Fenway Park (4 page)

Authors: John Powers

He didn’t want freeloaders sneaking into the standing areas in the outfield or peering down from nearby rooftops, so he erected a 25-foot wooden wall that he could cover with paid advertisements and that was buttressed by a 10-foot incline that made fielding fly balls something between art and accident.

Red Sox team president John I. Taylor, whose father was principal owner of the Globe, sold half of the Red Sox and built Fenway Park on land that he owned in the newly developed Fenway section of the city.

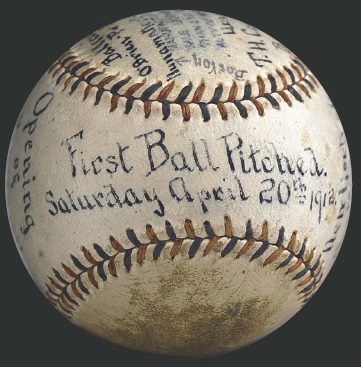

The first ball put into play in the first game at Fenway Park, with an inscription by umpire Tom Connolly.

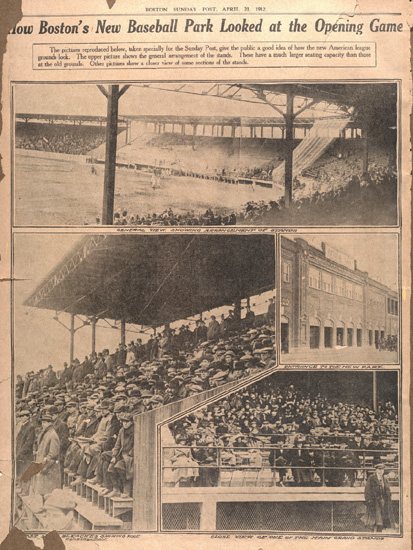

The

Boston Post

ran several photos of the new ballpark the day after the Red Sox defeated the New York Highlanders, 7-6, in 11 innings, in the park’s inaugural game.

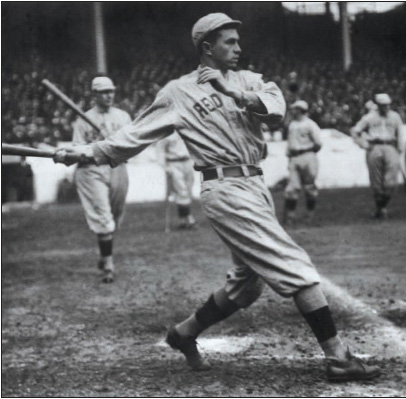

Hall of Fame outfielder Harry Hooper is the only man to play on four Red Sox world championship teams.

Although the foundation was designed to support an upper deck, Taylor wanted his $650,000 playpen finished in time for the 1912 season, which left only seven months from the September groundbreaking. So a grandstand was built to hold 15,000 ticket holders with additional seating along the lines. Quartets of box seats were offered at $250 for the season, with pavilion seats going for 50 cents a game and bleacher spaces for 25 cents.

Fenway Park was such a novelty and the April weather so inhospitable that what the

Globe

called “the real down-to-the-book official dedication with the music stuff, the flowers and the flags” did not occur until May 17, when the Sox lost to Chicago, 5-2, after leading 2-1 until the ninth, before 17,000 fans. Only 3,000 witnesses had turned out for the dress rehearsal on April 9, a 2-0 exhibition game victory over Harvard that was played amid snow flurries. “It was no day for baseball,” the

Globe

concluded. Nor were April 18 and Patriots Day, when the scheduled league opener and rescheduled doubleheader were rained out.

When the sun finally appeared on April 20, more than 24,000 fans were on hand for the first official game and what would, in later decades, become a celebrated rarity—a victory over New York, this one achieved in 11 innings by a 7-6 count.

It took another four games for a ball to be knocked over the left-field wall, which then was more of a barrier than a monster. The man who did it, reserve first baseman Hugh Bradley, had hit only one other homer in his career and never managed another. But after sitting on one of southpaw Lefty Russell’s corkscrew curves, Bradley lashed “a terrific smash” over the fence for a three-run shot that gave the Sox a 7-6 victory over the Athletics. “The scene that followed was indescribable,” Tim Murnane wrote in the

Globe

. “Spectators jumped onto their seats and threw their hats in the air and howled like Indians until Bradley had ducked out of sight, with the Boston players offering congratulations.” The Sox quickly proved themselves capable of running up dizzying numbers. “SWAT! SWAT! SWAT!” read the

Globe

headline after the “Speed Boys“ outgunned Washington, 33-19, in a May 29 home doubleheader, with the scorers for both clubs covering over three-and-a-half miles (“Hitting and Run-Getting on Wholesale Basis at Fenway Park”). On June 29, rain washed out the game with New York with Boston leading, 10-0, with two out in the first inning. But the hosts won, 8-0, the next day.

By July 20, when the club was in first place by seven games over the Senators, the

Globe

essentially awarded it the pennant with this headline: “Keen Head Work Combined With Acutely Schemed Team Play; Excellent Pitching, Catching, Infield and Outfield Action; Timely Hitting and Shrewd Base Running Have Shined Gloriously Bright the Outlook for Winning the 1912 Championship.”

Howard “Smoky Joe” Wood, the game’s best “twirler,” went an astounding 34-5 for the Sox in 1912, while his teammates Buck O’Brien and Hugh Bedient each won 20 games. Tris Speaker batted .383 and Duffy Lewis knocked in 109 runs. The Sox didn’t even have to clinch the pennant on their own. When they were being rained out in Cleveland on September 18, the White Sox beat the Athletics to give Boston its first American League title since 1904. By then management had already begun expanding Fenway’s capacity to 32,000, adding 900 box seats and new stands in left and right field.

“The game was full of interest, the crowd holding its seats to the end, figuring that the Red Sox would eventually nose out the Broadway swells.”

—T. H. Murnane,

Boston Globe,

April 21, 1912, in a

story headlined “Sox Open to Packed Park”

BACK IN THE DAY

BY JOHN POWERS

The Red Sox began the 1912 season with a new brick-and-steel ball yard (“the mammoth plant with the commodious fittings”) and no ghosts. Their fifth-place finish in 1911 had been forgotten. By the time they hosted the New York Highlanders on April 20, a sunny Saturday afternoon, they were already sitting in first place in the eight-team American League, well on the way to the finest year in club history (105-47 and the world championship over the New York Giants).

J. Garland “Jake” Stahl, the new player-manager who worked as a Chicago banker in the off-season, had promised no less. The Red Sox, he said, would give the Boston public “only the best of baseball this season, barring accidents.”

“It will be good to play some baseball,” Stahl said. “We have come out of Hot Springs [Arkansas] ready to go. We started well and we do not need any more postponements.”

The Red Sox were 4-1 after wins in New York and Philadelphia on the way north. The visiting Highlanders had not liked sitting around in their hotel—the Copley Plaza—for extra, wasteful days.

Opening Day was perhaps something of an anticlimax. Fenway Park, which replaced the old Huntington Avenue Grounds, actually had been opened and used 11 days earlier when 3,000 customers shivered amid snow flurries while the Red Sox shut out Harvard in an exhibition. The game with the Highlanders (now Yankees) had been postponed by two days of rain, from Thursday to Saturday. And most people were preoccupied with the

Titanic

, which had sunk on Monday morning with several dozen New Englanders aboard.

The Boston-New York game was listed on the amusements page of the newspaper, merely one of several urban attractions that day. Billie Burke was playing in

The Runaway

at the Hollis Street Theatre. There was a Taft rally at Faneuil Hall, the Textile and Power Show at the Mechanics Building (admission 25 cents), the BSO at Symphony Hall. And at the Park Theatre,

Hoopla! Father Doesn’t Care!!

If you wanted to attend Opening Day, you could buy a reserved seat in the grandstands for 75 cents or a bleacher seat for a quarter. Tickets were available at Wright and Ditson at 344 Washington Street or at the gate. The ballpark was packed with 24,000 spectators, with hundreds of them standing behind a rope in the outfield. Yet attendance for the season would total only 597,000.

The Sporting News

predicted that the park would become more popular when people got accustomed to “journeying in the new direction.”

If you owned a car in 1912, you could park it almost anywhere you pleased near the ballpark. The only two buildings near the park were a riding school and a garage out beyond right field. The West Fens was terra nova at the time. Artists, students, musicians, and assorted bohemians lived there, out beyond the water and marsh. Speculators owned the land, looking to sell it to developers who would erect apartment buildings near the trolley lines.

Most of the Opening Day crowd arrived by public transit, taking the Ipswich Street, Beacon Street or Commonwealth Avenue cars and walking past open lots to the park. A cadre of “big, fine-looking officers” from Division 16 preserved order. Inside the park customers drank Pureoxia ginger ale, Dr. Swett’s Original Root Beer, and cold lager. If Fenway Franks were available, it was not recorded.

Mayor John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald (the future maternal grandfather of President John F. Kennedy) tossed out the first ball, with Governor Eugene Foss at his side, and Buck O’Brien threw the first pitch at 3:10 p.m. “There was no time wasted in childish parades,”

Globe

writer T.H. Murnane observed. The boisterous Royal Rooters, led by South End saloonkeeper Michael T. “Nuf Ced” McGreevy, serenaded the assemblage with their theme song, “Tessie.”

The Red Sox, also called the Speed Boys, climbed out of a 5-1 hole and won, 7-6, in 11 innings, helped by five hits, including a pair of doubles, by second baseman Steve Yerkes. Murnane wrote, “Tristram Speaker, the Texas sharpshooter, with two down in the 11

th

inning and Yerkes on third, smashed the ball too fast for the shortstop to handle and the winning run came over the plate . . . the immense crowd leaving for home for a cold supper but wreathed in smiles.” The size of the crowd may have hindered the Red Sox cause, said Murnane. “Before the game, the crowd broke into the outfield and remained behind the ropes, forcing the teams to make ground rules, all hits going for two bases. This ruling was a big disadvantage to the home team, for the Highland laddies never hit for more than a single, while three of Boston’s hits went into the crowd, whereas with a clear field they would have gone for three-base drives and possibly home runs, and would have landed the home team a winner before the ninth inning.”

The writers finished up their scorecards promptly at 6:20 and went back to Newspaper Row. Nobody bothered entering the clubhouse to talk to the players.