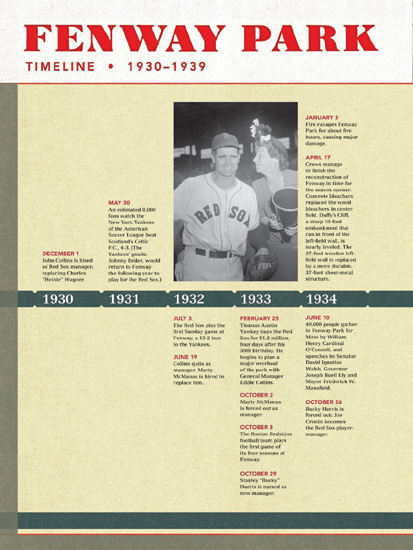

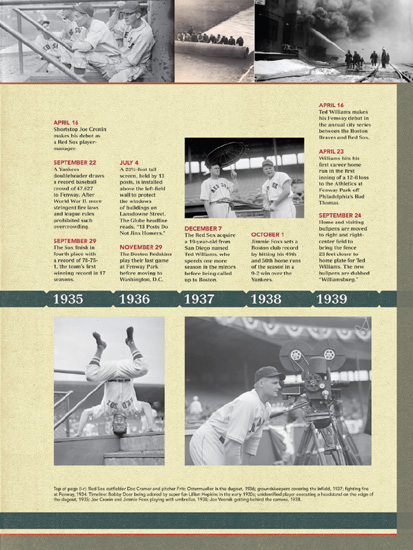

Fenway Park (18 page)

Authors: John Powers

“Who cares if the Yankees win the pennant after this?” crowed Cronin’s wife, Millie, after Foxx had circled the bases with what the

Globe

’s Moore called “a grin as wide as the Sahara Desert.” By then New York had already run away with the league en route to a third straight world championship. But Boston’s second-place showing was its best since Ruth had departed.

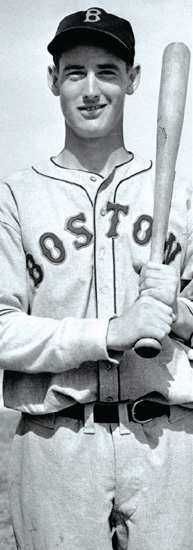

Another potential Ruth arrived in 1939 in the form of Ted Williams, a goofy and gangly 20-year-old out of San Diego who was so skinny that he eventually was dubbed the Splendid Splinter. He’d arrived at spring training a year earlier full of braggadocio that was deemed the prerogative of a veteran like Foxx, whose slugging credentials were beyond dispute. “Foxx ought to see me hit,” he proclaimed.

Doc Cramer, Joe Vosmik, and Ben Chapman, who’d had the outfield jobs locked up, mocked Williams mercilessly. “Tell them I’ll be back,” Williams told clubhouse man Johnny Orlando as he was shipped up to Minneapolis for seasoning, “and I’m going to wind up making more money in this game than all three of them put together.”

There was no keeping Williams down the following season, although Cronin, who’d originally dubbed him, “Meathead,” was quick to sit the rookie when he threw a ball over the grandstand roof in Atlanta after misjudging an outfield fly in an exhibition game. “I’ll continue to crack down on him until all the ‘bush league’ is out of him and he begins to act like a major leaguer,” the skipper vowed.

Raising the backstop—an April ritual.

There was nothing bush about his bat, though. “If he puts it there again, I’m riding it out,” Williams promised after Red Ruffing had struck him out twice on Opening Day in New York, and then hammered a ball more than 400 feet that just missed going over the fence. In his third game at Fenway, Williams went 4 for 4 and hit his first homer. In Detroit, he launched the two longest homers ever hit at Briggs Stadium. “This kid can hit a baseball as far and as hard as any ballplayer that ever lived,” a rival told sportswriter Grantland Rice. “And I’m not even barring the Babe.”

“The Kid” was Ruthian in both his power and his personality, which was unapologetically adolescent, marked by what Moore described as “his constant boyish chatter, seldom possessing any meaning” and his “screwball acts.” But his rookie numbers were irrefutably adult—.327 with 31 homers, 145 RBI, and 107 walks from pitchers reluctant to see their offerings sailing into the seats.

Even before Williams earned the nickname “Thumping Theodore,” his colleagues had been optimistic about dethroning the Yankees, who’d been picked by their manager Joe McCarthy to win a fourth straight crown. “Perhaps the Fates will cross him up on the prediction,” Cronin said. As always, though, it was a futile and frustrating chase that ended with a fiasco at the Fens on Labor Day weekend.

After winning the opener of the Sunday doubleheader by squeaking by the Yankees, 12-11, the Sox hoped to salvage the nightcap by stalling as the clock approached the 6:30 p.m. curfew with New York leading, 7-5, in the eighth. If the game couldn’t be completed by then the score would revert to 5-5 (the score at the end of the seventh inning), so Cronin ordered an intentional walk to Babe Dahlgren to load the bases. But the Yankees countered by playing hurry-up, as George Selkirk and Joe Gordon trotted home and let themselves be put out.

After the fans littered the field with soda bottles, straw hats, and rubbish, umpire Cal Hubbard called Fenway’s first forfeit and awarded a 9-0 victory to the visitors, a decision that later was rescinded by the league president, Will Harridge, who ordered a replay that was scrubbed by rainouts. Not that it mattered. Boston already was hopelessly in arrears and ended up 17 games behind.

Ted Williams at spring training in March 1938. The “Splendid Splinter” made his Red Sox debut in 1939, hitting .327 with 31 home runs and 145 RBIs.

HATS OFF TO ARTHUR D’ANGELO

BY STAN GROSSFELD

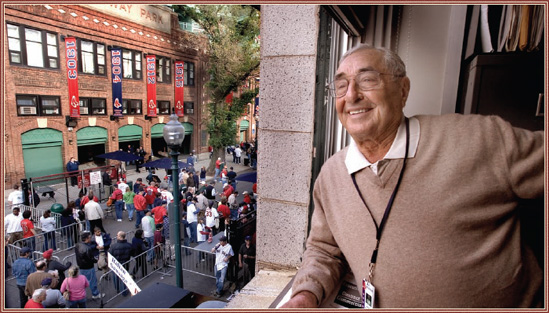

In blazing sunshine directly across the street from Fenway Park in 2006, Arthur D’Angelo, 79, was slowly and methodically pressure-washing the stale beer off the sidewalk in front of his souvenir store. By the time he finished, one side of Yawkey Way was clean enough to eat an

El Tiante

Cuban sandwich off it.

Inside the megastore, D’Angelo’s 65-person staff was enjoying the air conditioning. But D’Angelo, a short man with a sweet smile, didn’t want to delegate the cleaning chore.

Arthur and his twin brother, Henry, arrived in Boston’s North End from Italy with their family in 1938, fleeing the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini. “I was 14 when we came to Boston,” he said. “I couldn’t speak a word of English.”

The brothers started hawking newspapers, the

Daily Record

and the

Boston American

. The two eventually wandered from the North End to Dorchester to Fenway Park.

“We saw these crowds,” D’Angelo said. “We didn’t know what baseball was. We snuck into the ballpark. The game started at 2 p.m. and we thought, ‘What are these idiots doing with a baseball bat?’ But then it caught on and we loved the game. Why not capitalize on it?” They did, in a big way.

D’Angelo said that the Souvenir Store, run by Twins Enterprises, Inc., is the largest of its kind. Most locals refer to it as “Twins” even though Arthur D’Angelo’s twin brother Henry died in 1987.

“We sell more caps than anybody in the world,” said D’Angelo, who operates Twins Enterprises with his four sons. “We make them for all the major-league teams. We also have licensing for 200 colleges.”

After a stint in the Army, D’Angelo was discharged in 1946 and returned to Fenway, hawking pennants. Interest in the team was high, as the 1946 Sox won their first American League pennant since 1918 and played to a record 1.4 million fans.

“Ted was back from the service,” D’Angelo said. “They had Dave Ferriss, Bobby Doerr, Dom DiMaggio, and Johnny Pesky. Pennants were 25 cents. We had buttons with the players’ pictures on them. We used to buy ‘em for 12 cents and sell them for a quarter. You didn’t need a license back then.”

The D’Angelo brothers rented space outside Fenway until 1965, when they borrowed $100,000 and bought the building on Jersey Street (now Yawkey Way) that still houses the Souvenir Store. It almost folded.

In 1965, the Sox suffered through a 100-loss season, and the next season they drew just over 800,000 fans to Fenway to watch them finish ninth. “Nobody wants to remember a loser,” said D’Angelo.

But then came the Impossible Dream team of 1967. “My favorite team was 1967,” said D’Angelo. “The Sox won the pennant, then lost the World Series in the last game. Besides Yaz, there were no real standout players, but they all charged into it.”

Arthur D’Angelo surveyed the scene on Yawkey Way from his office.