Fenway Park (23 page)

Authors: John Powers

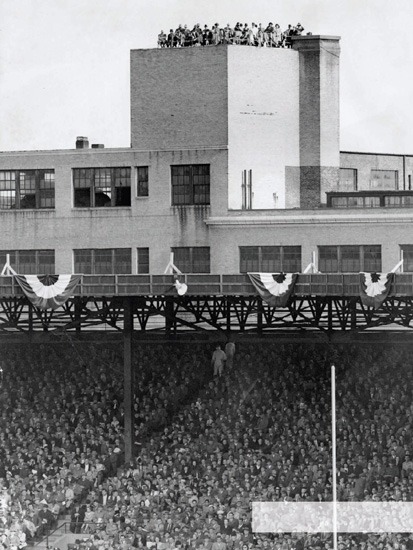

A crowd gathered on the roof of the post office building overlooking Fenway Park during the 1946 World Series.

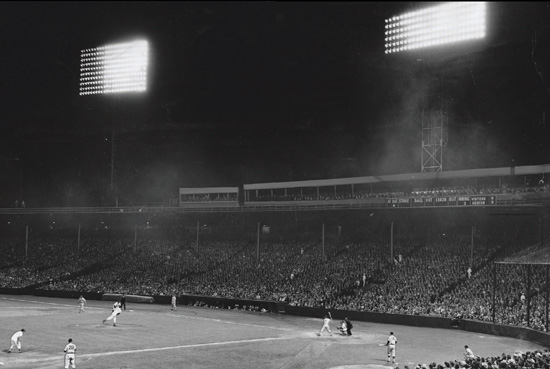

NIGHT BASEBALL DEBUTS AT FENWAY

The Red Sox played their first night home game on June 13, 1947, before 34,510 fans. And although some ominous signs were noted beforehand—it was played on Friday the 13

th

, as the opener of a 13-game home stand—it turned out well for Boston. The Globe’s Bob Holbrook reported the next day that the ball club “inaugurated night baseball at Fenway Park in a fashion pleasing to Bostonians as they tipped over the Chicago White Sox, 5-3, before a near-capacity crowd.”

The Red Sox were the third-to-last of the 16 major-league teams of the time to install lights in their home park, and owner Tom Yawkey was clearly reluctant to do so. As a preview story in the

Globe

by Hy Hurwitz noted: “No special festivities will accompany the arc-light premiere at Fenway. If not for public demand, Tom Yawkey would never have installed the giant towers over his orchard. Like Walter O. Briggs of Detroit and Phil K. Wrigley of the Chicago Cubs, Yawkey believes that baseball should be played under sunlight.” Indeed, the only ceremony accompanying the first night game was the lowering of the colors at sunset, five minutes before the 8:15 game.

The Red Sox teams of the era were the franchise’s best in nearly three decades, and in 1947 they were coming off a league championship. Certainly, they didn’t need gimmickry to fill the ballpark. As Hurwitz noted, “Yawkey is strictly in the baseball business. He doesn’t believe in fashion shows, nylon hosiery door prizes and other nonsense. As for fireworks, he hopes they will be provided by Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr, Rudy York & Co.”

The Red Sox provided little offensive firepower on opening night, as they scored all five of their runs in the fifth inning on a combination of walks, errors, and infield hits. The Sox and starting pitcher Dave Ferriss held on to win and the

Globe

story the following day noted, “You couldn’t get breathing space in the park.” It also said that the new lighting system—the brilliance of which “startled the capacity throng”—made it one of the two best-lighted stadiums in the world, equaled only by Yankee Stadium.

Yet the Sox filched Game 1 at Sportsman’s Park as York deposited one of Howie Pollet’s slow curves into the left-field seats with two out in the 10

th

inning. “I just shut my eyes and swung,” said York after the 3-2 triumph. And after Harry “The Cat” Brecheen blinded them 3-0 in Game 2, Boston’s Dave “Boo” Ferriss, who’d won 25 games, produced a dazzler of his own in the Fenway opener, which was all but decided in the first inning when York hit a three-run homer to left. “The ball which he hit struck the Cardinals right over the heart although it lodged in the fish nets many yards away,” Nason wrote in the

Globe

.

Never had the citizenry been quite so febrile about Yawkey’s paid performers. Nearly a half-million fans applied for Series tickets and hundreds of them jammed the Hotel Kenmore lobby. When standing room tickets went on sale, fans mobbed the ticket windows, nearly creating a riot.

The Cardinals, though, were unwilling to collaborate in the entertainment and they battered Boston in Game 4, matching the Series record of 20 hits set by the 1921 Giants in a 12-3 shelling. “I’d much rather lose a game 12 to 3 than 2 to 1 or 3 to 2,” shrugged Williams, whose mates

Globe

columnist Nason said had played like married men at a church picnic. “We just had our ears pinned back.”

Joe Dobson righted things in Game 5 with his “atom pitch,” an explosive curve that all but vaporized the Cardinals and staked the Sox to a 6-3 victory, sending them back to Missouri with two chances to win the championship. But Brecheen confounded Boston again in Game 6 as St. Louis knocked out Sox starter Mickey Harris early. “Well, the Cat not only skinned us again, but this time he feasted on our flesh and scratched on our bones,” Williams conceded in the

Globe

.

So for the first time since 1912, the Sox were pushed to the limit in the Series. After falling behind by two runs in the fifth inning of Game 7, Ferriss was sent to the showers. Boston drew even in the eighth when DiMaggio doubled home two men. But when he twisted an ankle rounding the bag, it proved a most costly misstep. Leon Culberson replaced him in center field. With Enos Slaughter on first base and two out, Culberson didn’t see DiMaggio motioning from the dugout for him to move more to the left.

TEN MEN OUT

For once, someone else stole the spotlight with Ted Williams at the plate.

During a game at Fenway with the Cleveland Indians on August 26, 1946, Lou Boudreau, the Indians player-manager, employed his typical Williams Shift, moving the shortstop into short right field and the third baseman to second base. The Indians’ Pat Seerey, who stood in short left field, was their only player on the left side of the diamond.

Suddenly, a midget jumped out of a box near the visitors’ dugout and walked onto the field. The man, who was later identified as Marco Songini, a vaudeville performer, picked up the glove that had been left on the field by Red Sox third baseman Mike “Pinky” Higgins and took a fielder’s stance, pounding the glove for effect. It was customary for fielders of that time to leave their gloves on the field between innings. It wasn’t until 1954 that the practice was banned.

The players, umpires, and the 28,082 fans in the park that day stared in disbelief, and then began to laugh. The laughs continued when Songini was eventually ordered off the field. He got a boost over the infield fence by Buster Mills, an Indians coach, and then climbed atop the visiting dugout and struck a fighting pose before the game continued.

The headline in the next day’s

Globe

read, “What Next at Fenway? Midget Plays Third, Indians Lose Anyway.” The Red Sox won, 5-1, and as Gerry Moore’s story noted: “Although a 10

th

man in the form of a dwarf-sized character tried to assist them by playing third base, Cleveland’s Indians couldn’t escape mathematical elimination from the American League pennant race.”

Later in the game, Cleveland pitcher Bob Lemon and shortstop Boudreau combined to pick Williams off second base. Williams was so upset with himself that he kicked his glove all the way out to left field to start the next inning. Moore noted that, “The victory, the 10

th

man, and Ted’s being picked off second seemed to satisfy the clients.”

“I believe that these temples are our secular cathedrals and they tell us as much about what we care about as anything in our environment.”

—Ken Burns, filmmaker

In August 1946, Red Sox fans’ thirst was quenched by root beer, and by their team’s pennant run.

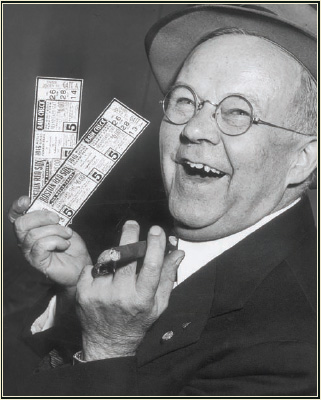

One happy Boston fan scored World Series tickets, while another wrote the local newspaper to complain that many would not be as fortunate.

SAME OLD STORY

Letter to the editor [of the

Boston Globe

], August 27, 1946:

As a Red Sox fan of the last 25 years, I should like to make a suggestion now for sale of tickets to the forthcoming World Series.

Preliminary inquiries seem to indicate that only by luck, going to the ticket scalpers, or knowing someone who knows someone will the average fan be able to get a ticket to even one game.

So-called celebrities from Hollywood and New York will occupy seats that rightly belong to Boston fans.

Wouldn’t it be fair to let Boston followers have first chance at available seats, even if it takes personal interviews with Eddie Collins and Mr. Yawkey?

—James Detrich, Brighton

FOWL PLAY

BY HAROLD KAESE

August 4, 1947—The Red Sox are really in a bad way. Not only did the Tigers claw them, 10-3, yesterday, but fans no longer bothered to ask, “What’s the matter with the Red Sox?”

Instead they wanted to know, “What’s the matter with the pigeon?”

Baseball indeed plunged to a new low at Fenway Park yesterday. The bird, identified as Parsley P. Pigeon, parked, perched, or roosted himself on the screen’s western edge about 20 feet above the backstop. He remained there somewhat longer than three hours, turning this way and that, now and then fluttering his wings, but giving no great display of worry or anguish.

The major mystery was, how could he stand it? How could he sit there enduring such a tedious game when blue skies and green fields beckoned? Obviously, he was not a homer. He was stuck, a foot or toe caught in the wire mesh. Either that or he was a Detroit pigeon and was enjoying himself heartily.

Less than 15 minutes after game’s end, a tall ladder was set up against the screen by Fenway Park’s Ladder Company No. 4. No sooner had an MSPCA agent started climbing the ladder when Parsley flew away, briskly in the direction of South Williamsburg.

Fans calling up sports departments that evening asked first, “How did the pigeon make out?” and then, “What about the Red Sox?”

According to one press box worker, Parsley was not stuck at all. “He’s just a lazy lout, that’s all. I’ve seen him before sit all afternoon on that screen, even when there wasn’t a game to watch.”

A little boy with his mother was overheard to say, “Maybe he’s going to build a nest, mama, and lay an egg.”

That probably wasn’t Parsley’s intention at all. He knew that his wouldn’t be the first egg laid at Fenway this season. Not the biggest. Nor the last.

Quoth the pigeon: “Bobby Doerr.”