Fenway Park (58 page)

Authors: John Powers

WHO’S OUR DADDY?

When Pedro Martinez’s name came up in early 2010, nobody seemed to know what the former Red Sox pitching great was up to. He wasn’t at spring training. He wasn’t working on a deal to join a team at mid-season, as he had done with the Phillies the previous year. Some wondered whether he might be found under that mango tree in the Dominican Republic where he said he planned to spend his time after retirement.

But no, fittingly enough, Martinez made his first appearance of the year when he emerged from a tent in the left-field corner at Fenway to throw out the ceremonial first pitch on Opening Night vs. the Yankees. Wearing his familiar Red Sox No. 45 and blowing kisses and making hugging gestures to the fans, he strolled in from the outfield and back—at least fleetingly—into the Red Sox-Yankees rivalry that he was such a major part of. We remember his 17-strikeout effort vs. New York in 1999, when he allowed just one hit. We remember the duel in 2000 against the Yankees’ Roger Clemens when Trot Nixon homered to complete a 1-0 Sox win. We remember his throwdown of Don Zimmer in Game 3 of the ALCS in 2003. We remember, too, the eighth inning of Game 7 of the 2003 ALCS when Martinez, leading, 5-2, was left in too long by Grady Little in what became one of the historic meltdowns in playoff history. We remember Pedro after a victory in 2001 snarling, “I don’t believe in damn curses. Wake up the Bambino and have me face him. Maybe I’ll drill him in the ass.”

We remember him saying, after a loss late in the 2004 season, “I just have to tip my hat to the Yankees and call them my daddy.” That comment resulted in a crescendo of “Who’s your daddy?” chants from the New York faithful in his next outing there, in the 2004 ALCS. But the Red Sox busted the curse in that series, and Pedro ended his seven-year tenure with the Red Sox with a 117-37 record, a 2.52 ERA, two Cy Young Awards, and almost certain election to the Baseball Hall of Fame five years after he retires.

After the Sox split the first two in Baltimore the season came down to the 162

nd

game, and for seven innings everything was breaking Boston’s way, with the Sox leading 3-2 in the seventh and the Yankees drubbing the Rays 7-0. Then the skies opened in Baltimore and, during the 86-minute rain delay, the players sat in the clubhouse watching Tampa come back from the dead to even the score and send that game into extra innings.

Still, a Boston victory would mean at least a one-game playoff with the Rays and with two out in the ninth, nobody on base and closer Jonathan Papelbon on the mound, victory seemed assured. But two doubles and Robert Andino’s looping liner to left that Crawford couldn’t glove gave Baltimore a 4-3 triumph. By the time the Sox made it from the dugout to the clubhouse Evan Longoria had cranked a walkoff homer in the 12th to put the Rays into the divisional series.

“We can’t sugarcoat this,” Epstein conceded after Boston had missed the post-season in consecutive years for the first time since 2002. “This is awful. We did it to ourselves and we put ourselves in position for a crazy night like this to end our season.” That crazy night ended not only a season but also an era. Francona, who'd concluded that the front office wouldn't extend his contract, resigned two days later after eight years as skipper, frustrated that he couldn't get through to veterans who had a "sense of entitlement." Epstein soon followed him out the door to take on the challenge of rebuilding another ballclub that played in a storied park and that hadn't won a World Series for even longer—the Chicago Cubs.

Amid the upheaval and uncertainty, Sox owner John Henry made an impromptu and impassioned appearance on a local sports radio talk show to assure the public that stability and success would return. "We're going to be back as an organization," he vowed. "We're going to have a top-class manager and general manager and we're going to have a great team next year."

Whether or not the calendar included a Soxtober every year, management was continuing its mission to preserve Fenway for the next generation. Tiger Stadium, which had opened on the same day as Fenway in 1912, had gone under the wrecking ball in 2009. So had The House That Ruth Built, replaced by a $2 billion pinstriped pleasure dome across the street.

Boston, though, traditionally has been reluctant to toss its architectural treasures into the trash bin. A city that still has its original 18

th

-century State House and 19

th

-century City Hall has seen no reason to dismantle a 20

th

-century playground that still attracts more than three million ticket holders a year and has sold out every game since early in the 2003 season.

Fenway has undergone annual makeovers in recent years, with ownership spending $40 million in enhancements before the 2011 season—including the addition of three high-definition video screens. The total tab was 60 times more than the $650,000 that John I. Taylor had spent to build the ballpark a century earlier.

Over the past decade, John Henry and his colleagues have underwritten $285 million in improvements—from Monster seats atop the left-field wall to expanded concourses to a new playing surface—designed to carry the “lyric little bandbox” comfortably into the middle of the 21

st

century. Yet for all of the updating, America’s Most Beloved Ballpark remains essentially as it was in 1912. If Duffy Lewis were to return today, hunting for his misplaced glove, he wouldn’t need to ask directions to left field.

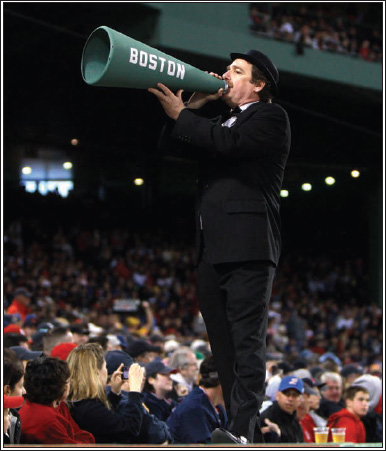

Game announcements and updates were made through a megaphone when the Red Sox played the Chicago Cubs on May 21, 2011—one feature of a series that marked the first meeting of the two teams at Fenway Park since the 1918 World Series. To commemorate the occasion, both teams wore throwback uniforms.

POP CULTURE

OK, so maybe the ballpark isn’t always the star. But it has certainly been a major player in movies and popular culture for much of its history.

Kevin Costner’s character saw old-time player Moonlight Graham’s name and hometown flash on the Fenway Park message board in the ultimate baseball movie

Field of Dreams

(1989), when he attended a game with Terrance Mann, played by James Earl Jones.

Drew Barrymore as Lindsey dropped from the center-field bleachers and sprinted toward boyfriend Jimmy Fallon in the box seats as hapless security personnel pursued her in

Fever Pitch

(2005), which required a last-minute revamp when the Red Sox confounded the scriptwriters and won it all in 2004.

Ben Affleck and his homeboys stole millions in receipts from a just-concluded Sox-Yankees series in

The Town

(2010), with final scenes filmed just inside Gate D of the park. In

Moneyball

(2011), Brad Pitt as Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane discusses a job offer from the Sox on location at Fenway. The park also had cameos in

A Civil Action

(1998),

Blown Away

(1994),

Little Big League

(1994),

Major League II

(1994), and numerous documentaries.

In July 2011, New Hampshire native Adam Sandler built a replica of the Green Monster on a Cape Cod Little League field to be used in filming a comedy due out in 2012 and tentatively titled, I Hate You, Dad. Several ballparks and Wiffle-ball fields throughout New England pay homage to Fenway, and another replica park, dubbed “Little Fenway,” hosts the Bucky Dent Baseball School (how dare he?) in Delray Beach, Florida.

On the small screen, in addition to being woven into the fabric of Cheers, Fenway occasionally played a part in Boston-bred producer David E. Kelley’s

Ally McBeal

and The Practice. It was also the setting for comedy sketches by Jimmy Fallon and Rachel Dratch, as Sully and Denise, on Saturday Night Live.

Novelist and Sox diehard Stephen King came up with the plotline for his novel

The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon

while at Fenway. A young girl lost for days in the Maine woods keeps up her hopes by tuning in Sox games on a Walkman.

Longtime Boston musician Jonathan Richman released a song in 2005, “As We Walk to Fenway Park in Boston Town,” that appeared in Fever Pitch. Other music associated with Fenway and its team includes the victory song “Dirty Water” by the Standells, Neil Diamond’s eighth-inning staple “Sweet Caroline,” “Tessie”—the Royal Rooters’ anthem that was resurrected by the Dropkick Murphys in 2004, “The Red Sox Are Winning” by Earth Opera, “Losing” by Pondering Judd, and the “Hot Stove Cool Music” series of benefit concerts spearheaded by Peter Gammons and Theo Epstein.