Fenway Park (47 page)

Authors: John Powers

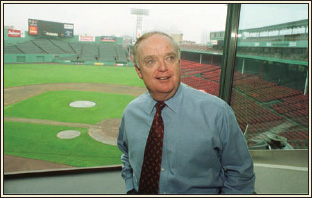

SOX CARETAKER

When Jean Yawkey died in 1992, John Harrington was entrusted to run the Red Sox. Harrington said that his goal was quite simple. “I just want to honor Jean’s generous legacy—and prove myself worthy of that trust.”

Harrington grew up in Boston and graduated from Boston College. While working as an accounting professor at BC, he was hired by Joe Cronin, president of the American League, to be the league’s controller in 1970. From there, he was hired by Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey to be the team’s treasurer. He eventually returned to the Red Sox in the mid-1980s and became an important adviser to Mrs. Yawkey.

After Mrs. Yawkey died, most observers expected that minority owner Haywood Sullivan, a former Red Sox player and executive, would buy out the Yawkey trust’s majority share of the team. Instead, Harrington, acting on behalf of the trust, bought out Sullivan’s general partnership stake in late 1993.

Sullivan talked about the relationship between Harrington and Mrs. Yawkey. “As the years passed, he became a kind of surrogate son. Certainly she depended on him more and more . . . and when he talked, you knew he was speaking for Jean.”

Harrington reveled in his role as Red Sox CEO, jesting that “every kid under 12 wants to be Nomar or Pedro, and every kid over 40 wants my job.” He acted as the chief negotiator for MLB owners during the 1994-95 strike, and he helped guide baseball’s divisional realignment to accommodate the wild-card playoff format in 1995. But in 2000—with the team in good financial and competitive shape, and state lawmakers apparently poised to approve funding for Harrington’s new ballpark project—he decided to sell the team on behalf of the trust. It was time to say good-bye.

“It was the right time for the team and the trust, and I knew I had to sell,” Harrington said.

But what had seemed a dream to the new manager, who brought back his old skipper Don Zimmer as third-base coach, turned into a summer nightmare in 1992 as the Sox went into a June swoon on the road, falling 9½ games out on the way to their first cellar finish since 1932, the year before Tom Yawkey bought the franchise. “This team isn’t as good as people think,” Morgan had declared on his way out the door.

With no .300 hitters and Clemens as their only dominant starter, the 1992 Red Sox lost 89 games—the most the franchise had dropped in a single season since 1966—and finished 23 games behind Toronto. It was a rude awakening for Hobson, who had never experienced a losing season as a player. “Maybe I was a little in awe of managing Wade Boggs or having Roger Clemens on my pitching staff,” he said. “That hasn’t sunk in with me.” It was an unsettling year for the franchise, which was thrown into transition when Tom Yawkey’s widow, Jean, died in February of complications from a stroke. John Harrington, Yawkey’s longtime confidant, stayed on as president of JRY Corp., which owned the Sox.

After another underwhelming campaign in 1993, when the Sox finished 15 games out in fifth place, Harrington shook up both the clubhouse and the front office. Gone after 11 years and more than 2,000 hits was Boggs, who departed for the Bronx. So was Ellis Burks, who changed red stockings for white.

During the autumn, Harrington bought out Haywood Sullivan’s interest in the franchise. He moved General Manager Lou Gorman to executive director for baseball operations and brought in Dan Duquette from the Expos as GM. The 35-year-old Duquette, a lifelong Boston fan from Dalton, Massachusetts who’d made the most of a shoestring budget in Montreal, arrived with a five-year mandate to make the club better by going both cheaper and younger, and to revamp a clubhouse that had 15 men who were 30 or older. “We’re going to renew the roster with new life,” Duquette vowed during spring training. By August, the Sox had suited up 46 players, half of them pitchers.

But the 1994 season was a lost cause by then. A 12-game home losing streak in June had mired Boston in third place, 10½ games behind. The breaking point came in a 10-4 home loss to New York during which Hobson had a meltdown and was ejected. He was later suspended five games for arguing with plate umpire Greg Kosc and bumping crew chief Larry Barnett after pitcher Sergio Valdez had been warned for throwing behind a Yankee batter. “There is a rage inside the guy [Hobson] that a lot of people don’t know about,” commented slugger Mo Vaughn. “If it goes, it goes. Behind this big job of being a

Red Sox manager is a man.”

On July 22, when his club returned to Boston 13 games behind after having been swept in Anaheim, Hobson passed out towels to his battered ballplayers. “I ain’t throwing mine in,” he told them. “Don’t throw yours in.”

Three weeks later, the towel was tossed in for baseball itself as the players went on strike for the first time since 1985. “See you at the Patriots games,” Vaughn told sportswriters after the finale at Baltimore had been washed out. The 54-61 record represented Boston’s third straight losing season, its worst stretch since 1966, and it marked the end for Hobson, who was summoned from his Alabama home to be dismissed in September.

“I believed in my heart that this day would never happen,” said Hobson, who later resurfaced as a scout and minor-league manager in Sarasota. “I’m not going to burn any bridges. When new faces come in, they want to bring in new faces. I know that.” The new face belonged to mustachioed Kevin Kennedy, who’d been Montreal’s minor league field coordinator and bench coach during Duquette’s time there and had just been fired by the Rangers. “This is the first and only place I wanted to be,” said Kennedy, who’d called Duquette as soon as Texas let him go.

An unprecedented winter of discontent followed the first canceled World Series, with the labor dispute remaining unsettled until March of 1995. It was unclear how the players would be received by fans when they took the diamond on April 26 for Opening Day.

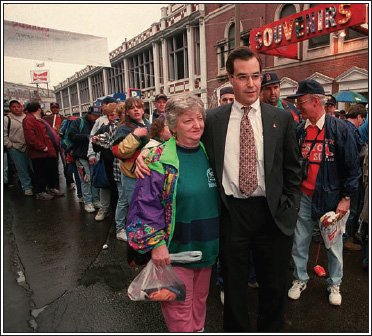

Knowing the importance of public relations, new Sox slugger Jose Canseco, who’d been acquired from the Rangers in December, was outside Fenway by 8 a.m., meeting and greeting ticket holders. “We can’t forget what really counts,” said his Sox teammate Mike Greenwell, who signed autographs for an hour after batting practice. “It’s the fans.”

Dan Duquette, a native of Dalton, Massachusetts, achieved his childhood dream of running the Red Sox in 1994. And though the Sox made back-to-back playoff appearances for the first time in more than 80 years on his watch, Duquette’s eight seasons as general manager were ultimately more tumultuous than triumphant. Duquette was considered one of baseball’s brightest young executives when then-CEO John Harrington hired him away from Montreal as the Sox GM. Though he showed some flashes of brilliance, he was fired in March 2002 when the team’s new ownership group led by John Henry decided they wanted their own man. “I’ve never had a bad day at Fenway Park,” Duquette said after his ouster.

A youngster had nowhere to go but down after making a lunge for a foul ball in a game at Fenway Park against the Chicago White Sox on April 29, 1995.

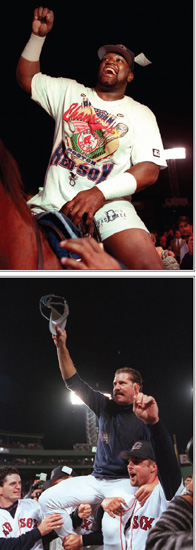

Mo Vaughn led cheers as he rode a Boston Police horse, and manager Kevin Kennedy got a ride from players Mike Macfarlane and Tim Wakefield, after the Red Sox clinched the AL East title on September 20, 1995.

And Sox fans seemed forgiving once their team had crushed Minnesota, 9-0.

The rebuilt and rededicated club took over first place on May 13 and stayed there for the rest of the season. Duquette, who’d reworked the roster (only three of the original 1994 starters were still in the lineup), kept tinkering, with 53 players (26 of them pitchers) suiting up by season’s end.

Boston ran away with the AL East, winning the divisional title for the first time since 1990 and clinching at home on September 20 with a 3-2 victory over Milwaukee. For their triumphal procession around the premises, the players mounted police horses—even Vaughn, their resident Clydesdale. “Everyone got on the horse and so I had to get on the horse,” Vaughn said, after John Harrington admitted that he was more worried about the horse than about his top slugger. “That’s the way this team is.”

The Sox were quickly unhorsed, however, in the playoffs by the Indians, who’d posted the league’s best regular-season record with 100 victories. The 5-4 loss in the 13-inning opener at Jacobs Field was doubly hard to take since the Sox led, 2-0, and then 4-3, in the 11

th

—and since Tony Pena, their former catcher, clouted the winning homer off Zane Smith with two out. After Orel Hershiser blanked the Sox, 4-0, in Game 2, the season came down to what knuckle-baller Tim Wakefield, who’d won 16 games after being picked up from Pittsburgh, could do with his notoriously unpredictable pitch.

The visitors were so confident they would finish off the Sox that they checked out of their hotel before the game. They then tagged Wakefield for seven runs in six innings, completing the sweep with an 8-2 triumph while extending Boston’s postseason losing streak to an unlucky 13. “Sometimes I wish I could throw a hundred miles an hour like Randy Johnson,” said Wakefield. Still, there was no disgrace in losing to a Cleveland club that went on to play in the World Series for the first time since 1954. “There are no excuses to be made for this series,” reasoned Kennedy. “We lost, they won, and we’ll be back.”

But it was the Yankees who were back in 1996, winning their first World Series since 1978. The Sox finished in the middle of the pack after pretty much dooming themselves by losing 19 of their first 25 games, and then falling 17 games behind in early July. Despite posting the best record in baseball over the final two months, Boston ended up in third place. Taking three of four from New York on the final weekend in Fenway provided a small bit of consolation. “It was emotional,” said Kennedy after the Sox had won the finale by a 6-5 count, and then packed their bags for the winter. “Maybe it wasn’t the intensity of winning a World Series game, but it was one we wanted.”