Fenway Park (2 page)

Authors: John Powers

“The ballpark is the star. In the age of Tris Speaker and Babe Ruth, the era of Jimmie Foxx and Ted Williams, through the empty-seats epoch of Don Buddin and Willie Tasby and unto the decades of Carl Yastrzemski and Jim Rice, the ballpark is the star. A crazy-quilt violation of city planning principles, an irregular pile of architecture, a menace to marketing consultants, Fenway Park works. It works as a symbol of New England’s pride, as a repository of evergreen hopes, as a tabernacle of lost innocence. It works as a place to watch baseball.”

—Martin F. Nolan, former Boston

Globe

editorial page editor

| Foreword | CONTENTS |

| Special Introduction | |

| Introduction | |

| 1910s | |

| 1920s | |

| 1930s | |

| 1940s | |

| 1950s | |

| 1960s | |

| 1970s | |

| 1980s | |

| 1990s | |

| 2000s | |

| Photography Credits | |

| Index |

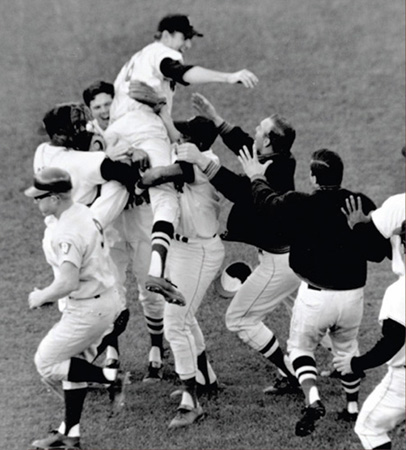

On the final day of the 1967 season, teammates and fans rushed Jim Lonborg after he pitched the Red Sox to victory over the Minnesota Twins to gain at least a tie for the American League pennant.

I

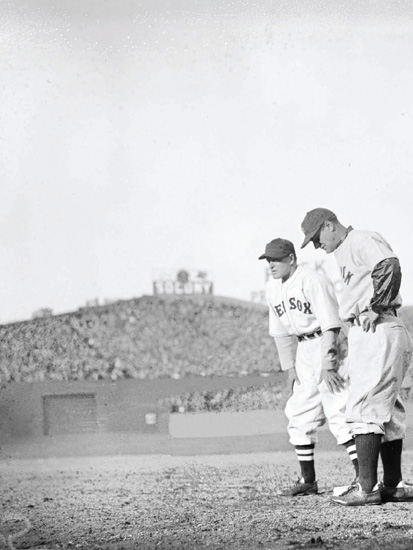

first saw Fenway Park in 1965 when I was a rookie pitcher for the Red Sox. We had played a couple of exhibitions on the way home from spring training in Scottsdale, Arizona, and had flown into Boston on Saturday night. We were staying at the Kenmore Hotel and we walked over for a workout on Sunday. I was used to ballparks like Candlestick Park and Dodger Stadium in California, so it was unique to be in a city setting and enter through a beautiful brick facade.

I remember coming through the tunnel on the first-base side and the first thing I saw was the Wall. I thought, this is where I have to work? I stepped off the distance from home plate to the Wall to see whether the posted distance of 315 feet was an accurate reading and it wasn't. But our coaching staff did a really good job of preparing us mentally to pitch in Fenway. The Wall can help you as much as it hurts you because a lot of line drives are knocked down by it. Since I was a sinkerball pitcher, if balls were up in the sky I wasn't making very good pitches.

My first major-league victory came in Fenway against the Yankees on May 10. It was a thrill to pitch against Mickey Mantle, who'd been one of my boyhood heroes, and I struck him out in his first at-bat. After that, though, he had a single and a homer, and when Mickey hit a double with two out in the ninth Billy Herman, our manager, came out and said, “I think it's time to bring in the Big Guy.” So Dick Radatz came in for the save and we won 3-2.

There weren't many fans at our games during my first two years and sounds travel very well at Fenway so you could hear what players and fans were yelling. But in 1967 after we won 10 in a row and returned from that road trip, we came back to packed seats. People still tell me that it was the greatest summer of their lives. None of us ever had been in a pennant race before. That year we had four teams involved—the Twins, White Sox, Tigers, and us—and you couldn't help but scoreboard-watch. At Fenway we had the best way of keeping score—the guy in the Wall. You would see that number disappear and wait for the next one to come up. It wasn't like it was being blurted out on a Jumbotron. You'd be in a situation where you wouldn't be expecting a cheer and you'd turn around and look at the scoreboard.

That final game against Minnesota was so tense all the way through. To make the comeback we did, to be on the field at the end and celebrate with all the players and then to turn around and see thousands of fans coming onto the field was the most exciting moment of my life. It was something a little kid would think about when he was a make-believe pitcher.

But as the fans were carrying me on their shoulders, the feeling went from jubilation to a little bit of fear. I was going places where I didn't want to go, out by Pesky’s Pole. Finally the police got me to where I wanted to go, which was the clubhouse, where we still had to wait for the Angels-Tigers game to end in Detroit. For us to be sitting around a radio instead of a TV, it reminded me of an old-time movie where you were listening for news of some important event.

After the Angels beat the Tigers and we'd won the pennant, I went upstairs to see Mr. Yawkey to give him the game ball that my teammates had given to me. I knew that it was such a long time since he'd had anything good like that happen for him that I thought he should have it. It was almost like the owner's office in

The Natural

, with the dark hallway and the dark-paneled room. Mr. Yawkey was there and I gave him the ball. He cried a lot that day. That was a special chapter of a fabled story. The beauty of the Red Sox is that every year is a different chapter—and there's still more to this book.

Whenever I come back to Fenway I try to go in through the same ramp that I did that first time in 1965, and it's the same feeling. It has so many great memories for me. The greenness, the majesty of the Wall. That image never goes away.

Jim Lonborg was the first Red Sox pitcher to win the Cy Young Award (1967)

A

fter the death of my father, John I. Taylor, in June of 1987, I had to clean out his office at the

Boston Globe

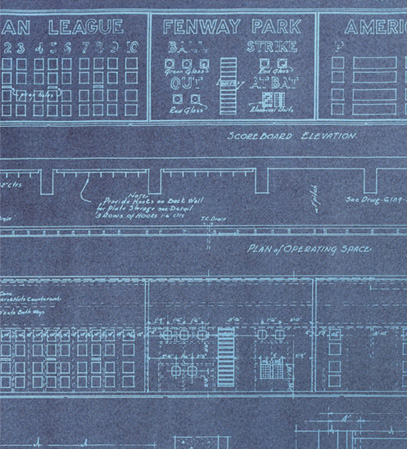

, where he had spent more than five decades as a newspaperman. Most of what I found was unremarkable, with one exception. In the dark recesses of a closet, I discovered a couple of blueprints. One was of Fenway Park and the other a detailed sketch of the hand-operated scoreboard still extant on the park’s left-field wall. Upon closer inspection, I realized that the blueprints were of the renovation of the park in 1933 by then-owner Thomas A. Yawkey. I assumed that they were given to my father because his father, also named John I. Taylor, is credited with having built Fenway Park.

I never met my grandfather. He died in 1938, ten years before I was born. I was vaguely aware—no doubt from reading the great Peter Gammons—that he was the president of Boston’s American League franchise from 1904 to 1911, that he changed the name of the team from the Boston Americans to the Boston Red Sox, and that he built Fenway Park. Other than this, I knew very little about him. Conversations with my older brothers confirm that our father rarely talked about his father. I cannot deny feeling a bit of family pride around his connection to Fenway Park, but I am also aware that my grandfather was thoroughly trashed as a meddlesome owner and dilettante by Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson in their book

Red Sox Century

.

I hung the blueprints in my office at the

Globe

and then at home after I left the paper in late 1999. When I discovered they were fading because of exposure to the light, I took them off the wall and stored them in our attic where they now reside, gathering dust. (You can see them, restored to their original blue, at left and on the next page.)

As a fan, my experience is not unlike thousands of others in New England. In the first game I can remember attending at Fenway, the Red Sox played the great 1954 Cleveland Indians team that won 111 games during the 154-game regular season. I was seven years old. That same decade, I remember my parents telling me I couldn’t go to a game with the rest of the family because of the polio scare. Like many Red Sox fans of a certain age, I was thrilled by the magical seasons of 1967, 1975, and 1986, when the Sox came within one game of winning the World Series and breaking the Curse of the Bambino. I became addicted to reading newspapers when I was young because of the Red Sox coverage. To this day, Sox stories in the

Globe

remain one of the first staples I turn to each morning.

On my office wall now, I have a picture of Ted Williams and his beautiful swing during the All-Star Game in 1946. On the same wall, near the

Globe

front page of August 9, 1974 announcing Nixon’s resignation, is a framed reproduction of the

Globe

’s front page of October 28, 2004 chronicling the Sox victory in the World Series for the first time since 1918. Like many Red Sox fans, I feel we are extremely fortunate that the current ownership chose to improve Fenway rather than build a new park. They have preserved a national treasure. That choice seems to have been a good business decision too, as the Sox continue to draw extraordinary crowds for home games.

My mother was a consummate Red Sox fan. She used to listen to games on the radio. Curt Gowdy’s mellifluous tones and then Ned Martin’s were familiar sounds in my house growing up. Born in 1915, which made her too young to remember the championship seasons of that year, 1916, and 1918, my mother used to say her one wish was that the Red Sox win a World Series before she died. She died in 1990, missing the championships of 2004 and 2007 that finally ended the club’s long stretch of futility.

There is no way to predict the future, or how long Fenway will survive into the 21st century. It is important not to stay stuck in the past. Fenway, though vastly improved in recent years, is not without flaws. The right-field grandstand seats have lousy sightlines that apparently are very difficult to improve. Legroom is not the park’s strongest suit. Many of the best seats have become financially prohibitive. Nevertheless, as it celebrates its 100

th

anniversary, the park still works remarkably well as a place where fans can enjoy professional baseball at the highest level. Those of us who love the game can only hope that Fenway Park remains an essential part of the soul of New England and of the national pastime for a long time to come.

Benjamin Taylor is a former publisher of the

Boston Globe