper played in Chicago for another five seasons and went on to make the Hall of Fame. “One by one the old stars of the Red Sox leave us,” the

Globe

observed ruefully.

By then Boston undeniably was a second-division club. League president Ban Johnson pointedly ignored the Red Sox in his preseason evaluation for 1921 and only 7,500 fans turned up for the Fenway opener on April 21 to see the hosts blank the Senators, 1-0.

One of the season’s few home highlights was a mid-June sweep of the Tigers, punctuated by the ejection of the combustible Ty Cobb in the ninth inning of the finale. Cobb, who’d been arguing pitch calls from the on-deck circle, berated the umpire, dropped a bat on the arbiter’s foot, and then stepped on the man’s heels as he followed him around the plate and, as the

Globe

reported without specifying, “did things for which there was no justification whatever, and which led up to another incident as deplorable and more disgusting than anything that Cobb had done.”

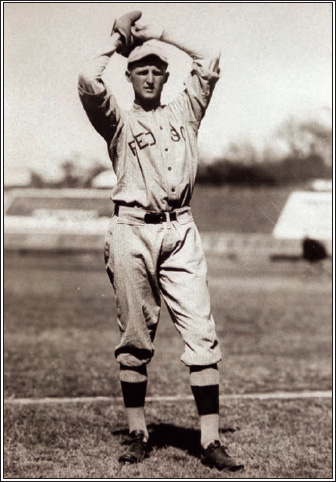

Herb Pennock won 240 games in the major leagues, and was part of two world championship teams with the Red Sox and four with the Yankees.

THE CURSE IS BORN

BY BOB RYAN

“Let me tell you this. You’re going to ruin yourself and the Red Sox in Boston for a long time to come.”

—Ed Barrow, Red Sox manager, when owner Harry Frazee told him he was selling Babe Ruth to the Yankees

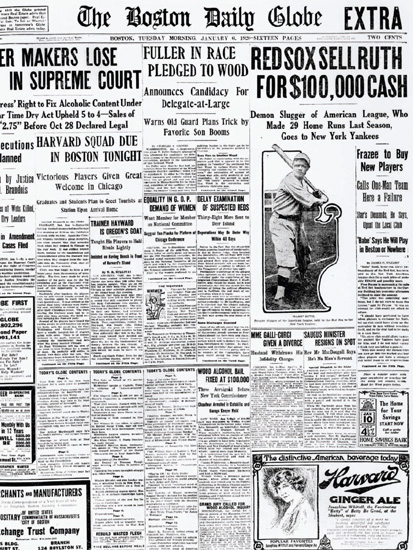

The shocking news was delivered in the dead of winter.

The good people of New England awoke on the morning of January 6, 1920, to discover that the most beloved baseball player in town was now a Yankee.

Thus was born “The Curse of the Bambino.”

Now, we all know there is no such thing. It is a whimsical hypothesis, the idea being that selling Babe Ruth was the equivalent of an original sin from which there can never be an absolution. Good throwaway line, that, and nothing more.

The truth is that it wasn’t just the sale of Ruth to the Yankees that plunged the Red Sox into the abyss (nine last-place finishes, a seventh and a sixth between 1922 and 1933), a situation that wasn’t remedied until Tom Yawkey bought the team and began spending tremendous sums of money.

It was the sale of Ruth and the subsequent sales and/or trades of catcher Wally Schang, shortstop Everett Scott, and pitchers Waite Hoyt, “Bullet Joe” Bush, “Sad Sam” Jones, and Herb Pennock to the Yankees that enabled the heretofore impotent team in New York to exchange places with the team that had been a four-time world champion between 1912 and 1918. When the Yankees clinched their first world championship by defeating the Giants in Game 6 of the 1923 Series, all seven played in the game.

That’s the crime. It wasn’t just the idea that owner Harry Frazee sold Ruth to the Yankees. It’s the complete package. What he did was provide New York with the complete foundation of a dynasty. Burt Whitman of the

Boston Herald

called it “The Rape of the Red Sox.”

But selling Ruth to New York was the hot-button move for all time. For as big as Ruth was in Boston, over the next 15 years in New York he became more than just a successful baseball player. He became a true American icon.

Sixty-five years after his last game, he remains the biggest baseball star of them all. He was the sports embodiment of the Roaring Twenties, swashbuckling his way through both American League pitching and life itself. No sports reality has galled Bostonians over the past 80 years as much as the fact that We created him and They—and not just any They but the most hated They of them all—reaped the full benefits, both short- and long-term.

People were upset at the time, of course, but the feeling wasn’t universal. The soon-to-be 25-year-old Babe was a highly flawed diamond. He was already starting to put on weight, he had a bad knee, and, most of all, he was a thoroughly undisciplined brat whose self-absorption, some said, was running the risk of harming the team. In fact, Frazee employed this last argument as a major rationale for selling his star, pointing out that despite Ruth’s individual heroics in 1919 (a record 29 home runs while leading the league in runs batted in with 114, runs with 103, and total bases with 284—all with the dead ball), the team had finished sixth.

Citing Ruth’s defiant behavior, which included missing the final game of the season in order to play a lucrative exhibition game in Connecticut, Frazee said, “It would have been impossible for us to have started the next season with Ruth and have a smooth working machine, or one that would have had any chance of being in the running.”

Baseball historians have spent the past eight decades debating the incident. Was Frazee in serious debt? Did he really, really need the $450,000 he received from the Yankees (there was also a $350,000 loan involved, with Fenway Park as collateral) in order to finance a Broadway musical called

No, No Nanette

? Or was he to be taken at face value when he said he had made a decision based on what he honestly believed to be in the best interests of the team? One thing is for sure: the musical in question didn’t open until 1925, so it wasn’t the catalyst for the trade.

Still, Frazee is hard to defend. Ruth was a handful, but rather than spend the Yankee money to acquire more talent, as he promised, all Frazee did was sell, sell, sell. The record is clear. The Red Sox hung on with fifth-place finishes in both 1920 and 1921, but in 1922 they took up what was almost permanent residence in the league basement for the next decade, as the Yankees, utilizing all the aforementioned Red Sox stars, were winning pennants in 1921, 1922, 1923, 1926, 1927, 1928, and 1932.

Despite his future success in New York, Ruth fondly recalled most of his time in Boston, where he first lived in Mrs. Lindbergh’s rooming house on Batavia Street (now Symphony Road); where he met his first wife, Helen Woodford, in a Copley Square coffee shop; where he bought an 80-acre farm in Sudbury in 1916; and where he became established as a star and a World Series hero.

As for Frazee, he left town on the midnight train for New York, a gesture of infinite symbolism for millions of Sox fans not yet born.