Fenway Park (7 page)

Authors: John Powers

LENDING AN EAR TO DE VALERA

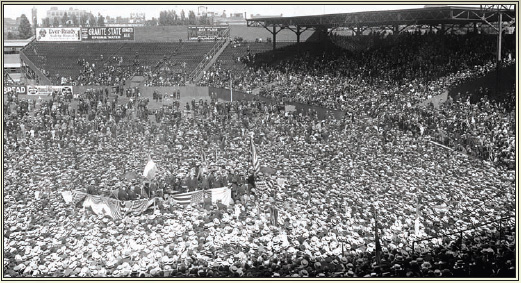

Eamon de Valera, president of the Irish Republic, came to America in 1919 to plead the cause of independence for the fledgling Irish state, and his visit to Boston brought a massive crowd of 50,000 to Fenway Park.

The

Globe

’s A.J. Philpott wrote, “It was an inspiring assemblage—one in which the spirit of the Irish people rose above the spirit of faction, of group or party.” Of the Irish president, he wrote, “The very mystery which attaches to this man, who was comparatively unheard of until recently, somehow fulfilled the dreams of the race—that some great figure would arise at the crucial moment and lead Ireland to freedom. In the thoughtful, militant, clean-cut face and gaunt personality of de Valera there is somehow also personified that new spirit which has come to Irishmen in which the demand has superseded the appeal for justice to Ireland. In that vast audience, you sensed this new dignity that has sunk into their consciousness.”

A large audience was expected, according to the

Globe

. But instead of 25,000, some 50,000 descended on the grounds. They filled the grandstand first, and then the wings on the right and left, and then they poured into the field and filled the space between the platform and grandstand—jammed it—then flowed around and backward in all directions, and there were thousands on the streets outside.

It was an ideal day for a great outdoor meeting—clear, sunny, and not too warm—and the location could not have been much improved. When a series of resolutions demanding the recognition of the Irish Republic were read, the unanimous “Ayes” could be heard over in Dorchester, and the silence that followed when the call came for the “Nays” led to a shout of laughter.

Some excitement was caused when three mounted policemen forced a passageway through the crowd to enable the committee, with President de Valera, to reach the speaker’s platform, which had been erected near home plate of the baseball diamond. On the whole, however, it was an orderly and patient audience. More than 20,000 members of the crowd stood from about 2 o’clock until after 5 o’clock, when “The Star-Spangled Banner” was sung and the audience dispersed quietly.

Two days later, as Eamon de Valera left New England for New York, he issued a message thanking the people of the region: “I did not need to come to Boston or to America to know that Americans would not lend themselves to an act of injustice against an ancient nation that clung to its traditions and maintained its spirit of independence through seven centuries of blood and tears. In the name of Ireland, I thank you.”

By June 25, when the pennant finally was raised before a chilled crowd of only 6,500, the Sox were only in fifth. In mid-July, McAleer replaced Stahl, who’d played only two games due to a foot injury, with catcher Bill Carrigan. A player-manager who couldn’t play wasn’t much good, especially one who was rumored to want his job, McAleer reckoned. But the burly Carrigan, known as “Rough” for his rugged play behind the plate, couldn’t pull his mates out of their hole and they finished fourth, more than 15 games behind Philadelphia. With no world championship to contend for, the Sox challenged the Braves to a best-of-seven series. But their crosstown neighbors begged off because a couple of their key players were hurt.

There would be another World Series at Fenway in 1914, but it would be the Braves acting as hosts after they staged the greatest comeback in the sport’s young history. The threadbare neighbors hadn’t had a winning season since 1902, when they were the Beaneaters, and had since changed their name three times. On July 18 they were in last place, 11 games behind the Giants. Then, guided by Manager George “Miracle Man” Stallings, the Braves went on a relentless hot streak, winning 59 of their final 75 to claim the pennant by 10½ games.

By early August, their revival had attracted so much attention that their home, South End Grounds, which seated only 5,000, was being overrun. So Sox owner Joseph Lannin, who’d bought the franchise during the preceding winter, offered the Braves the use of Fenway for the rest of the season. His own club was a distant second to the Athletics by then, but its renaissance already was underway in the form of pitcher George Herman Ruth, a 19-year-old son of a Baltimore saloon owner the

Globe

described as “one of the most sensational moundsmen who ever toed a slab in the International League.”

Lannin, who’d emigrated from Quebec and started as a hotel bellboy, had made his fortune in real estate and commodities. He saw rare potential in the raw and untutored Ruth, bought him from the minor-league Orioles with Ben Egan and Ernie Shore for a reported $25,000 (give or take several thousand, depending on your source), and promptly put him in uniform. But the Sox couldn’t catch the Athletics, who went on to play the Braves in the World Series.

By then even the Royal Rooters had switched allegiances. The town was entranced—73,000 people had turned out for a separate-admission Labor Day doubleheader between the Braves and the Giants, with another 10,000 turned away. And nearly 70,000 showed up for the final two games of the Series as the Braves sealed the first sweep in World Series history with 5-4 and 3-1 victories. “There was joy last night in Boston,” said the

Globe

editorial, “the land of the free and home of the Braves.”

The Braves’ days as a glorified Twilight League team, playing in a sandlot at the corner of Walpole Street and Columbus Avenue, were over. Owner James Gaffney was building a capacious new park between Commonwealth Avenue and the Charles River that had foul lines of more than 400 feet and a distance of 440 to dead center and that seated better than 40,000.

PERFECT RELIEF FOR RUTH

Ernie Shore was acquired by the Red Sox in the same deal that brought them Babe Ruth in 1914. Shore became an outstanding pitcher for the Red Sox, going 19-8 with a 1.64 ERA in the 1915 world championship season, and winning 16 more games the following year when the Sox repeated as world champs. He even pitched a three-hitter in the title-clinching victory. However, Shore is forever linked with Ruth and best known for his performance in one of the oddest games in baseball history.

Shore was in the dugout on June 23, 1917, two days removed from a pitching outing when Ruth started on the mound at Fenway against the Washington Senators. Ruth walked the leadoff hitter, Ray Morgan, but his gripes with the strike zone were immediate and forceful. He complained to plate umpire Brick Owens repeatedly, and after the ball four call, Ruth and Owens met in front of the plate, where Ruth apparently threw a punch at Owens. Along with Sox catcher Chet Walker, Ruth was ejected and later received a 10-game suspension, and the Red Sox were now short a pitcher.

Shore came on in relief, getting only five warm-up throws according to the rules of the time. No matter, Shore thought, he would be replaced once another pitcher had sufficient time to warm up. Morgan was quickly caught attempting to steal second by new catcher Sam Agnew, and Shore went on to retire batter after batter after batter—26 in a row after the man was caught stealing, to complete a Red Sox no-hitter. In fact, Shore got credit for a perfect game for more than 70 years, before a baseball committee ruled in 1991 that it couldn’t be regarded as a perfect game, since Shore hadn’t started it.

Shore, who retired with 65 victories in seven seasons, went on to become a county sheriff in North Carolina, and he enjoyed the notoriety of his distinctive performance. He died in 1980, before his status as a perfect-game pitcher was downgraded to a combined no-hitter.

“Practically everyone has heard of me,” Shore told

Sports Illustrated

in 1962. “People are always asking me about that game. I can’t say I really mind.”

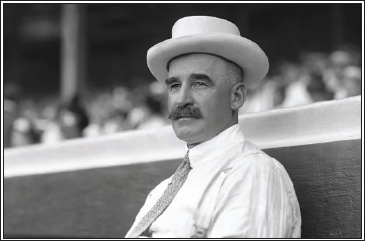

Real estate tycoon Joseph Lannin became sole owner of the Red Sox in 1914. He brought Babe Ruth to Boston, which helped the club capture World Series wins in 1915, 1916, and 1918. Lannin sold the team to Harry Frazee in 1917, setting the stage for The Curse.

That was considerably more than Fenway could accommodate, so the Sox were content to accept the Braves’ offer to use their new playpen for the 1915 World Series. In case Carrigan and his teammates needed an added incentive, they had to stand and watch the Athletics raise the 1914 pennant on Opening Day at Shibe Park. Though injuries hobbled them early—the Sox were in fourth place at the end of May—their superior pitching eventually came into play. “I still believe, as do most of the other players in the circuit, that Boston is the really dangerous club,” Tigers star Ty Cobb said in the

Globe

on June 27.

After sweeping three home doubleheaders in three days from the Senators in early July, the Sox were on the move and by July 19 had taken over the lead from Chicago. By then the Braves were making another surge up from the cellar and for a couple of months the city was daydreaming about a Trolleycar Series, but the defending champions couldn’t catch the Phillies.

The Sox essentially had wrapped things up by September 20 after taking three straight at home from the Tigers to go up by four games. “Goodby, Ty Cobb. You failed to show,” taunted the

Globe

. Before they went on the road for the final seven games of the season, the Sox practiced for three days at Braves Field to get a feel for its supersized dimensions and found them suitable, if initially strange.

By the time the club faced the Phillies in the Series, it found its temporary autumnal home quite comfortable. Sox pitchers Dutch Leonard and Ernie Shore each baffled the visitors by 2-1 counts to give the Sox a 3-1 Series advantage. As it turned out, the Fens would have been overrun by the crowds, which numbered 42,300 and 41,096 for the two games at Braves Field, with thousands still outside when the gates were locked. When Boston closed out the Series in Philadelphia, it marked the beginning of a mini-dynasty, with three championships in four years.

Though he could have raised ticket prices in the wake of the championship, as most clubs do, Lannin actually lowered them for 1916, reducing a box seat from $1.50 to $1 and all but the first five rows of the grandstand to 75 cents. But even with Wood sitting out the season and Speaker dealt to the Indians, the Sox managed to repeat behind an extraordinary pitching staff. Ruth, who outdueled Washington legend Walter Johnson four times, posted a 23-12 mark, followed by Leonard (18-12), Carl Mays (18-13), Shore (16-10), and Rube Foster (14-7).

For the only time in franchise history, two Sox pitchers threw no-hitters at Fenway in the same season. “The Broadway tribe had about as much chance of getting a base knock off the Oklahoma farmer as they have of changing the situation in Mexico,” the

Globe

reckoned after Foster blanked New York, 2-0, on June 21. By the time Leonard squelched St. Louis, 4-0, on August 30, Boston was firmly in first place. “Their specialty for two years now has been beating pennant rivals in the pinch,” Grantland Rice wrote in the

Globe

. “Their favorite dish is Crucial Series, frapped.”

After the Sox held off Chicago by two games for the pennant, they returned to Braves Field for a World Series date with the Brooklyn Robins (as the Dodgers then were known). After Ruth stifled the visitors for 14 innings before 41,373 in the second game, it was clear that Boston had a bird in hand. “Only a Miracle Can Stop Sox,” the

Globe

declared after a 2-1 victory put them up two games going back to Brooklyn. When the Sox split there, it was left to Shore to stifle the Robins, 4-1, for the crown at home. Boston, Rice proclaimed, was “the unconquered citadel of the game.”