Fenway Park (15 page)

Authors: John Powers

He hired Stanley “Bucky” Harris, the “Boy Manager” who’d directed the once-woeful Senators to two pennants and a Series championship before he’d turned 30 and who’d just been cut loose by Detroit. Harris inherited an expensive new lineup for 1934 and an even more expensive playpen that Yawkey had to renovate twice after a January fire turned much of his new handiwork into cinders. Though the construction costs were soaring for what would be the city’s biggest private building project of the decade, Yawkey had cash to burn. “Hang the money,” he declared in early January. “What is the use of having money unless you do something with it?”

More than 30,000 fans turned up for the home opener against defending champion Washington and marveled at the Fenway improvements, which included an electronic scoreboard at the bottom of the left-field wall that was a baseball version of a traffic signal with its red and green lights. “They did everything in christening the new Fenway but crack a bottle of champagne over the prow of home plate,” John Barry remarked in the

Globe

.

When the Yankees came to town five days later, nearly 45,000 people jammed into the park and another 10,000 were turned away. As attendance for the season ballooned past 600,000, the Sox ascended to the first division for the first time since Babe Ruth’s departure and broke even with a 76-76 record. Had Lefty Grove not been sabotaged by abscessed teeth and a sore shoulder, they might have finished even higher than fourth place. “We were all set to shoot for third place,” Harris said in April, “and I believe we could have made it until this terrible thing happened.”

Park improvements in the early 1930s included a new dugout for the visiting team.

DAVE EGAN: “THE COLONEL” HELD COURT

In 1977,

Boston Globe

columnist Mike Barnicle wrote about Dave Egan, who covered the Red Sox for the

Globe

and later, for the

Boston Record

. Barnicle told the story of a boy who spotted Egan sitting alone at the old Hotel Kenmore bar.

“Excuse me,” the boy stuttered as he approached. “Are you Dave Egan?”

“I am,” Egan said, looking older and smaller than the boy ever imagined.

“I write you letters all the time. I think you’re wrong a lot,” the boy said, his knees shaking.

“I probably am, kid,” Egan replied. “But I never look back. It takes too much time.”

“It must be great, knowing all those ballplayers and everything like you do,” the boy said.

“Listen, kid,” Egan replied. “They’re lucky to know me.”

Egan, who apparently awarded himself the “Colonel” nickname, was never shy about displaying his ego in print. “[He] would put these awful things in the paper—these awful, outrageous, untrue, fascinating, interesting things,” wrote Barnicle. “Ted Williams was always ‘T. W’ms Esq.’ in one of The Colonel’s pieces. . . . Egan was so irritating that he probably sold 100,000 copies a day on his own.”

Ray Flynn, who would go on to become the mayor of Boston, told Leigh Montville, “I used to sell the Record at the ballpark when I was a kid. Ted Williams was my idol. Whenever The Colonel would write something bad about him, I’d go through all my papers and rip out the page that had The Colonel’s column on it. It was my own little tribute to my hero. I swear on my mother I did this.”

When Egan died in 1958 at age 57, Boston’s archbishop, Richard J. Cushing, lauded him as a man “blessed with a great natural talent. . . . While all the people who read his columns didn’t agree with him, they all appreciated him.”

An example of Egan’s prose was his story about the 1932 home opener at Fenway Park, in which Senators left fielder Henry “Heinie” Manush hit a game-winning, three-run homer with two outs in the ninth inning. The piece began: “Perhaps he is not a varlet. Probably he is not even a viper. But Henry E. Manush of the Washington Senators (born in Tuscumbia, Ala., in 1901, by actual count) was the ruination of the Red Sox yesterday afternoon at Fenway Park.

“The ninth inning froze the chilled crowd that sat through the harsh April day. Jack Russell, who threw them for the Red Sox, had staggered through the game quite well, viewing everything in a large and statesmanlike manner, and entered the last inning with a comfortable lead of three runs. But woeful events transpired, and Manush lashed out his home run, and so the Red Sox lost their second successive game by the margin of one run.

“The Chowder and Marching Organization, headed by the Messrs Bob Quinn, Nick Altrock and Al Schacht, and accompanied by Jimmy Coughlin’s 10

th

Infantry Band plus the athletes, gave a swank parade to the flagpole in center field, where Walter Johnson and “Shano” Collins raised the American flag on high.

“Hon. James M. Curley, Mayor of Boston, emulated Jimmy Walker, Mayor of New York, by arriving on the scene at a late hour, and it is to his discredit that he sneaked away before the blazing finish of the game. I suppose it proves that Hizzoner has no end of brains, for it was an Antarctic afternoon, more suitable for football than baseball.

“But let us get around to the ball game, if you please . . .”

In an October 9, 1976, op-ed story, the

Globe

’s Robert Taylor lamented departed writers, including the late Egan: “The Colonel was the maestro of sprung syntax (“And this I tell you . . .”), whose prose made you feel that you were in the back room of a dingy smoke shop, with the cops pounding on the door and the proprietor swallowing the betting slips.”

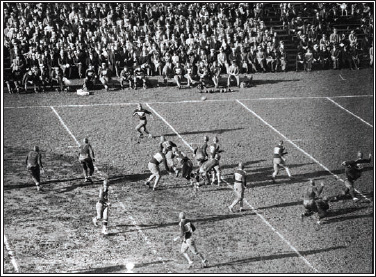

A TASTE FOR PIGSKIN

Boston Redskins vs. New York Giants, 1933.

When the Newark Tornadoes of the National Football League folded after the 1930 season, the franchise was sold back to the NFL. The players and the berth in the league would eventually go to George Preston Marshall, who secured a league charter to place a team in Boston.

In an April 21, 1932,

Globe

story headlined “Pro Football Plans for Boston Outlined,” Marshall noted that pro football attendance had risen 35 percent in the previous season. The story went on to say, “A canvass of this section where football is thoroughly understood has led the promoters to place a club in Boston.” Though they may have understood the game, Boston sports fans were slow to embrace it.

Marshall named his team after the baseball Braves, with whom it shared Braves Field in its first season. The football Braves made their debut on October 2, 1932, losing at home to the Brooklyn Dodgers. A week later they secured their first win, 14-6, over the New York Giants. They completed their first season with a 4-4-2 record under head coach Lud Wray, but the games were so poorly attended that Marshall moved his team to Fenway Park in 1933.

Since his team was no longer playing in the same park as the Braves, Marshall changed the nickname to the Redskins—reportedly to honor their new head coach, William “Lone Star” Dietz, a Native American. The new nickname also allowed Marshall to continue to use the uniforms from the previous season.

In their first two years at Fenway, the Boston Redskins continued to play .500 football, finishing with records of 5-5-2 and 6-6. In 1935, the Redskins suffered from a punchless offense, scoring just 23 points during a seven-game losing streak en route to a 2-8-1 record.

The 1936 season—their final one in Boston—would also prove to be the Redskins’ most successful on the field in Massachusetts. They won their final three games to capture the NFL’s Eastern Division with a 7-5 record, outscoring their opponents, 74-6, in those three games. The Redskins featured a pair of future Hall of Fame players in running back Cliff Battles and offensive tackle Turk Edwards. But when they routed the Pittsburgh Pirates, 30-0, in their next-to-last game of the season, only 4,813 fans showed up at Fenway Park.

Marshall was so outraged by the meager turnout that he gave up the home field for the NFL championship game, choosing to face the Green Bay Packers at New York’s Polo Grounds. The Redskins lost, 21-6, and citing the lack of fan support in Boston, Marshall moved the club to Washington, D.C.

On December 6, 1936, the

Globe

’s Paul V. Craigue was at the NFL title game in New York, and he wrote of the change of venue, “Nobody could offer a satisfactory excuse for the minor-league move by a ‘major-league’ club.” Marshall claimed that he moved the game for the players’ sake. “They get 60 percent of the playoff gate, with 20 percent going to the league and 10 percent to each club. We’ll get a much bigger gate here than we would in Boston.” Marshall went on to say, “We don’t owe Boston much after the shabby treatment we’ve received. Imagine losing $20,000 with a championship team.”

Craigue defended the fans’ indifference, noting that the Redskins “gave their worst exhibition of the season before their largest crowd and lost three of their five home games before starting their title surge against the lowly Brooklyn Dodgers. Maybe, after all, Boston would turn out for a real attraction.”

He went on to ask, “Can you imagine the Red Sox winning the American League pennant and shifting their World Series games to Yankee Stadium in the interest of the gate?”

The franchise’s move proved fortuitous for Marshall. The Redskins drafted a star college quarterback named Sammy Baugh before their first season in D.C., where they drew nearly 25,000 fans for their first home game. Baugh guided them to an 8-3 regular-season record in his rookie year and then threw three touchdowns to lead the Redskins over the Chicago Bears in the championship game. Baugh went on to a Hall of Fame career, and the Redskins had nine straight winning seasons in D.C. en route to becoming one of the NFL’s most successful franchises.

Eight years after the Redskins’ departure, another NFL club made an unsuccessful foray into Fenway Park. Ted Collins, a former recording executive who had become the manager and partner of popular singer Kate Smith, wanted to put a team in New York City and call it the Yanks. He was forced to settle for Boston, though he kept the Yanks nickname. Perhaps that name choice for a Boston team doomed it from the start.

The Yanks never had a winning season in Boston, going 2-8, 3-6-1, 2-8-1, 4-7-1, and 3-9. Collins was given permission to move the franchise to New York in 1949, though for some reason, he renamed his team the Bulldogs. They played three seasons in New York (the latter two, again, as the Yanks), before moving to Texas where they played as the Dallas Texans for one season. The franchise was sold and became the Baltimore (now Indianapolis) Colts in 1953.

The other early Boston NFL franchise was the Boston Bulldogs, who played just one season (1929) when the former Pottsville (Pa.) Maroons were sold to a New England-based partnership that included George Kenneally, a standout player for the Maroons. They played their home games at Braves Field, chalked up a 4-4 record and folded after one season in Boston.