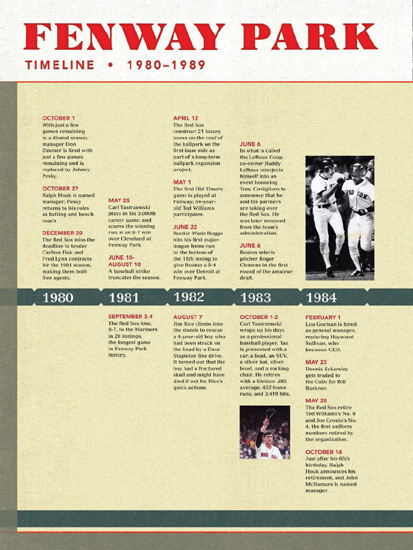

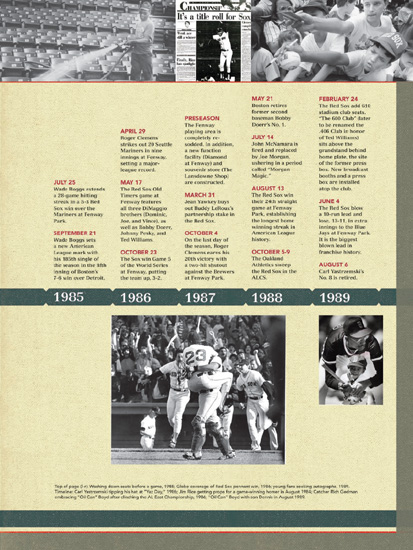

Fenway Park (46 page)

Authors: John Powers

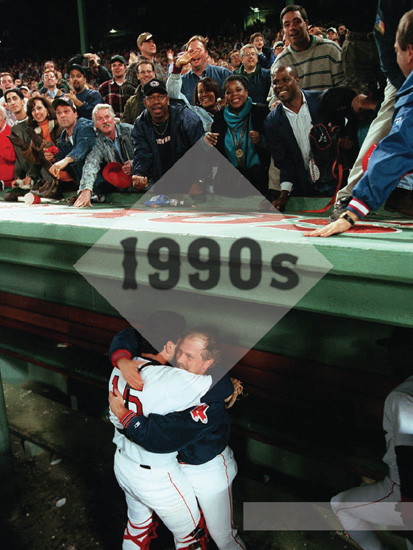

Catcher Mike Macfarlane (15) and outfielder Matt Stairs celebrated a win over Milwaukee that clinched the division title in 1995.

T

he decade started with turmoil, and the rumblings of discontent rarely abated throughout the Nineties. Roger Clemens was thrown out of Game 4 of the 1990 American League Championship Series, virtually assuring that the Oakland A’s would sweep the Sox for the second time in three years. After a late-season run the following year, the Red Sox lost 11 of their final 14 games, and put an end to the mini-era of Morgan Magic. The team rushed one of its gritty heroes of the late 1970s, Butch Hobson, into the manager’s seat—a position for which he seemed totally unprepared. Hobson guided the team to a 207-232 record over two-plus seasons and Boston’s first basement finish in 60 years. Hobson was released from duty in 1994—while baseball was out on a work stoppage that would cancel the World Series. Amazingly, attendance at Fenway improved after the strike. That 1995 season brought an unexpected AL East title, and in 1996, attendance improved by another 150,000. In 1997, though they flirted with last place before rallying to finish third, the Sox still averaged more than 27,000 fans per game. As Dan Shaughnessy put it in 1997, “This is Boston. This is Fenway. Fans come for the ballpark and the baseball. Strikes, losing teams, and off-field transgressions don’t matter much here.” By the time the petulant Clemens stomped out of town, bound for Toronto at the end of the 1997 season, he had long since worn out his welcome with many. He was replaced in fans’ hearts first by Mo Vaughn, then by Nomar Garciaparra, and finally by Pedro Martinez, who pitched the Sox to a playoff win over Cleveland. The 1990s and the millennium ended—fittingly, some would say—with an inspiring All-Star Game tribute to the Splendid Splinter, and a playoff defeat to the Yankees.

F

ollowing the 1989 shortfall, there was little reason to believe that Boston would be playing in October of 1990. But when Bill Buckner came back as a spring-training long shot, it seemed a cosmic sign of faith renewed. Buckner received a warm and redemptive Opening Day ovation from the forgiving, if not quite forgetting, Boston fans. Then he legged out an inside-the-park homer against the Angels on his first day in the lineup.

So it went for the Sox, who beat the Twins, 1-0, in a July game where they hit into two triple plays in five innings after conceding only two in the previous 25 years. Buoyed by magnificent pitching from Roger Clemens and Mike Boddicker, Boston built a lead of more than a half-dozen games by Labor Day. But after Clemens went down with a sore shoulder, the club dropped 10 of 12 and slipped behind the Blue Jays. The season came down to the final day at Fenway, with Boddicker on the mound; Boston needed a victory over the White Sox to avoid a playoff at Toronto, where Clemens already had been dispatched, just in case.

With the hosts ahead, 3-1, in the ninth and Chicago down to its last strike, champagne was at the ready. But Sammy Sosa singled and Red Sox closer Jeff Reardon plunked Scott Fletcher. Then up stepped future manager Ozzie Guillén to rip a line drive toward the right-field corner. Had it bounced past a diving Tom Brunansky, the game at least would have been tied. “No time to think about what I should do,” said Brunansky, who raced toward the noman’s-land by Pesky’s Pole. “I just had to do it.”

What resulted was one of the greatest catches in Fenway history, with Brunansky snaring the ball just before sliding into the wall. “Timmy, I’ve got the ball, I’ve got the ball,” he shouted to Tim McClelland, the first-base umpire, one of the few people in the park who had a clear view. “I saw the play,” McClelland said. “He never dropped the ball.”

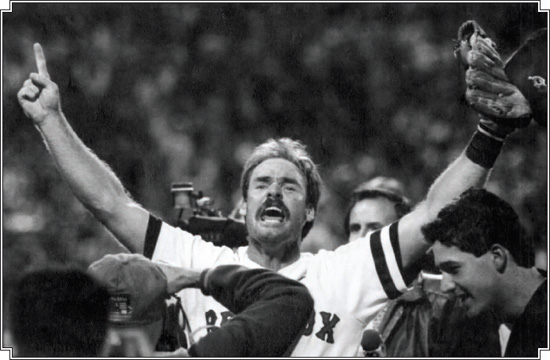

Thus did Boston claim the divisional title and earn a rematch with Oakland. “They called us misfits from the North Pole, castoffs,” said Wade Boggs. “We were etched in stone for seventh place. But this team has got heart and desire I’ve never seen before. A heart as big as the Pru.”

But up against A’s aces Dave Stewart and Bob Welch, the Boston bats were as useless as toothpicks, managing only two runs in the first two games at Fenway. “A beautiful game turned into a horrible evening, didn’t it?” mused manager Joe Morgan after the 9-1 opening loss, when Oakland bashed his bullpen for nine runs—seven in the ninth inning—after Clemens had blanked the visitors for the first six innings.

Wade Boggs rejoiced after the Red Sox clinched the 1990 East Division title with a victory over the Chicago White Sox.

The next evening was less horrid, but the 4-1 defeat sent the Sox to the Bay Area in a formidable pickle. “You don’t have to tell ’em too much now,” Morgan said. “They can read that easy enough.” Another 4-1 stumble in Game 3 put Boston on the verge of an early winter and after Clemens was ejected in the second inning of Game 4 for yapping at plate umpire Terry Cooney, his teammates went down by a 3-1 count, swept again and bitterly criticizing their manager.

“Those things don’t bother me,” Morgan said. “They don’t amount to a row of beans. I’ll tell you this—if a guy is going to manage in Boston, that guy better have some thick skin on his body. We’ve won two out of three years, so we must be doing something right.”

Boston would not play another playoff game for five seasons. The front office signed Clemens to a five-year contract worth more than $20 million. But before the 1991 season, there were multiple departures (Boddicker, Dwight Evans, Oil Can Boyd, Marty Barrett) and a few notable arrivals (Jack Clark, Danny Darwin, Matt Young). While Clark, acquired from the Padres, made a concussive entrance on Opening Day, clouting a grand slam in a 6-2 decision over Toronto, his new comrades were all but buried by midsummer, falling nine games behind after the Twins swept them by a 33-6 aggregate.

The Sox made a heroic late run, winning 12 of 14 in August and 17 of 21 in September, and found themselves only a half-game out of the lead on September 21 in the wake of hammering the Yankees, 12-1, at Fenway. “It’s not over yet,” cautioned Clark. “We’re still in second place.” That proved to be the summit for the Sox, who dropped 11 of their final 14 games to tumble out of contention. They came home to Yawkey Way for a somber farewell weekend. “Have a good autumn, a good winter and we’ll have a better year next year,” Morgan promised the fans before the Sunday finale against the Brewers.

Two days later, Morgan was gone, replaced by Butch Hobson, the Pawtucket skipper and former Sox third baseman the front office feared it would lose without a promotion. Morgan shrugged off his dismissal. “I think they just wanted a change, that’s all,” said the man who’d been the only manager other than Bill Carrigan to direct the Sox to the postseason twice in three years. “If they thought I wasn’t doing the job, they had every right to fire me.”

Hobson, who’d been in Winter Haven with the instructional team, was startled to learn he’d been upgraded. “I can’t believe this is happening to me,” he said following his Fenway introduction. “This is the greatest feeling in the world.”

LIGHTS OUT

Red Sox outfielder Ellis Burks was standing in the batter’s box, awaiting a 2-2 pitch from Chicago’s Jack McDowell, when Fenway Park did its best imitation of Boston Garden.

The Garden was where Bruins fans had seen games interrupted by blackouts, fog, and an occasional stray rodent on the ice, and where Celtics fans had seen games suspended by condensation on the court and interrupted by a pigeon on the parquet. But no such incidents interrupted the national pastime at 4 Yawkey Way. At least, not until the blackout of May 13, 1991.

As the Red Sox were waging a futile battle to erase a 2-0 deficit with two outs in the third, a power outage plunged Fenway Park and its crowd of 31,032 spectators into darkness for 59 minutes.

When the park went dark at 8:45 p.m., it was as though someone had begun a New Year’s Eve-style countdown. The blackout touched off a raucous ovation and created a rock concert atmosphere, complete with flickering lighters and a battery of flashbulbs.

The likely cause was a blown manhole cover that cut through a power line and knocked out electricity to several buildings in the area, including Fenway Park.

Radio station WRKO and cable TV channel NESN lost their broadcasts. Auxiliary power illuminated the seating areas, but the rest of the park remained shrouded in darkness.

Public address announcer Sherm Feller, in a partially lit press box, played to the fans as though he were doing a vaudeville routine in a dimly lit nightclub. Announcing to the crowd that the power outage was the result of a problem outside the park, Feller cracked, “Boston Edison’s working on it right now. If they send us a bill, we’ll pay it.”

The Fenway power outage was not unprecedented, though the previous one had gone relatively unnoticed by fans. “It was a weekday day game back in April 1981,” said Josh Spofford, Red Sox director of publicity. “We didn’t have any power the whole game. It was back when we were in the press box that was closer to the field, and Sherm led the crowd in the anthem a cappella and did the lineups with a bullhorn.”

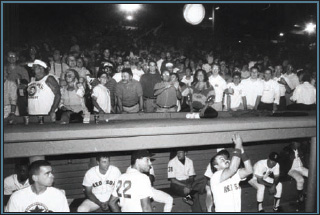

Players and spectators killed time batting beach balls during the Fenway blackout of May 13, 1991.