Fenway Park (37 page)

Authors: John Powers

Fans scaled a billboard to peer into Fenway Park in 1971.

Boston needed divine intervention after losing, 4-1, in the series opener against the Tigers. Beating Tigers ace Mickey Lolich, who posted 15 strikeouts, would have been challenging enough. But the Sox literally tripped over themselves as Aparicio, who would have scored the lead run, stumbled rounding third on Yastrzemski’s third-inning double in a painful reprise of his Opening Day pratfall at Tiger Stadium that cost the club a victory. “I stepped on top of the bag instead of the corner and then I hit a soft spot on the grass,” said Aparicio, who gashed his right knee with his left foot when he went down. “How dumb can I be, spiking myself?” he groaned.

Yet it was Yastrzemski who made the killer mistake, steaming toward third without noticing that his teammate had gone down and that Eddie Popowski had called Aparicio back to the bag. “There was no way then to hold Yaz to second,” the third-base coach said after Yastrzemski had been tagged out. When the Tigers finished them off the next day, some Sox players wept in the clubhouse. “You came a long way and have nothing to be ashamed of,” Kasko told them.

Had Boston not given up so much ground in the early going, the season might not have come down to an untimely slip. “I told Haywood Sullivan I didn’t want to come to Boston next June and find the team eight or nine games back,” Yawkey said. “We’ve tried that too often.”

The 1973 season started sublimely, as the Sox swept the Yankees at Fenway for the first time in an opening series since 1933. “Ah, Tiant et Fisk et Yaz, quisque cum clangore epico ballatorum ex Iliade,”

Globe

columnist George Frazier exulted in Latin after the Tibialibus Rubris had clobbered Eboracum Novum by a count of XV-V.

The introduction of the designated hitter provided added oomph to a Sox lineup that needed more production, with Orlando Cepeda clouting the winning homer in the ninth inning of the third game. “I see about 15 guys at home plate,” marveled Cepeda, who’d been signed as a free agent. “It looks like the World Series kind of homer.”

But the early euphoria vanished when Boston dropped four to Detroit at home. By the beginning of May, the club was stuck in sixth place and didn’t get above .500 until late June. Though four victories in New York in early July moved the Sox from fifth place to third, even an eight-game winning streak in mid-August made up no ground on the runaway Orioles, and Boston ended up eight games in arrears.

That was enough to get rid of Kasko, who was dismissed before the final day of the season and never managed again. “We are the ones who let him down,” said pitcher John Curtis. “I can’t look at this season and say we gave it our best shot.”

RAY, LITTLE STEVIE AND ALL THAT JAZZ

On July 27 and 28 of 1973, the famed Newport Jazz Festival came to Boston. Not only that, it came to Fenway Park for two shows, with a stage set up near second base and a portion of the ballpark’s seats cordoned off. Attendance was reported as 14,000 for the first night, and 21,500 for the second night of the festival, which is traditionally held in Newport’s Fort Adams State Park. Concertgoers were both fascinated and disoriented. The Globe’s Ernie Santosuosso admitted that “even I kept casting instinctive glances toward the board for out-of-town scores.”

Globe

reporter William Buchanan covered the first night’s five-hour-plus performances, and he was obviously unaccustomed to the ballpark comforts. “All due respect to you, Mr. Yawkey,” he wrote, “those Fenway seats could test the mightiest of Spartans after an hour or two.”

The featured artists on Friday were Freddie Hubbard, Billy Paul, War, Herbie Mann, the Staples Singers, and Ray Charles. Not a bad lineup for a ballpark concert, although some fans were irate when it turned out that they had bought counterfeit tickets from scalpers, while, Buchanan noted, “There is still an obvious problem with pickpockets [outside the ballpark]. Youthful teams of two or three would jostle an unsuspecting fan and woosh, the wallet is gone.” Inside the park, he noted, “Boston police were polite but firm, and that made for a generally relaxed feeling.”

Among the highlights were: Paul’s “Me and Mrs. Jones,” which had won him a Grammy Award earlier in the year; War’s 50-minute set, and the “musical and spiritual togetherness” it inspired; and Charles’s “What’d I Say,” though Buchanan noted that the lineup of backup singers to Charles, known as the Raelettes, was “a bit weak.”

The second night’s lineup included B. B. King (in a silver-gray suit and accompanied by a nine-piece band), Stevie Wonder and Donnie Hathaway, plus Charles Mingus and Roland Kirk. During Hathaway’s set, according to the

Globe

’s Ray Murphy, “hundreds streamed onto the Fenway infield, but they finally returned to their seats after the earnest pleading of Hathaway himself.”

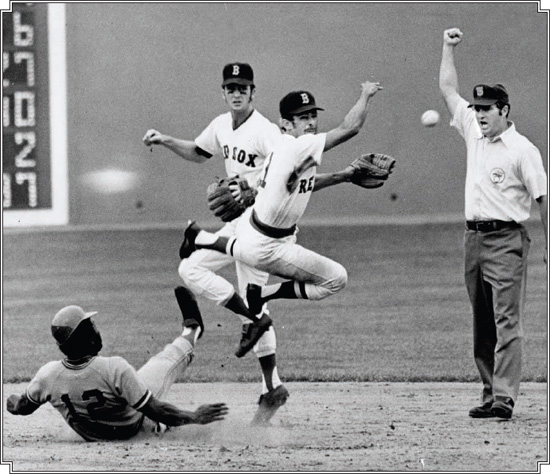

Luis Aparicio, a Hall of Fame shortstop who played three seasons with the Red Sox, turned this double play on September 27, 1972.

With the new manager (and former Pawtucket skipper), Darrell Johnson, preaching defense and equality (“All of us have the same rules, nothing special for anyone”), the Sox remained near the top of the standings in 1974, moving into first place on May 22 after bashing the Yankees, 14-6 and 6-3, at Fenway and staying there for most of the summer even without Fisk, who tore knee ligaments in a home-plate crash in Cleveland at the end of June. “We’re no longer a team that waits for something to happen,” declared Yastrzemski. “Over 162 games, this is going to be a better team.”

But as the bats lost their pop, Boston began losing ground and fell out of first place with a home loss to New York in September. When the club was starved, 1-0, in both ends of the Labor Day doubleheader in Baltimore with aces Luis Tiant and Bill Lee on the mound, the slippage began in earnest. The Sox soon fell out of first after losing to the Yankees and ended up dropping 16 of 21 games. When the soaring Orioles took two of three in their next series at Fenway, bashing Sox hurler Reggie Cleveland, 7-2, in the finale, a young man rose behind the home dugout in the ninth inning, put a bugle to his lips, and played “Taps.” “We’re going to have to win almost every game now,” acknowledged Johnson.

When the end came, with barely 5,000 witnesses rattling around the Fenway stands for a date with the Indians, the Sox were seven games out, finishing third behind Baltimore and New York. “Well, to say that I’m not disappointed would make me a damn liar,” said Yawkey as he prepared to head to his South Carolina plantation for the winter.

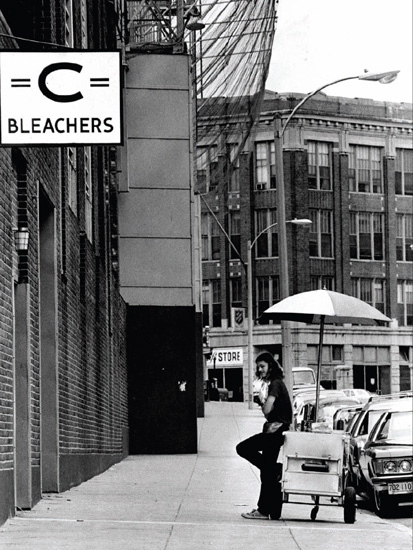

A hot dog vendor on Lansdowne Street awaiting the game-day bleacher crowd in August 1975.

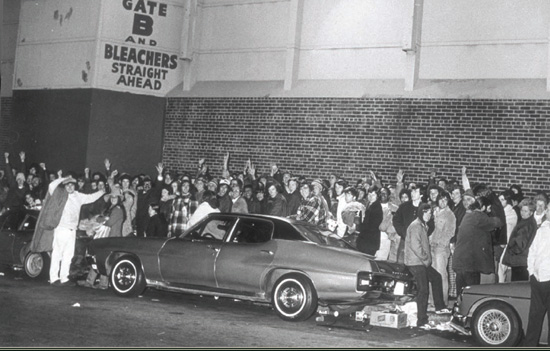

The prospect of World Series tickets prompted crowds to camp out all night in October 1975.

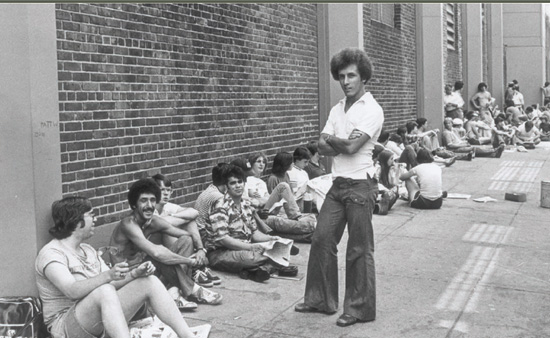

Fans awaited the sale of bleacher seats for Red Sox-Yankees games in June of 1978.

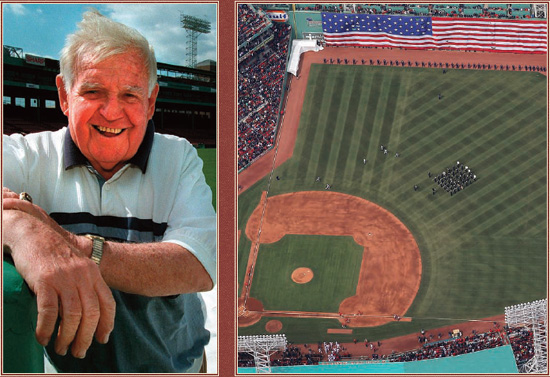

JOE MOONEY: SPLENDOR IN THE GRASS

From 1971 to 2000, Joe Mooney was the keeper of the greensward, the man behind the meticulously manicured Kentucky bluegrass at Fenway Park that always leaves first-time visitors—not to mention some frequent attendees—agape. As the head groundskeeper for the Red Sox for some 30 years, he liked to point out that his career in baseball stretched from Schilling to Schilling—Chuck to Curt.

“I worked for the minor-league team in Minneapolis in the late 1950s and used to pitch batting practice to [former Red Sox] Chuck Schilling and Carl Yastrzemski,” said Mooney.

A native of Dunmore, Pennsylvania, Mooney worked at Red Sox minor-league parks in Louisville, San Francisco, and Minnesota before he broke ranks and went to work in Washington, D.C. There he kept up D.C. Stadium (later renamed RFK Stadium) for professional teams that featured a pair of legendary coaches. Former Red Sox legend Ted Williams managed the Washington Senators at the time, and Vince Lombardi then coached the Washington Redskins.

“Imagine working for those two guys,” said Mooney. “It didn’t come any better than that.”

Mooney also credits Williams for helping him land his job with the Red Sox. He had spent much of his 10-year stint in D.C. improving a poorly designed field, and Fenway was in need of an overhaul as well.

“They had tried out a different grass—rye, I think—that couldn’t take the gaff, and they had a lot of fungus,” he recalled. Mooney solved the Fenway woes and transformed the park into a dazzling beauty. Ask Yaz, who patrolled left field and first base while Mooney groomed the grounds: “Fenway is the best there is, at least since Joe Mooney started working on it.”

Mooney was known to throw interlopers off his field, regardless of their title or temperament. His customary explanation was this: “You walk on grass too much, it gets beat up.”

In 2001, Mooney ceded control of the field to Dave Mellor while he continued to supervise maintenance of much of the rest of the park. In the winter of 2004, the Fenway drainage system was renovated, leaving Mooney shaking his head.

“When I came here, we had three drainage pipes; now there will be 50,” he said. Even for groundskeepers, “it’s a different game.”