Fenway Park (55 page)

Authors: John Powers

The sight of Damon, clean-shaven and pinstripe-crisp, unleashed a cascade of boos when he made his return the following season to Fenway, where a “JUDAS DAMON” sign hung from a balcony. “People around here are born to hate the Yankees,” Damon shrugged. “That’s what they are booing, the uniform.”

Damon came back to torment his former supporters in August when New York tore the Sox to shreds with a five-game sweep that was even worse than the infamous Boston Massacre that sent the 1978 Sox into a tailspin. The carnage began with a Friday doubleheader that produced 12-4 and 14-11 defeats. The doubleheader consumed 8 hours and 40 minutes, with the nightcap establishing a mark as the longest nine-inning game ever at 4 hours and 45 minutes. It didn’t end until 1:22 a.m., after most of the faithful had departed.

Much of the damage was done by Damon, who was 6 for 12 with two homers, a triple, and seven RBI. But Saturday’s loss, a 13-5 pratfall in which Beckett walked nine batters and conceded nine earned runs, was even more unsightly. “Never happened before, to get beat up this bad,” concluded Ortiz after Boston had allowed a dozen or more runs in three consecutive games for the first time in franchise history. “Doesn’t matter where we were, we’re going in the wrong direction.”

After 8-5 and 2-1 losses completed the club’s first five-game sweep since 1954, the Sox had fallen six-and-a-half games behind New York. Boston ended the season 11 back in third place, their lowest finish in the division since 1997. It was, Epstein concluded, “an imperfect year” but it was followed by an extraordinary season that restored Boston to the top of the baseball heap.

MONKEY BUSINESS

It was a Monday night in October 2005, and Theo Epstein had just rejected a contract offer, seemingly ending his brilliant tenure as the 11

th

general manager in Red Sox history after just three years. In their basement offices, Epstein and members of his baseball operations staff saw camera crews gathering outside to capture him leaving Fenway Park. How could they get Epstein out of the building without facing the camera crush?

It happened to be Halloween, and someone had a gorilla costume handy. Epstein slipped into the suit and walked out of Gate D, past the cameras with a smile on his concealed face. Three months later, after Epstein had discussed working for the Dodgers and Sox CEO Larry Lucchino had talked with Jim Beat-tie about replacing Epstein, their feud was over. Theo was back in the fold, and his gorilla suit was being auctioned off at the annual benefit concert, Hot Stove, Cool Music—for $11,000.

After those negotiations became something of a spectacle in 2005 (Epstein called it “far too public”), he vowed that he would not reveal the end date of any future contract. Lucchino later said, “Walls have crumbled, perceptions of one another have changed, and appreciation of one another has grown.”

“I regret that it came to that and I wish we all could have handled it differently—me included,” said Epstein in 2007. “I’m not in this job to be recognizable or ‘famous’ on the local scene. I’m in this job because I want the Red Sox to have a chance to win the World Series every year and I like contributing at this level.”

With an unprecedented five playoff teams in his first six seasons as Sox GM, Epstein was not just another guy in a suit.

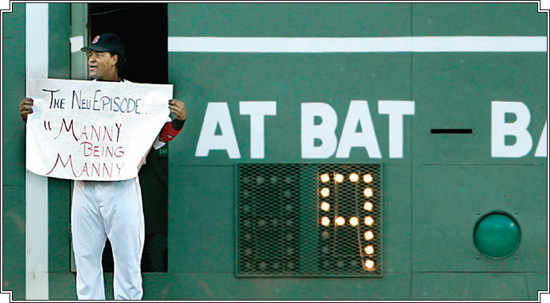

Before a game with Kansas City on August 2, 2005, Manny Ramirez showed off a sign that he had stashed inside the scoreboard of the Green Monster.

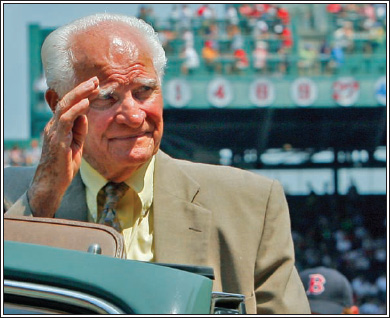

Bobby Doerr acknowledged the fans on August 2, 2007—“Bobby Doerr Day” at Fenway Park. Doerr’s No. 1 had previously been retired by the Red Sox in 1988. The number is displayed on the façade in right field behind Doerr.

Fenway denizens received an early hint that a remarkable season had arrived in 2007 when the Sox swept their first home encounter with New York in April, coming from at least two runs down to win all three games. After trailing by four in the eighth inning of the opener, Boston won, 7-6, when Coco Crisp knocked in two with a triple and Alex Cora singled him home with the winner. Then Ortiz knocked in four runs to spur his mates to a 7-5 triumph, and the Sox finished off the Yankees with four consecutive homers (from Ramirez, J. D. Drew, Lowell, and Varitek) off rookie left-hander Chase Wright in the finale.

“I haven’t been part of anything like that, not even in Little League,” marveled Lowell after the Sox had prevailed, 7-6, to sweep New York at home for the first time since 1990.

For the rest of the season, the Red Sox had the Yankees and everyone else in their rearview mirror, boosting their divisional lead to 11½ games on July 5 by sweeping Tampa Bay at home. The difference was a convenient convergence of inspired pitching and a couple of precocious rookies in second baseman Dustin Pedroia and center fielder Jacoby Ellsbury, the products of a beefed-up farm system.

The most intriguing newcomer, though, was Daisuke “Dice-K” Matsuzaka. The Sox lured the Japanese right-hander from the Seibu Lions with a $50 million contract after spending approximately that much for the privilege of chatting with him over sushi. Matsuzaka, known as “The Monster” back home, won 15 games to go along with 20 by Beckett and 17 by Wakefield. Jonathan Papelbon, a starter turned cold-hearted closer, chipped in 37 saves.

It was so dominant a staff that rookie Clay Buchholz, who pitched a no-hitter in September at Fenway in his second career start, didn’t make the postseason roster. For a pleasant change, reaching the playoffs wasn’t an arduous enterprise. Boston clinched a postseason berth with seven games to play and ended up with the best record in baseball (96-66) for the first time since 1946. More significant was the first divisional crown in a dozen years, which the Sox won in their clubhouse on the final weekend when the Orioles beat New York in extra innings after Matsuzaka had mastered the Twins.

The divisional series against the Angels went smoothly. First Beckett shut them out, 4-0, in the Fenway opener, and then Ramirez pushed the visitors to the brink with a three-run homer in Game 2, his first walk-off shot in a Boston uniform. “My train doesn’t stop,” declared Ramirez, echoing bash brother Ortiz after the 6-3 victory. The Angels had been rendered earthbound and the Sox finished them off two days later in Anaheim. “We didn’t come out of spring training to win the first round,” Lowell observed after Boston had scored seven runs in the eighth inning of a 9-1 smackdown. “We want to win the world championship.”

But getting to the Series proved more difficult than he and his comrades might have estimated in the wake of clobbering the Indians, 10-3, in the ALCS opener at Fenway. The tide turned dramatically the next night as Cleveland scored seven in the 11

th

inning, with old friend Trot Nixon sending home the winner in a 13-6 bust-up that lasted five hours and 14 minutes.

The Indians then won the next two games at The Jake by 4-2 and 7-3 counts, forcing Beckett to save the season with a 7-1 gem in Game 5. But once the Sox returned to Yawkey Way, they dispatched the Tribe with baffling ease. Drew’s first-inning grand slam fueled a 12-2 giggler to even the series, and the Sox scored six runs in the eighth inning of the seventh game on their way to an 11-2 win and trip to their second Fall Classic in four years.

The Rockies, who’d been up in the ozone while winning 21 of 22 games and powering past the Phillies and Diamondbacks to win their first National League pennant, were immediately brought to ground in the Series opener at Fenway, where they ran into hot Boston bats and icy pitching from Beckett. “You can’t make any mistakes,” sighed Colorado starter Jeff Francis after Pedroia had hit his second offering over the left-field wall to begin a 13-1 rout, a record margin for a Series opener.

CRIME OF THE CENTURY

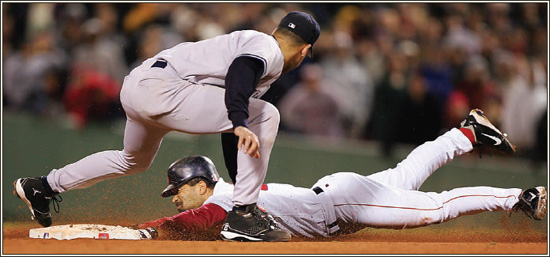

It was June 2007, and Dave Roberts was joking that the signature play of his career gets closer with each viewing.

“As I watch the footage from three years ago to two years ago to when I just saw it in the clubhouse, it gets closer and closer every single time,” said Roberts. “I hope five, 10, 20 years down the road that [umpire] Joe West doesn’t change his mind and call me out.”

On the basis of a three-second dash to second base in the ninth inning of Game 4 of the 2004 American League Championship Series, Roberts made himself into a Boston folk hero. Kevin Millar drew the walk, and Roberts ran for him. Bill Mueller got the single that drove Roberts in from second. Three people were involved in the manufacture of the run that saved the season and set the forces in motion for the greatest postseason comeback in baseball history, but somehow, Roberts’s star shines brightest in the telling.

“When I was with the Dodgers,” said Roberts, “Maury Wills once told me that there will come a point in my career when everyone in the ballpark will know that I have to steal a base, and I will steal that base. When I got out there, I knew that was what Maury Wills was talking about.”

Roberts was a 32-year-old outfielder acquired from the Dodgers about 10 minutes before the trading deadline (for minor leaguer Henri Stanley), on the same day Nomar Garciaparra was dealt to the Cubs. Roberts was strictly fine-print material.

“That whole team, from the moment I got there, had this undeniable belief that something special was going to happen,” said Roberts. When the time came, he was ready. “I was scared, excited,” he says. “I can’t tell you how many emotions went through me. He threw over once, and that was good because it helped settle me. He threw over again, and he almost picked me off. He threw over again, and now I was completely relaxed. I knew that after three throws they weren’t going to pitch out. I got a great jump. It was close, but, thank God, Joe West called me safe.”

“[Jorge] Posada made a great throw,” said Giants manager Bruce Bochy, recalling the play. “It was bang-bang. It just goes to show you what a thin line there is between winning and losing. Another few inches, and he’s out. And Boston’s done.”

Mueller’s single tied the game, and then David Ortiz delivered a game-winning, series-extending homer in the 12

th

inning.

Almost forgotten is the postscript: Game 5 at Fenway, eighth inning, 3-2, Yankees. Millar walks. Guess who pinch runs. Pitcher Tom Gordon is so obsessed with Roberts that he goes down 3-0 to Trot Nixon, who singles Roberts to third. Jason Varitek brings him home with the tying run on a sacrifice fly, and again, the Sox win in extra innings.

Roberts never again played for the Red Sox. Not in Game 6 or Game 7 of the ALCS, or in the World Series.

Roberts’s playing career was rather pedestrian. He was a .266 career hitter with 243 stolen bases in 10 seasons. He was a good teammate who could steal a base, slap a key hit, and play good defense in the outfield.

And in 2006, he was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame.