Fenway Park (3 page)

Authors: John Powers

Blueprint of Fenway Park dated January 8, 1934. It was found in the Boston

Globe

office of the late John I. Taylor, along with a blueprint of scoreboard renovations (page 16) dated October 25, 1933. Images restored and reproduced (see pullout poster) courtesy of the Taylor family.

T

he storied home of the Red Sox for a century, “America’s Most Beloved Ballpark” also is the oldest in the major leagues, and the most famous. From the classic brick entrance on Yawkey Way, to the unique left-field wall with its manual scoreboard, to Pesky’s Pole in right field, its timeless features are recognized from the Bronx to the Dominican Republic to Japan.

John Updike’s “lyric little bandbox,” which he likened to “an old-fashioned peeping-type Easter egg,” is so linked with Boston and baseball history that it is a destination in itself, equal to the Freedom Trail and the swan boats, with visitors taking guided ballpark tours even during winter. In

Cheers

, the long-running situation comedy based in a Back Bay tavern, bartender Sam “Mayday” Malone was a former Red Sox relief pitcher. The fan film

Fever Pitch

is based around Fenway. It is also where Kevin Costner took James Earl Jones for an inspirational outing in

Field of Dreams

.

Fenway’s field is like no other. Because the park was jammed into a city lot bounded by narrow streets, its dimensions are a crazy confluence of oblique angles—like the three-sided oddity in center field that can turn the game into Pachinko, with the ball bouncing and rattling about. There is so little playable foul territory that dozens of balls end up in the stands, which are so close to the diamond that fans can hear the players’ chatter.

Fenway is a charmingly auditory experience, from the scalpers on Brookline Avenue (“Who needs tickets?”), to the fans singing “Sweet Caroline” during the eighth inning, to the playing of “Dirty Water” over the public address system after victories.

Fenway’s endearing quirkiness is the key to much of its allure. Except for some increased seating and creature comforts, the park has remained largely unchanged since it opened in 1912 in the same week that the Titanic sank.

“When I brought my kids to Fenway, they never complained about the inconveniences of the ancient ballpark,” wrote

Boston Globe

columnist Dan Shaughnessy, who confessed that he still took “some weird comfort in the knowledge that the poles that occasionally obscured our vision of the pitcher are the same green beams that blocked the vision of my dad and his dad when they would take the trolley from Cambridge to watch the Red Sox in the 1920s.”

Babe Ruth threw his first pitch and Ted Williams hit his last home run at Fenway. From Christy Mathewson, to Ty Cobb, to Satchel Paige, to Joe DiMaggio, to Hank Aaron, most of baseball’s greatest names have appeared on Fenway’s stage, which also has accommodated an extraordinary variety of other athletes, politicians, and entertainers.

Three of Boston’s professional football teams—the Redskins, the Yanks, and the Patriots—performed at Fenway. The Bruins and Flyers, two of hockey’s fiercest rivals, played in the Winter Classic there on New Year’s Day. Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave his final campaign address at Fenway. The Rolling Stones, Stevie Wonder, Paul McCartney, and Bruce Springsteen all sang there.

Through it all the

Boston Globe

has been the consistent, respected chronicler—both in words and in pictures—of every important event in Fenway’s history. The Taylor family, the newspaper’s founders and longtime stewards, owned and named both the team and the park. So it’s appropriate that the

Globe

has produced the definitive book celebrating 100 years of Fenway Park, a collector’s item featuring exceptional writing and unforgettable images from the

Globe

’s incomparable archive of photographs, illustrations, and front pages.

Every significant moment from every year is here, and then some. The dramatic World Series victory over the Giants in 1912. The 1934 fire that scorched Tom Yawkey’s renovated park. Ted Williams’s “Great Expectoration” of 1956. Jim Lonborg’s “hero’s ride” after putting the Sox in position to secure the Impossible Dream pennant in 1967. Carlton Fisk’s dramatic, “is-it-fair?” homer in the 12

th

inning of Game 6 of the 1975 World Series against the Reds. Bucky “Bleeping” Dent’s heartbreaking screen shot in the 1978 divisional playoff game with New York. Roger Clemens’s record 20 strikeouts against the Mariners in 1986. Dave Roberts’ stolen base against the Yankees in 2004 that was the beginning of the end of 86 years of October frustration.

Fenway is all about lore. The Royal Rooters torturing visiting ballplayers with incessant renditions of “Tessie.” Williams’s monster bleacher shot knocking a hole in a fan’s straw hat. Manny Ramirez’s mystery disappearance inside the belly of the Monster. Jimmy Piersall oinking like a pig on the base paths. Luis Tiant’s rhumba windup that the

New Yorker

’s Roger Angell dubbed “Call the Osteopath.” Pedro Martinez playing matador to former skipper Don Zimmer’s enraged bull during a brawl with the Yankees. A midget coming out of the stands to cover third when the Indians used the “Williams Shift.”

This is the story of 100 years of Fenway Park, in chapter and verse, by the people who lived it.

A member of the Royal Rooters, a group of passionate Red Sox fans, sounded the drumbeat during a 1903 World Series game with the Pittsburgh Pirates at Huntington Avenue Grounds. The Rooters continued their antics for several years after the Sox moved to Fenway.

“Now for the opening of Boston’s magnificent new ballpark and a chance to see the Red Sox in action while leading the American League, a position gained while on the road.”

—

B

OSTON

G

LOBE

, A

PRIL

20, 1912

B

y the time Fenway Park debuted it was something of an anticlimax. The ballpark, which replaced the old Huntington Avenue Grounds, actually had been opened and used 11 days earlier when a handful of fans braved wintry weather to see the Red Sox shut out Harvard College in an exhibition. The game with the New York Highlanders (now Yankees) had been postponed by two days of rain. And most people were preoccupied with the

Titanic

, which had sunk on April 15 with several dozen New Englanders among those aboard. The day the new ballpark opened it was packed with 24,000 spectators, yet attendance for the season would total only 597,000.

Sporting News

predicted that the park would become more popular when people got accustomed to “journeying in the new direction.” In its first season Fenway hosted the World Series, and two years later it did so again—for the crosstown Boston Braves. The park’s colorful fandom featured saloonkeeper Michael McGreevy, society lady Isabella Stewart Gardner, and the raucous Royal Rooters, and they cheered the Sox to four world titles in seven seasons. But in Fenway’s early days, it was much more than the home base for the Red Sox; it hosted football, lacrosse, hurling, parades, memorials, and political gatherings. Former President Teddy Roosevelt attended an outing in 1914 at Fenway, 30 years before his cousin, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, gave the final campaign speech of his life there. The decade was capped by a rally for Irish independence attended by 50,000, by a world title captured in a season abbreviated by the Great War, and by a trade that would become the 86-year symbol of Red Sox futility.

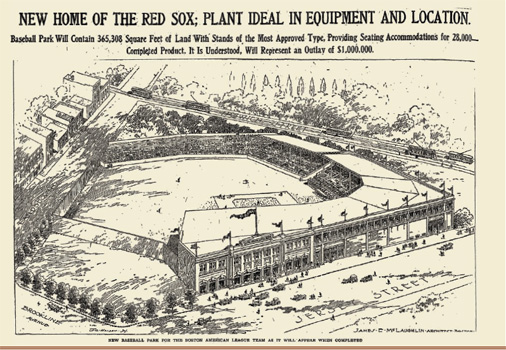

A rendering of the new ballpark from architect James E. McLaughlin was published in the

Boston Globe

, which estimated the cost of the park at $1 million.

F

rom the very beginning, the cherished and cursed home of the Boston Red Sox was the most misshapen and quirky collection of angles and corners in baseball. It was, John Updike wrote, “a compromise between Man’s Euclidean determinations and Nature’s beguiling irregularities.” Even the much-beloved name started as a simple tribute to geography. “It’s in the Fenway section, isn’t it?” the team’s owner said at the time.

The very genesis of Fenway Park was a matter of straightforward commerce. John I. Taylor was the owner of a ball club that played in a rented park. What he wanted was to own half of a club playing in a ballpark that he fully controlled, preferably in the embryonic neighborhood where his real estate company owned a large chunk of the reclaimed swampland that he and his partners hoped to develop into one of Boston’s desirable districts.

So he bought more than 365,000 square feet from his company, had architect James McLaughlin draw up plans and sold half of the Red Sox to former Washington Senators manager Jimmy McAleer for $150,000. Taylor then set about building what the

Boston Globe

promised would be a “magnificent baseball plant” between Lansdowne and Ipswich Streets. The new facility would be made of concrete and steel with a brick exterior that was a cross between a South End bowfront and a New England cotton mill and it would accommodate 28,000 spectators, twice as many as did the wooden Huntington Avenue Grounds in which the team had played since 1901.

Taylor, whose father Charles was publisher of the

Globe

, opted for the obvious and commercially convenient name of Fenway Park. The constraints of the site, cost, calendar, and concern for squinting batsmen led to Fenway’s endearing and infuriating dimensions.

Since Taylor didn’t want hitters blinded by the setting sun in an era when games began at 3:30 p.m., he had the diamond oriented with home plate looking out toward Lansdowne.