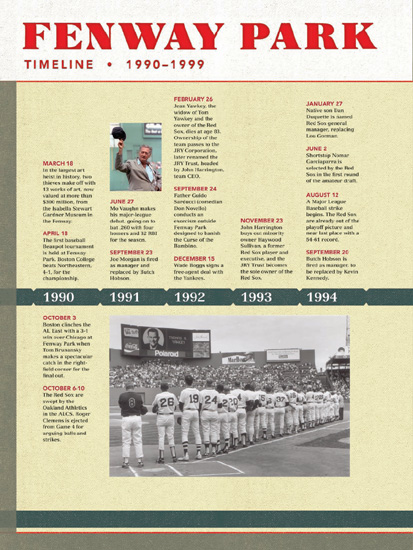

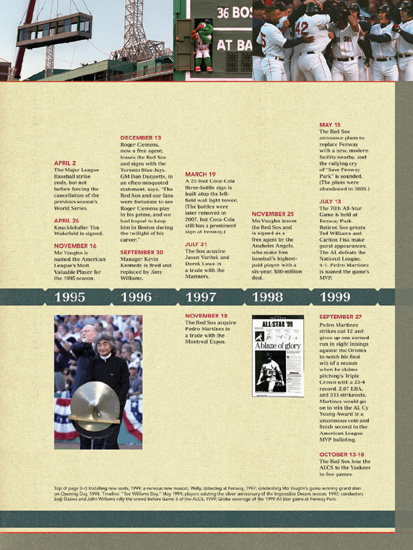

Fenway Park (50 page)

Authors: John Powers

Valentin’s two-run homer in the first was the opening shot in a barrage that put Boston up, 6-0, after three innings and put New York starter Clemens out of the game. “Where is Roger?” the fans chanted gleefully in the seventh inning, when the lead had soared to 13-0 and Martinez still was throttling the visitors. “In the shower.” It was the worst beating that the Yankees ever had taken in October and it made owner George Steinbrenner dyspeptic. “This can happen once,” he told his players in the clubhouse, “but it can’t happen again.”

New York turned the tables emphatically on Sunday night with a 9-2 victory that put Boston on the brink. Everything turned on a bad call by umpire Tim Tschida, who allowed an inning-ending double play in the eighth with Boston trailing, even though Yankees second baseman Chuck Knoblauch missed tagging José Offerman after fielding Valentin’s weak grounder. “No, I didn’t make the right call,” admitted Tschida. The furious crowd had agreed, littering the diamond with bottles in the ninth after Williams was ejected from the game for tossing his cap in the air.

As both teams were sent to their dugouts during an eight-minute delay, public address announcer Ed Brickley informed the spectators that the game would be forfeited unless order was restored. When play resumed, the Yankees ended things emphatically as pinch hitter Ricky Ledee hit a grand slam off Rod Beck. “It’s the first one to win four and it’s not over yet,” Williams declared in a statement while remaining secluded in his office.

But New York made sure of it a day later, clinching the series in five games with a 6-1 victory that produced its 36

th

pennant and set the stage for another Series ring. “We wanted to finish it here,” said Derek Jeter, who hit a two-run homer off Kent Mercker in the first inning. “We didn’t want to give them any life or confidence.”

While the Yankees sprayed each other with nonalcoholic champagne, the Sox, who’d had their best season in 13 years, were philosophical in defeat. “There’s nothing for us to hang our heads about,” Garciaparra proclaimed. “Disappointed? Of course. Any year we don’t win the World Series, I’m disappointed. But I’m not going to hang my head.”

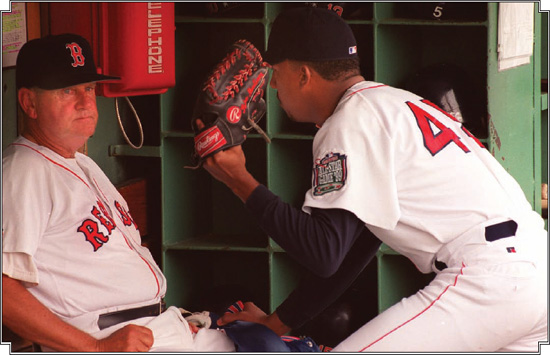

Pedro Martinez argued his case to manager Jimy Williams in the Red Sox dugout on August 14, 1999. Williams had refused to let the late-arriving Martinez start the game; instead, he went with Bryce Florie. Martinez pitched the last four innings and Boston came away with a 13-2 victory over Seattle.

A

lot more changed around Lansdowne Street and Yawkey Way in the 2000s than the millennium, as the Red Sox reached heights of success that had been seen only in the ballpark’s infancy, but not before yet another wrenching October setback. The Yawkey Trust put the team up for sale in 2001, and the new ownership group led by John Henry immediately promised to keep the Red Sox in Fenway Park for the foreseeable future. With that commitment (and the $700 million price tag) quickly came imaginative expansion of the seating that retained the charm and historic character of the park. In addition, after decades of relative quiet on all but 81 days a year, the doors were thrown open, and over the course of the emerging 2000s, Fenway became the scene of concerts, family and charity events, soccer games, citizenship ceremonies—even ice hockey games. Fenway retained its starring role as the Red Sox began a record sellout streak for major professional sports, but soon it was forced to share the spotlight when a bunch of scruffy underdogs took New England and Red Sox Nation on the wildest ride in postseason sports history. The self-proclaimed Idiots of 2004 won the final eight games of the postseason, many in heart-stopping fashion, to end 86 years of often excruciating frustration. The Sox went on to capture postseason berths in an unprecedented six out of seven seasons through the decade, while adding a second World Series sweep. In the process, they emphatically abandoned the label of front-runners who ultimately lost and took up the mantle of masters of come-from-behind victory. To wit, over three American League Championship Series, the Red Sox won nine consecutive games when facing elimination, going on to win two of the series and losing the third in Game 7. Curse foiled, again and again.

W

ith the new millennium and the club’s 100

th

season at hand, the Red Sox made two blockbuster announcements in 2000: there would be both a new ballpark and new ownership. Despite Fenway’s quirky charm and rich history, it was the oldest and smallest facility in the major leagues. “If we do nothing,” chief executive John Harrington declared in a

Globe

op-ed column on May 25, “we will be left behind.”

By the end of July, the front office, state, and city had agreed on a $665 million project, with nearly half of it to be publicly funded. The site, though, was undetermined, with management preferring the South Boston waterfront and Mayor Thomas Menino preferring the Fenway neighborhood. Meanwhile, the team was engaged in its annual battle—trying not to be left behind by the Yankees.

With Pedro Martinez and Nomar Garciaparra on track to retain their Cy Young and batting crowns, the Sox were in first place as late as June 22. But they faded during the summer and essentially were finished off on September 10 after the Yankees swept them at Fenway for the first time since 1991.

So the Sox finished second in the division for the third straight time and the Yankees went on to win their third consecutive World Series. And five days after the season ended, the For Sale sign went up on a franchise that had borne the Yawkey name since the Depression.

While Harrington wanted the next owner to be “a diehard Red Sox fan from New England,” management estimated that it would take at least a year to have a buyer step forward and be approved.

In the interim, the Sox were under pressure to close the gap between them and their pinstriped overlords in 2001. So the front office lured away Manny Ramirez from the Indians with an eight-year deal worth $160 million, the fattest contract in franchise annals and second only in all Major League Baseball to the $252 million deal that Alex Rodriguez signed with the Rangers that same day.

“I’m just tired of seeing New York always win,” said Ramirez, who grew up in Washington Heights, not far from Yankee Stadium, but who enthusiastically chugged a symbolic cup of chowder during his Fenway introduction. Ramirez, acquired for his prodigious ability to drive in runs, knocked in three against Tampa Bay in his new team’s home opener. That came just two days after right-hander Hideo Nomo had celebrated his Sox debut in Baltimore with a no-hitter, the first by a Boston hurler since 1965. So the fans began dreaming about October in April.

But as Martinez, Garciaparra, and Jason Varitek all struggled with injuries, things went sour in midsummer. Jimy Williams was replaced by Joe Kerrigan, the pitching coach, and the season came apart in late August with an 18-inning loss at Texas. The club lost 12 of its next 13 games, the death knell coming at Fenway with a weekend sweep by the Yankees. “We don’t have a monkey on our back,” Red Sox outfielder Trot Nixon muttered. “We’ve got a goddamned gorilla on our back.”

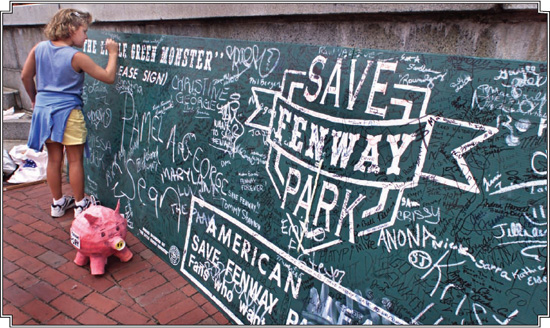

A “Save Fenway Park” mural outside the State House in Boston drew signatures from fans of all ages.