Fenway Park (42 page)

Authors: John Powers

While the dispute was being heard in January, the club traded Lynn and pitcher Steve Renko to the Angels for outfielder Joe Rudi and pitchers Frank Tanana and Jim Dorsey. When arbitrator Raymond Goetz ruled for Fisk, “Pudge” exchanged red socks for white and decamped for Chicago. Through a scheduling coincidence, Fisk played in his 10

th

Opening Day at Fenway (but his first as a visitor), where he cracked a three-run homer in the eighth that gave his new confrères a 3-2 decision.

“I honestly wasn’t concerned about how the fans were going to react to me,” said Fisk, whose line-drive home run quieted a crowd that hadn’t been sure all afternoon whether it should applaud or boo him. “I thought it would be mostly positive, which I feel it was. I knew there would be some hooters, but I thought the majority would be favorable because I don’t think I ever gave them any reason in all of the years I played here to feel any differently.”

Rich Gedman, up from the minors, was the part-time new man behind the plate with Glenn Hoffman at short and Miller in center, and the syncopated Sox were essentially out of contention by the end of April after dropping seven straight, including four games by a 28-8 aggregate during a sobering sweep by the Twins at Fenway. So a two-month players’ strike actually was a blessing, since Major League Baseball went to a split-season format when play resumed in mid-August, giving everyone a clean slate.

“Well, we’re only a game out,” Houk reckoned after Boston had been mugged, 7-1, by Chicago in Opening Day II at Fenway. Since the Sox had been four behind when the strike began, that constituted progress. By season’s end, though, the deficit was two-and-a-half games, which turned out to be the club’s closest finish to the top for five years.

While there was some satisfaction in playing a full slate in 1982, the Sox experienced a peculiar season that was as disappointing as it was encouraging. Despite winning 89 games (only five times in 30 years had they won more), they finished third, six games behind the Brewers. And though they were in first place at the end of June, the Sox subsequently dropped 10 of 13 games and never recovered. “We just weren’t quite good enough,” observed Clear.

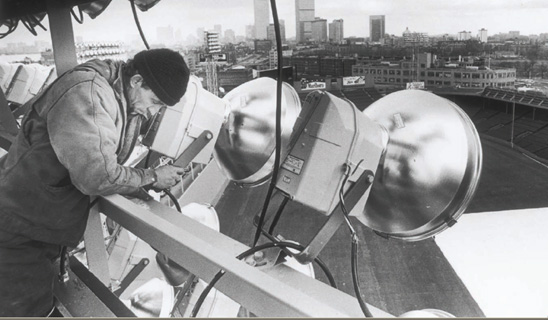

An electrician tinkered with some of the 95 lights on one of Fenway Park’s light towers in March 1983.

In April of ‘83, for the 10

th

straight year, Jane Alden put up bunting on the Red Sox dugout and along the right-field line.

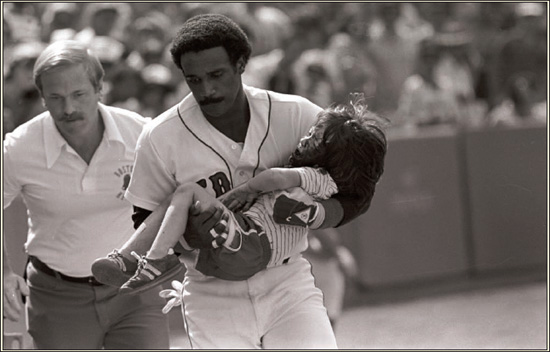

JIM RICE’S ONLY CAREER SAVE

One of the more emotional moments in Fenway history started as just another perfect summer Saturday at the ballpark.

On August 7, 1982, Tom Keane drove down to Fenway from his home in Greenland, New Hampshire, on the Granite State’s sliver of a seacoast, with his sons Jonathan, 4, and Matthew, 2. Keane had scored tickets for an afternoon game against the White Sox, and these weren’t just any seats. Through a friend, Keane had gotten tickets from Red Sox Executive Vice President Haywood Sullivan, and they were two rows from the field, just to the left of the Red Sox dugout.

“You were actually right there,” Keane told an ESPN reporter years later. “It was a seat that everybody would dream of when they had little kids and you wanted to get them close to the action. It was just ideal.”

The boys had cheered wildly when Sox second baseman Dave Stapleton—Jonathan’s favorite player—came to the plate in the fourth inning. But Stapleton swung late at a pitch and slashed a foul ball into the stands. The elder Keane didn’t see the ball, but he did hear a cracking sound. He thought the ball had hit the side of the dugout—until he turned and saw the blood coming down his son’s face. Jonathan had been hit by the foul ball and suffered a fractured skull.

Red Sox left fielder Jim Rice, who had been perched on the top step of the dugout, waiting his turn to hit, reacted instinctively. “Jim Rice was right there with his arms immediately,” Keane said, “I mean immediately.”

Rice was described by the media of the day as standoffish, or even sullen. His reserved manner was fortified for a time by an impression that, as an African-American ballplayer, he wasn’t as warmly received by Boston fans as a white superstar would have been. And as an eight-time All-Star and the American League’s MVP in 1978, Rice certainly qualified as a superstar. But none of those perceptions mattered one bit on that day, when Rice’s quick reaction may have saved Jonathan Keane’s life.

Rice, a father of two young children, later said he was thinking of one thing, and one thing only. “My child,” he said. “Just someone, myself, just taking care of my child, picking my child up and taking him to the clubhouse.”

“I was kind of chasing Jim Rice; he was carrying Jonathan,” said Keane. “There was an ambulance waiting. When we got to the hospital, they were set up for neurosurgery.”

Doctors at Children’s Hospital, just a mile away, relieved the pressure on Jonathan’s brain and gave him medicine to guard against seizures. He was hospitalized for five days.

Eight months later, Jonathan was reunited with Rice. On April 5, he threw out the first pitch at Fenway to open the 1983 season.

“Obviously, as we sit here today, what he did saved [Jonathan’s] life,” Keane said. “I mean you had a young child, his left skull is fractured open, it is bleeding profusely. The worst could have happened.”

Said Rice, years later, “Playing baseball was more of a talent than a gift. The reaction to save somebody’s life, that’s entirely different.”

Boston was nowhere near good enough in 1983, when the club finished 20 games out in sixth place with its worst record (78-84) since 1966. Everything went sour in early June, when minority owner Buddy LeRoux announced a takeover (the so-called “Coup LeRoux”) that provoked an immediate riposte from Sullivan. The dueling press conferences, observed

Globe

beat man Peter Gammons, resembled “the staging of a Mel Brooks parody of post-Mao China.”

The front-office turmoil sent an aftershock through the clubhouse as the Sox promptly were swept at home by the Tigers and went on to lose seven in a row, tumbling from first place to fifth in less than a week. “I can’t believe what I saw,” said a nonplussed Houk after a comedy of errors resulted in a 10-6 loss to the Orioles. “I’ve never seen so many things happen like that in my life.”

The rest of the season was forgettable, except for the finale, when Yastrzemski made a farewell tour of the park where he’d performed with both dignity and distinction for 23 years. “They just kept saying, ‘We love you, Yaz,’ over and over,” he said after the fans had saluted him. “I’ll never forget it.”

That was the end of an era that began with the departure of Ted Williams and ended with the blossoming of Wade Boggs, who won the batting title in only his second year with the club by hitting .361 in 1983. Yastrzemski wasn’t the only familiar face missing from the starting lineup when the club convened for 1984. Gedman had taken over for Gary Allenson behind the plate; Bill Buckner (obtained from the Cubs for Dennis Eckersley) was at first; Marty Barrett stood in for the hobbled Jerry Remy at second; Jackie Gutierrez replaced Hoffman at short; and Mike Easler (obtained from Pittsburgh for John Tudor) was the designated hitter.

It was a dramatic changeover and after losing 10 of their first 14 outings, the Sox were 10 games off the pace by the end of April. Yet with a young rotation—that included Bruce Hurst, Dennis Boyd, Bob Ojeda, and Al Nipper—gradually finding its way, the club’s stock clearly was on the rise, most notably with the arrival of right-hander Roger Clemens, the top draft pick from the previous year who debuted on May 15 and quickly established himself as an overpowering force.

His dominance of Kansas City in an August date at Fenway was a high-octane preview of future performances, with Clemens striking out 15 batters with no walks and only 31 balls to 33 batters. “The sound you heard was me: Owww!” testified catcher Jeff Newman. “He done hurt my hand.” The Royals, who managed one run across nine innings, were duly impressed. “That was the best stuff we’ve seen all season and we’re not going to see better,” declared Mike Ferraro, a Royals coach. “He has the best stuff in the American League, hands down.”

IN THE LAP OF LUXURY

The 1980s gave us the concept of corporations slapping their names on stadiums for a price, and the debut of the luxury box, including at Fenway Park.

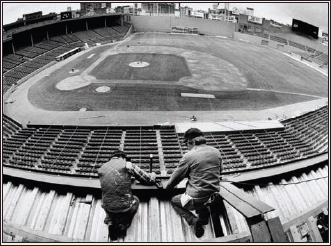

In 1980, the Red Sox began to realize they could no longer survive with the park as it stood. With only about 34,000 seats and an escalating payroll that could not be met by ticket sales alone, Fenway Park was in danger of crumbling under the financial stresses of the day.

Before 1970, players made an average of $20,000 per year; by the early 1980s, they were making more than $100,000 on average. There once was a time when owner Tom Yawkey didn’t worry about finding new ways to generate revenue, but Yawkey was gone. He had died of leukemia in 1976.

The Red Sox constructed 21 luxury boxes on the roof of the ballpark along the first-base side that debuted during the 1982 season. They later added boxes on the third-base side and behind home plate that brought their total to more than 40 luxury boxes (or suites), with an average of 14 seats per box, at a rental price of $50,000 to $70,000 per season.

From the day he took over the Sox business operations, Red Sox co-owner Buddy LeRoux set out to raise revenues. Along with constructing the luxury boxes, he increased ticket prices dramatically and eliminated Yawkey’s policy of saving 6,500 bleacher tickets for sale on the day of a game. The interest on money deposited for advance ticket sales was believed to have brought the Red Sox as much as $2 million a year at that time. LeRoux’s plan to add a second tier of seats, some 6,000 of them, atop the luxury boxes was never implemented.

LeRoux’s approach ran counter to the Yawkey philosophy that no one should invest in sports to get rich.

Eventually, the ownership battles between LeRoux and his limited partners on one side and Sullivan and Jean Yawkey, Tom’s widow, on the other, culminated in LeRoux being bought out of his ownership stake by Mrs. Yawkey in 1987.