Fenway Park (20 page)

Authors: John Powers

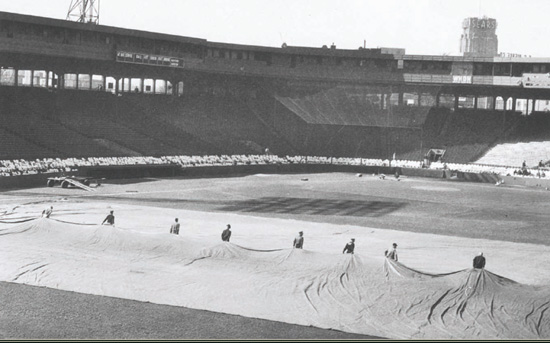

Daily life for grounds crews in the ‘40s included pulling tarps and pushing lawn mowers.

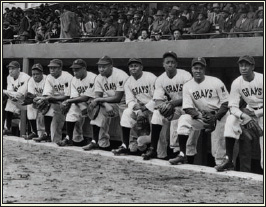

HOMESTEAD GRAYS COME TO TOWN

The Homestead Grays, the two-time defending champions of the Negro League who featured Hall of Famers such as Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard, defeated the Fore River Shipyard team of the New England Industrial League, 1-0, in a game played at Fenway Park on May 26, 1944.

The Grays, who were based in Homestead, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, played many of their games at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh while also using Washington’s Griffith Stadium as a second “home” park. The team also barnstormed and often played two or three games a day against local amateur and professional teams.

The Boston

Globe

had published a one-paragraph story under the headline: “Negro Home Run King at Fenway Tonight.” Second only to the legendary Satchel Paige among Negro League players in terms of fame and popularity, Gibson was generally considered to be the greatest hitter in the history of black baseball and was nicknamed the “Black Babe Ruth.”

The story also reported, “A United States Marine band will furnish music. Jack Burns, Skinny Graham and Charlie Bird will be in the Fore River lineup.” The game account the next day showed the Grays out-hitting Fore River, 11-5, on their way to a 1-0 win. Some 3,000 fans attended the game.

Gibson reportedly won nine home-run titles and four batting championships during a 17-year career that ended in 1946. Paige called him “the greatest hitter who ever lived.” Hall of Fame pitcher Carl Hubbell noted, “Any team in the big leagues could use him right now.”

While Gibson certainly could have helped any major-league team that elected to sign him, the unwritten rules of baseball kept him out of the majors his entire career. Frustration over his lack of opportunity, various illnesses, and despondency over the death of his wife in childbirth caused Gibson to die of a stroke at the age of 35 on January 20, 1947, just three months before Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier.

Two days after the Grays played at Fenway, the ballpark hosted a military memorial Mass that was attended by an estimated 6,000 people. In his sermon, the Reverend John S. Sexton, an American Legion chaplain, spoke out against racial and religious hatred, saying, “Jim Crow-ism and anti-Semitism are un-American, because in the first instance they are anti-God. Let’s put America ahead of our own little cheap individual, and group interests.”

On June 3, 1947, the

Globe’s

Hy Hurwitz wrote a story that said the Red Sox were considering signing Negro League star Sam Jethroe. The story noted that Jethroe, who was playing for the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American Baseball League, was considered the best hitter in the Negro Leagues since Gibson. Jethroe had led the league in both batting average and stolen bases as the Buckeyes won the Negro League title in 1945, beating the Grays in the championship series.

Had they signed Jethroe, as they were reportedly considering, the Red Sox would have been the only Major League Baseball team other than the Brooklyn Dodgers, who had signed Jackie Robinson in 1945, with a black player on its roster. Jethroe ended up signing with the crosstown Boston Braves, and he would go on to be named the National League’s Rookie of the Year in 1950. It would be more than a decade before the Red Sox promoted Pumpsie Green to their big-league club, making the Sox the final MLB team to integrate its roster.

The Williams melodrama went until the last day of the season. His average was .406 after his final home game against the Yankees, which he punctuated with a home run. Going into the concluding doubleheader at Philadelphia, it had dipped to .3995. Though Cronin offered to let him sit out the final two games so that his average would be rounded up to .400, Williams was adamant about playing

both

games. “A batting record is no good unless it’s made in all games of the season,” he declared. Then he proceeded to go 6 for 8 with a homer against the last-place Athletics and finish the season at .406. “Ain’t I the best goddamn hitter you ever saw?” Williams proclaimed in the clubhouse.

Joe DiMaggio, who strung together a record 56-game hitting streak as the Yankees breezed to the pennant, might have been the Most Valuable Player, but even he wouldn’t challenge the Kid’s primacy at the plate. Williams had a more than reasonable reprise in 1942, leading the league in batting average (.356), runs (141), RBI (137), and homers (36). But with the country at war after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, there was some dispute as to whether he should be playing at all.

Bob Feller, Hank Greenberg, and Sox teammate Mickey Harris already had been called to duty and Williams’s draft board in Minneapolis had reclassified him 1A in January. But since he was supporting his mother, Williams was switched to 3A on appeal and turned up at training camp. “If Uncle Sam says fight, he’ll fight,” Cronin said in February. “Since he has said play ball, Ted has a right to play.”

But only for one more year, Williams vowed at the end of March. “No matter what happens during the coming season, I’m going to enlist when it’s over,” he said. Williams began it auspiciously, lofting a three-run homer into the bleachers in his first at-bat in the Opening Day victory over the Athletics at Fenway. But despite the emergence of a brace of promising rookies (right-hander Tex Hughson and shortstop Johnny Pesky), the Sox couldn’t catch the Yankees and finished nine games behind their rivals despite winning 93 games, their highest season total since 1915.

The season finale in the Fens, a symbolic 7-6 victory over New York, was telling. The story of the day was that the fans donated more than 46,000 pounds of scrap metal to the war effort. By 1943, the Sox would be donating a third of their lineup to the cause.

Williams and Pesky had enlisted with the Navy Air Corps and DiMaggio with the Coast Guard. So Cronin, who’d been easing out of his role as player-manager, pressed himself back into service at 36. The 1943 season figured to be a lost cause anyway after Boston dropped 10 of its first 14 games (seven of them to the Yankees) and sank into the cellar after the first week in May. So the skipper chose Bunker Hill Day, which commemorated a gallant but ultimately losing battle by American rebels against the British in the Revolutionary War, to make a bit of history himself.

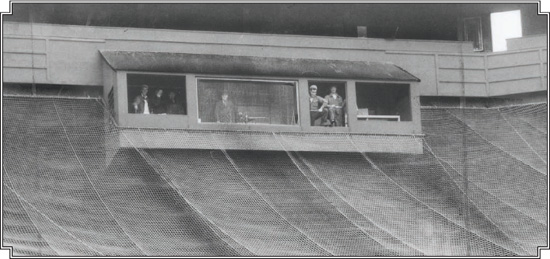

The decade’s renovations included a television and radio coop, perched atop the screen behind home plate.

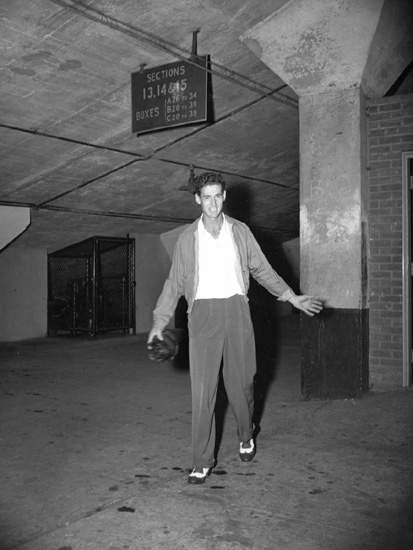

His attitude wasn’t always so sunny, but Ted Williams smiled for the camera when he left the Fenway Park locker room in July 1942.

“I guess the old man showed them something today,” Cronin crowed after he’d pinch-hit home runs in both ends of a doubleheader against the Athletics at Fenway, becoming the first major-league player to manage the feat. By the end of the season he’d hit .429 with five homers coming off the bench. But there was no way to salvage a lost campaign. The Sox ended up in seventh place—29 games behind New York—for their worst finish in a decade as attendance dwindled to its lowest level (358,275) since the Depression.

Nothing was close to normal during the war. Had it been, the Browns never would have won their only pennant in 1944, displacing the depleted Yankees with a “collection of misfits, 4Fs, brawlers and drunks,” as they were described in

The Boys Who Were Left Behind

, by John Heidenry and Brett Topel. Still, Boston managed to stay in the pennant race until Labor Day, even after military enlistment took catcher Hal Wagner and Doerr, who’d been leading the league in batting in late August, and Hughson, who’d won 18 games.

Their departures, plus a killer schedule that put the Sox on the road for their final 17 games, finished them off, as the front office didn’t bother taking World Series requests. The club lost 10 in a row and finished in fourth place, a dozen games astern. “Maybe it’s just as well,” mused a

Globe

editorial, “because local fans are so badly out of practice they wouldn’t know what to do with a championship.”

By 1945, Uncle Sam had spirited away virtually all of the former regulars and the Sox were happy to consider anyone who might be capable of playing 154 games without tripping over himself. So the day before the season opener in New York, the club ran a Fenway tryout for three black players—Jackie Robinson, Sam Jethroe, and Marvin Williams—who were performing in the Negro League. Roxbury city councilor Isadore Muchnick had badgered the club to break baseball’s color line and the players suspected that the workout was perfunctory. Though scout Hugh Duffy proclaimed them “pretty good ballplayers,” the front office didn’t sign them. “Not for one minute did we believe the Boston tryout was sincere,” Robinson would remark. “We were going through the motions.”