Fenway Park (8 page)

Authors: John Powers

With consecutive titles on his résumé and a world war on the boil, Lannin figured it was a propitious time to cash out, so he sold the club and the ballpark for $675,000 a few weeks after the season ended to theatrical men Harry Frazee and Hugh Ward. “I think I have turned over to the new owners the best team in the world,” Lannin said, “and it is now up to them to keep the champions at the top.”

With the same team back and Ruth coming into dominance, that seemed likely in 1917. While Ruth already was a gifted hitter—he hit two doubles and a triple to beat New York on Opening Day and also earned a win on the mound—his pitching was at least as notable. He won his

first seven games with what the

Globe

called “Ruthless warfare.” Then on June 23, he provided the unwitting prelude to Shore’s “perfect game” against Washington.

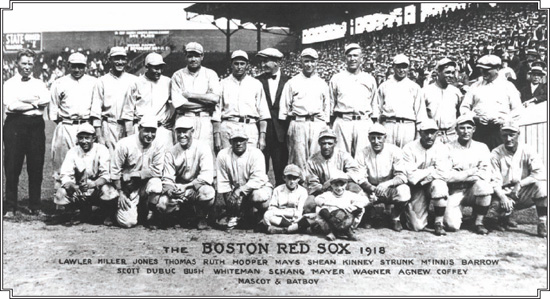

The 1918 Red Sox were led by Babe Ruth (back row, fifth from left), who won 13 games as a pitcher in his final season with the club and hit 11 home runs in a season abridged by World War I. The team defeated the Chicago Cubs in six games in the World Series.

After walking the first batter on four pitches, Ruth accused umpire Brick Owens of missing two of them. “Open your eyes and keep them open,” Ruth shouted. “Get in and pitch or I will run you out of there,” Owens replied. “You run me out and I will come in and bust you on the nose,” threatened Ruth, who proceeded to clock Owens and had to be dragged off by Jack Barry, the club’s new player-manager, and several policemen. On came Shore, who didn’t allow a Senator to reach base. “I don’t think I could have worked easier if I’d been sitting in a rocking chair,” he later recalled.

As expected, Boston’s pitching was superb, with Ruth winning 24 games and Mays winning 22. The club was in first place at the end of July. But punchless hitting did in the Sox down the stretch. “There is no use bewailing the fact that we cannot win this year,” Frazee concluded just before the Tigers swept his club at home in September.

So he sent a congratulatory telegram to counterpart Charles Comiskey after the White Sox won the pennant by nine games, and then turned down the sixth-place Braves’ offer of a consolation city series. “What Boston wants is a World Series and that is what the Red Sox are going after next season,” Frazee stated.

The Sox indeed were back in the Series in 1918, but amid dramatically altered circumstances. With America at war and “Work or Fight” the popular antislacker slogan, baseball was regarded as a frivolous pastime. Fenway attendance dropped from 387,856 to a record-low 249,513 in a season that was chopped to 126 games and ended on Labor Day. But after Frazee acquired first baseman John “Stuffy” McInnis, pitcher Joe Bush, catcher Wally Schang, and outfielder Amos Strunk from the penniless Athletics, his club was the class of a league that had been depleted by military enlistments. And Ruth, the game’s top slugger and an overpowering pitcher, undeniably was at the head of the class.

He was in fine shape after spending the winter chopping wood at his North Sudbury cottage. Ruth was an imposing woodsman at the plate that season also, hitting .300 and leading the league in homers and slugging percentage. “Just bust ’em,” he told the

Globe

, adding, “a base on balls is an obstacle on the path of progress. Take a good cut and bang that apple on the nose.”

When Ruth jumped the club in July after a clash with Ed Barrow, the new manager who was hired after Barry went off to the Navy, the issue was hitting—specifically, Ruth’s refusal to follow Barrow’s orders. “I got as mad as a March hare and told Barrow, then and there, that I was through with him and his team,” Ruth said. But he was back a few days later and it was his pitching that made the difference in the Series against Chicago.

“TESSIE” AND THE ROYAL ROOTERS

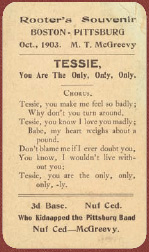

“Tessie,” a Broadway show tune written by William R. Anderson, became the theme song of the Boston fans known as the Royal Rooters when they followed the Red Sox to Pittsburgh in the first World Series in 1903. The Red Sox were seen as huge underdogs to the Pirates, and though the song had nothing to do with baseball, it seemed to provide luck to the Red Sox in important games. Perhaps it didn’t hurt Boston’s chances that the song was frequently reworded to cast aspersions on the talents, manliness, and parentage of their opponents.

The Red Sox won that first World Series, and in 1904 the Royal Rooters accompanied the team to New York for the final two games of the season. The Red Sox needed but one victory in the two games to capture the AL pennant, a situation that would recur in 1949. The Rooters, led by “Chief” Johnny Keenan, along with Michael “Nuf Ced” McGreevy and Jerry Watson, hired a band to accompany them, and they wrapped up the 1904 AL championship in the first game with the help of a wild pitch by the Highlanders’ ace, Jack Chesbro. Since the National League champion New York Giants refused to play the American League champion Red Sox, the Sox were declared unofficial world champions.

The song was reprised in the championship season of 1912, when the Red Sox christened Fenway Park with a World Series victory over the New York Giants. In 1914, the “Miracle Braves” borrowed Fenway for their home World Series games, and they swept the Philadelphia Athletics with the song as background. Over three more Series victories—in 1915, 1916, and 1918—Red Sox fans belted out “Tessie.”

Before the 1915 World Series, the Philadelphia “Nationals” stated their opposition to the Royal Rooters “assembling as one body” at the Series games hosted by Philadelphia. On October 2, Red Sox president Joseph Lannin traveled to New York on the midnight train to confer with American League President Ban Johnson.

Lannin said, “I will move heaven and earth to see that they are accorded the treatment to which they are entitled. . . . The Boston Royal Rooters are known all over the country for their loyalty and gameness, and are considered as much a part of a World’s Series in which a Boston team figures as are the players themselves. Whatever happens, the Royal Rooters and “Tessie” will have their accustomed places in the World’s Series setting.”

As a result of the negotiations, the Rooters received 400 seats for the Series games in Philadelphia.

As it turned out, the Red Sox hosted their own World Series games at Braves Field in 1915 and 1916 because the brand new park accommodated thousands more fans, and the more spacious playing field also played more to the Red Sox strengths of speed, pitching, and defense. The Red Sox drew more than 40,000 fans to four of their five home games in the two World Series and won all five games.

Late in the 1915 pennant race with the Detroit Tigers, a

Globe

story headlined “Old ‘Tessie’ Still on Job” began: “Maybe the presence of the Royal Rooters had nothing to do with the ultimate result, and maybe ‘Tessie’ did not figure at all in the Red Sox victory, but it is a matter of history nevertheless that the Rooters and their beloved ‘Tessie’ were there just the same—very much there—and that the Rooters and ‘Tessie’ have yet to trail with a losing Boston team.”

The story went on: “Three hundred loyal, lusty fans congregated on Commonwealth Ave. at the exit of the tunnel at 2:20, and at a word from Chief Johnny Keenan wended their way through the thousands of prospective spectators and again rendezvoused on Lansdowne Street, where the Royal Rooters’ band was ready to take up the strains of the wonderful baseball campaign song.”

They then marched to their customary position in the right-field bleachers, where they typically heckled the visiting teams while sunning themselves.

In April 1916, a

Globe

article noted that demand for Fenway box seats had more than doubled from any previous season, perhaps a testament to the team’s world championship the previous year. The Red Sox offered a 25-game ticket book for women at $12.50. Any number of the tickets could be used at any single game, and “the management expects that women will be more numerous at the games this season than ever before.”

Indeed, when the Red Sox made the 1916 World Series, the Royal Rooters under chairman John M. Killeen announced that for World Series games at the home of the Brooklyn team (then called the Robins, but soon to be the Dodgers), “special transportation arrangements for women with escorts” would be included, a feature not part of the planning since 1912. The rate for traveling fans for that World Series was $37, which included round-trip train transportation (parlor cars $2 extra), automobile transport to the park and back to the Elks’ Home at 43

rd

Street, pennants, souvenirs, and grandstand seats for five games, two in Brooklyn and three at home.

The Royal Rooters’ band of the time featured 30 pieces, though it was augmented for the World Series by 20 jubilee singers in Red Sox uniforms.

Michael “Nuf Ced” McGreevy’s 3rd Base Saloon, at Tremont and Ruggles Streets in Roxbury, opened in 1894. It was the principal

gathering spot for the Royal Rooters and is generally considered the first sports bar in the country, with both the South End Grounds and the soon-to-be-built Huntington Avenue Grounds a few blocks away. The saloon closed in 1921, shortly after Prohibition had outlawed the sale of alcohol in 1920. McGreevy’s bar got its name because it was the last stop before home for its patrons, and his own nickname reflected his habit of pounding his fist on the bar and announcing, “Nuf said,” when he decided that an argument between patrons need not escalate any further.

In 2008, Ken Casey of the Boston band the Dropkick Murphys (which reworked and reprised “Tessie” in 2004) and baseball historian Peter Nash opened McGreevy’s on Boylston Street, a tribute to the original bar and to Boston sports history.

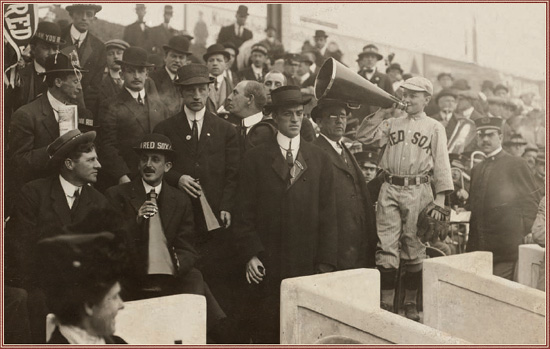

The Royal Rooters temporarily ceded the megaphone to Red Sox bat boy Jerry McCarthy during the 1912 World Series.

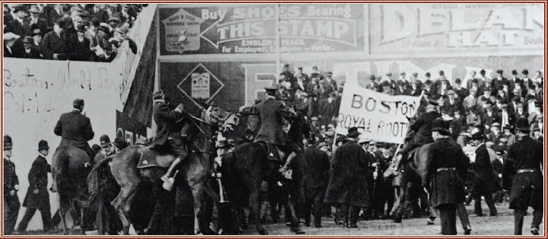

Baseball didn’t provide the only action on the field in 1912. Police had their hands full trying to push back Royal Rooters in the area known as Duffy’s Cliff, where temporary seats were a coveted World Series vantage point.