Fenway Park (27 page)

Authors: John Powers

Red Sox catcher Lou Berberet took time out to mingle with the Topsfield girls’ softball team during its Fenway visit in 1958.

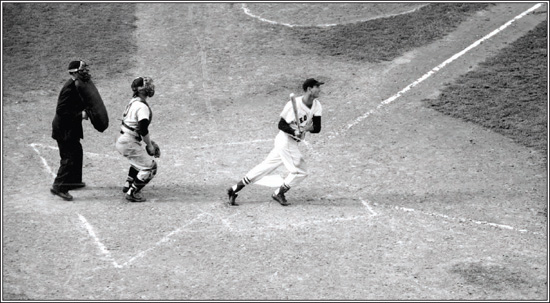

Ted Williams launched yet another Fenway home run on September 26, 1954, against the Washington Senators.

“I can’t wait to see the new park when it’s done. I want Boston to have the best. If any city needed a new park, it’s Boston. I won’t shed a tear.”

—Ted Williams, Hall of Fame Red Sox slugger

ECHOES OF “SWEET GEORGIA BROWN”

The Harlem Globetrotters made a pair of stops at Fenway Park in the mid-1950s, and the antics of the famed troupe included star dribbler Reece “Goose” Tatum punching a basketball into the crowd behind the third-base dugout, part of a faux-baseball skit performed in deference to the ballpark surroundings.

The exhibition on July 29, 1954, was part of a 12-city “Summer in America” tour organized by Globetrotters founder and promoter Abe Saperstein. The famed basketball road show was in its 27

th

season of play and fresh off a tour of South America. The hoop doubleheader drew a crowd of 13,344. Preview stories alluded to the possibility of attracting the largest basketball crowd ever in New England, but the attendance turned out to be smaller than a typical sellout crowd at Boston Garden.

Still, Francis Rosa of the

Globe

reported that fans “thrilled to the gyrations of Tatum, Leon Hillard, and Sweetwater Clifton” of the Trotters, who incidentally won the game, 61-41, over a collection of NBA players and draft picks that included future Hall of Famers Paul Arizin and Frank Ramsey and local stars Togo Palazzi and Ronnie Perry of Holy Cross. A preliminary game between the Boston Whirlwinds and the traveling House of David squad ended in a 47-46 win for the Whirlwinds, although Rosa noted that none of the winning team’s players were actually from Boston.

The doubleheader was played on the Globetrotters’ own portable court, which measured 80 feet by 50 feet and covered much of the infield, stretching from just in front of home plate almost to second base. The six-ton court was cutting-edge for the time and included a skid-proof surface developed by the U.S. Navy that would allow the Trotters to play in driving rain and other daunting conditions.

A small crowd of 3,332 watched the Globetrotters defeat the Honolulu Surfriders, 45-38, the following August at Fenway. The Trotters “clowned and capered their way through another victory,” though the team was in transition and did not feature their longtime stars Tatum or the retired Marques Haynes. Among the opponents, the best-known player was Clyde Lovellette of the Minneapolis Lakers. The evening also featured a variety of vaudeville performers before the game and at halftime.

HOSTING THE BRAVES

The Boston Braves built the 40,000-seat stadium known as Braves Field in 1915, and they were its primary tenants until the end of the 1952 season when the team left for Milwaukee. The Braves played second fiddle to the Red Sox for nearly all of their Boston years, even though their National League franchise began in 1876, a quarter-century before Boston’s American League entry was founded in 1901.

Ironically, when the “Miracle Braves” rallied to win their only World Series in 1914, they played their World Series home games at nearby Fenway Park because Braves Field, just off Commonwealth Avenue about a mile away, was under construction. It would not be ready until the following season, and in 1915 and 1916, the Braves returned the favor and allowed the Red Sox to host their own World Series games at new Braves Field, now the much larger stadium. The ballpark would host its only Braves’ postseason games in 1948, when the Braves lost the World Series in six games to the Cleveland Indians. The Indians had beaten the Sox in a one-game playoff the previous week to spoil the prospect of Boston’s only two-team “trolley” World Series.

Though the Boston Braves were marginal at best on the field (with only 11 winning seasons in 38 years at Braves Field), they had their share of historic feats. The longest major-league game in history was played at Braves Field on May 1, 1920, when they battled the Brooklyn Dodgers to a 26-inning, 1-1 tie before the game was called because of darkness. It was also the site of several Boston baseball firsts, including the Hub’s first night game and the first televised game, and the Braves also had the first black player to wear a Boston uniform: Sam Jethroe in 1950, who was named NL Rookie of the Year that season. The National League’s longest hitting streak, 37 games, was compiled by the Braves’ popular Tommy Holmes in 1945, though Pete Rose broke the record years later.

The Braves’ most successful seasons came too late—from 1945-48. Beyond that, they were a tough draw, attracting only 245,000 in 1943. It wasn’t until 1947 that the team drew a million fans in a season.

Meanwhile, local football fans had an equally fickle relationship with another Braves team. The NFL’s Boston Braves played their inaugural season (1932) at Braves Field, and then moved to Fenway Park, changing their name to the Boston Redskins. The team headed to Washington four years later because of a lack of support in Boston.

A sold-out Braves Field on Gaffney Street in Allston. Though crowds of 43,000-plus at one time packed Braves Field to watch the likes of Warren Spahn pitch—including 1.4 million in 1948—owner Lou Perini moved the team to Milwaukee in 1953 because of dwindling attendance.

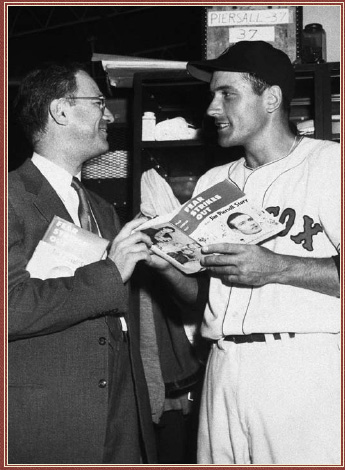

WHEN FEAR STRUCK OUT: JIMMY PIERSALL

No one who lived in Boston in the 1950s can forget Jimmy Piersall, the center fielder for the Red Sox. A swift, graceful, handsome athlete, he would be off at the crack of a bat, racing toward the wall at Fenway Park, running, straining, and then timing his leap to spear the ball at the last moment.

One day in the summer of 1953, Roger Birtwell, a

Globe

sportswriter not given to excesses, was so moved by Piersall’s fielding that he wrote: “35,000 persons sat spellbound in Cleveland Municipal Stadium yesterday and watched the greatest exhibition of outfielding in major-league history as the Red Sox beat Cleveland, 2-0, 7-5, and went into third place.”

But Piersall suffered from mental illness, reportedly bipolar disorder. In his rookie season of 1952, he was involved in fights with the Yankees’ Billy Martin, and teammates Mickey McDermott and Vern Stephens. Finally, a series of bizarre demonstrations on and off the field led to several ejections from games and culminated in a breakdown. Piersall was confined to Westborough State Hospital for electroshock therapy and psychotherapy. To everyone’s surprise, he recovered and the next year he returned to the Red Sox and became a star. Piersall was selected to the American League All-Star team in 1954 and 1956, thanks in great part to his outfield play. In 1956, he posted a league-leading 40 doubles, scored 91 runs, drove in 87, and had a .293 batting average. The following year, he hit 19 home runs and scored 103 runs. He won a Gold Glove Award in 1958, but that winter he was traded to the Cleveland Indians for first baseman Vic Wertz and outfielder Gary Geiger. Piersall earned a second Gold Glove with the Indians in 1961, also finishing third in the batting race that season with a .322 average.

In June 1963, while playing with the New York Mets, Piersall famously ran the bases while facing backward after hitting the 100

th

home run of his career.

He described his breakdown in a 1955 book,

Fear Strikes Out: The Jim Piersall Story

, which became a movie in 1957 starring Anthony Perkins and Karl Malden. (After seeing Perkins play Piersall in the film, director Alfred Hitchcock signed the actor to portray Norman Bates in

Psycho

.) Though in his autobiography Piersall blamed much of his condition on pressure from his father, he later disavowed the film, saying it distorted the facts.

One afternoon in the early 1980s,

Globe

writer Jack Thomas, who idolized Piersall as a youngster, visited him in South Carolina and accompanied him to a psychiatric ward at a Charleston hospital. When Piersall stepped off the elevator, there was a bustle among the patients, who loved Piersall, not as a ballplayer, but as a symbol of hope that perhaps they too could overcome mental illness. Piersall shook hands with the doctors, admonished two nurses for smoking, and then settled into an easy chair to chat with the children hospitalized for psychiatric care.

“Have you read my book or seen the movie about me?” he asked. “It will let you know that we all have problems. . . . I don’t have a college degree, but I’ve got a PhD in some other things. Don’t ever let anyone tell you there’s no stigma to mental illness. You’re going to have to prove yourself all over again. I know how tough it is to be alone. I’m a graduate of a mental institution.”

Suddenly, when Piersall said he was opposed to women as umpires, there was a sharp exchange between the Sox legend and a 13-year-old patient named Cynthia. It was brief, but acrimonious, and both seemed hurt. As Piersall and Thomas were leaving, Cynthia’s voice called out, “Jimmy?” He turned and walked to her quickly, knelt, and the two embraced. He kissed her cheek, and she squeezed him hard, turning her face so he wouldn’t see her tears.

“You’re a doll,” he said, “and you’re going to be OK. You’re going to make it.”

On September 17, 2010, Jimmy Piersall was inducted into the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame.