Fenway Park (33 page)

Authors: John Powers

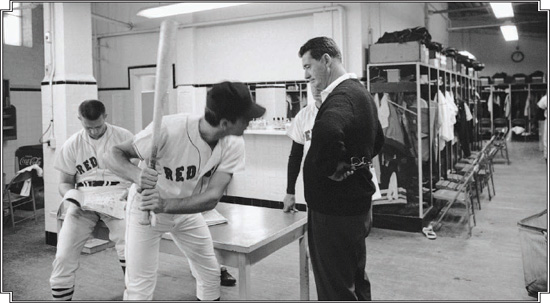

Tony Conigliaro worked on his batting stance in the Fenway Park dressing room under the watchful eye of then-Red Sox vice president Ted Williams on July 21, 1966.

Even that feat wasn’t enough to keep Yawkey from dumping Higgins as his general manager in the middle of the game—Higgins’s second sacking by the Sox in six years. The former skipper, who’d been the primary target of fans’ displeasure, had advised the owner to fire him. “You’d be better off with somebody else,” Higgins said. “I’m not popular in this town.”

Yawkey first said the change would be made during World Series time. But he lowered the boom in the fifth inning (“I’d like to make that change now”), giving Morehead 45 minutes to savor his no-hitter before announcing the decision to the public. Replacing Higgins was Dick O’Connell, who quickly shook things up by moving spring training from Arizona to Florida and promoting farmhands like George Scott, Joe Foy, Reggie Smith, and Mike Andrews.

But the club still finished ninth in 1966, dropping its first five games and 20 of 27. By mid-May, the Sox were in last place. “You’re always optimistic in spring training,” Yastrzemski wrote in his memoir,

Yaz

, “but that optimism’s gone after the first two months of the season when you’re 25 games out of first place and looking at 2,000 people in the stands in springtime.”

It was no consolation that Boston finished the season ahead of New York. The franchise was going sideways and attendance still was well under a million. So O’Connell brought in Dick Williams, who’d been the Triple A manager in Toronto and who insisted on two things—a one-year contract and absolute autonomy in the dugout. “I decided if I’m going to go down, I’m going down my way,” said Williams, who’d been a reserve infielder on the Sox soporific 1963 and 1964 teams where “nobody really cared about winning.”

Given the dismal denouement of the previous campaign, expectations for the coming season were modest by the players and less-than-modest by oddsmakers, who listed the Red Sox as 100-1 long shots. “If our pitching holds up, we’ll finish fifth,” reckoned Yastrzemski, the club’s perennial cockeyed optimist. “No kidding. I think we can make it to the first division.”

That’s precisely where the Sox found themselves in mid-July after a 10-0 home loss to the Orioles. Though none of them predicted what was about to occur—a 10-game winning streak that lifted Boston to second place, a half-game behind Chicago, and bestirred a fandom that long ago had been lulled into somnolence.

“Our mouths were open,” shortstop Rico Petrocelli said after 15,000 Sox fans turned up at Logan Airport to salute the players upon their return from a four-game sweep of the Indians in Cleveland. “We were shocked. That’s when we started believing.”

The summer of 1967 was a revival, a daily salvation show for both the Sox and their supporters, whose souls had been deadened by decades of disappointment. It was the wildest ride in memory as the club went from first place to ninth to first to eighth, all before Memorial Day. Attendance was on its way to doubling to more than 1.7 million—the franchise’s highest ever.

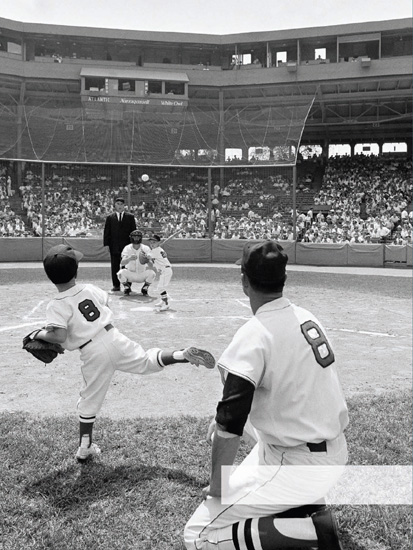

In the annual Father-Son Game, on July 24, 1966, Mike Yastrzemski, 4, threw a pitch as dad Carl offered support. Vin Martelli, 5, godson of Sox outfielder Tony Conigliaro, was the batter, while George Thomas of the Red Sox caught and umpire Hank Soar called the balls and strikes.

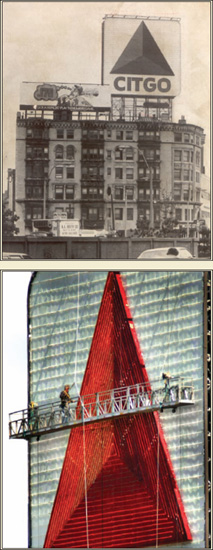

BALLPARK BACKDROP ENDURES

For nearly five decades, Red Sox fans have watched home-run blasts over the Green Monster soar against the backdrop of a Boston landmark. When the Citgo sign in Kenmore Square was first illuminated in 1965, it replaced a 1940 neon sign that displayed the shamrock logo of Cities Services, the predecessor to Citgo.

The pulsating, computer-controlled design of the 60-by-60-foot sign was an immediate hit in the psychedelic age, and an avant-garde filmmaker made a critically acclaimed three-and-a-half-minute film in 1967 called

Go, Go Citgo

, in which he set the sign’s display to music by the Monkees and Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar.

The sign became so renowned that even opposing managers knew it well. In 1978, with Sox slugger Jim Rice on a particularly torrid stretch, Royals manager Whitey Herzog deployed a four-out-fielder shift. “What I’d really like to do is put two guys on top of the Citgo sign and two in the net,” Herzog quipped. Rice beat the shift by hitting one over the left-field wall and the netting for a home run.

Bostonians have taken their skyline pretty seriously ever since Robert Newman placed two lights in the tower of the Old North Church in 1775 as a beacon to Paul Revere. This may explain why plans to tear down the Citgo sign caused an uproar in 1982.

In September 1979, at the urging of state officials, Citgo had turned off the sign to set an energy-conservation example, even though it cost only $60 a week to light. By November 1982, Citgo was preparing to tear it down.

The public was outraged. The sign’s supporters even urged the Boston Landmarks Commission to make it an official landmark. A man who testified before the commission said, in complete seriousness, “Paris has the Eiffel Tower, London has Big Ben, and Boston has its Citgo sign.” On November 16, the Landmarks Commission issued a cease and desist order.

“We had no idea it would receive such a response. Now we know how much people in Boston love that sign,” Citgo spokesman Kent Young later said. By August 1983, the sign was again aglow.

In 2005, more than 1.7 miles of LED lights replaced the existing 5,878 glass tubes of neon, which saved thousands of dollars in energy costs. But when those LED lights went out of production in 2010, crews replaced the sign’s 218,000 lights with brighter, more weather-resistant versions.

Citgo is a division of Venezuela’s government-owned oil company, and in a 2005 relighting ceremony, Mayor Thomas M. Menino of Boston flipped the ceremonial switch with Juan Barreto, then mayor of Caracas, and former Red Sox shortstop Luis Aparicio, the only Venezuelan in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The sign continues to glow, part symbol of roadside culture, part Boston icon, and some fans still call out “See it go!” (C-IT-GO) when a Red Sox player blasts a home run in its general direction.

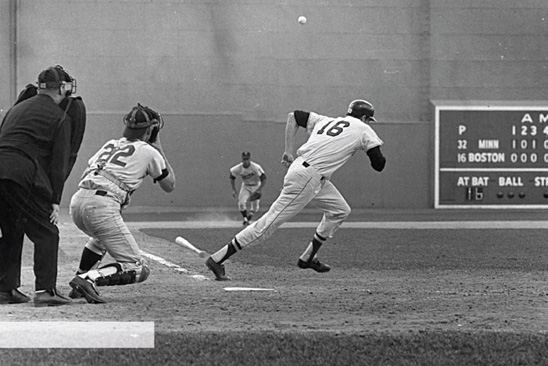

Jim Lonborg laid down the bunt for a base hit that triggered the winning Red Sox rally in the final game of the 1967 “Impossible Dream” season. The Red Sox trailed the Minnesota Twins, 2-0, in the sixth when Lonborg set the table for a five-run inning and an eventual Boston victory. The Red Sox edged the Twins and Tigers by one game for their first pennant in 21 years.

WHEN RED SOX NATION WAS BORN

They listened on transistor radios in the clubhouse for the crackling report from Detroit’s Tiger Stadium. It was October 1, 1967, and the Red Sox had held up their share of the deal by defeating the Twins earlier in the day, clinching no worse than a tie for the AL pennant. Fans had stormed the field to hoist pitcher Jim Lonborg onto their shoulders, and players bathed in adulation from success-starved Bostonians who couldn’t quite believe that their longtime American League doormats could be going to the World Series.

The Red Sox had started that 1967 season with a victory on Opening Day—before a mere 8,234 fans. It turned out to be the Summer of Love nationally, but in New England, it was the summer when the lovable losers of Fenway became a team that mattered, a team that played meaningful games in late summer and fall.

Globe

columnist Dan Shaughnessy, who was 13 years old that year and had never seen a decent Sox team, years later wrote: “The Red Sox of the new century are still beholden to the Impossible Dream crew.”

Red Sox teams of that era didn’t fall out of the pennant race in the final weeks—no, they were usually out of any consideration by the Fourth of July. The Boston clubhouse was known as a “country club” where star players had only to run to the owner, the benevolent Tom Yawkey, if they thought a manager wasn’t treating them fairly. They had coasted to eight consecutive losing seasons, finishing eighth, seventh, eighth, ninth, and ninth in a 10-team league the previous five seasons.

Now, as the “Age of Aquarius” dawned, a rookie manager named Dick Williams was in charge, and it seemed he had some backing from above. The Sox, a collection of retread players and youngsters led by two stars who were having the seasons of their lives, had reawakened a generation of Red Sox fans. By July, they were in first place, a totally unexpected perch. They hung on with improbable determination and entered the season’s final weekend with two home games against the Minnesota Twins, who led them by one game in the standings. Win two, and the Sox could do no worse than tie for the pennant with the Detroit Tigers.

Boston fans were wild for “Gentleman Jim” Lonborg’s pitching, and yet he triggered a game-changing rally with—of all things—a bunt single, as Boston defeated the Twins on the season’s final day. It was Lonborg’s 22

nd

victory of the season, and it would help earn him the Cy Young Award, the first such honor for a Red Sox pitcher.

The tale of Don Quixote was all the rage on Broadway that season, and, thus, the Red Sox rebirth was tagged—forever and always—as the Impossible Dream season. They won their first pennant in 21 years in the culmination of baseball’s best-ever pennant race, which was finally settled when the radio told the tale and the champagne was uncorked: the Tigers had lost, and no playoff game was necessary. They would finish the season one game behind the Sox with Minnesota. With 44 homers, 121 RBI, and a .326 batting average, Carl Yastrzemski won the Triple Crown (no one has done it since, or even come close). He capped the year with a 7 for 8 hitting performance in the last two games. That season was the launching pad for all of the team’s success since then. After eight straight losing campaigns, the Red Sox would go on to have 16 straight winning seasons and establish the base of Red Sox Nation.