Fenway Park (28 page)

Authors: John Powers

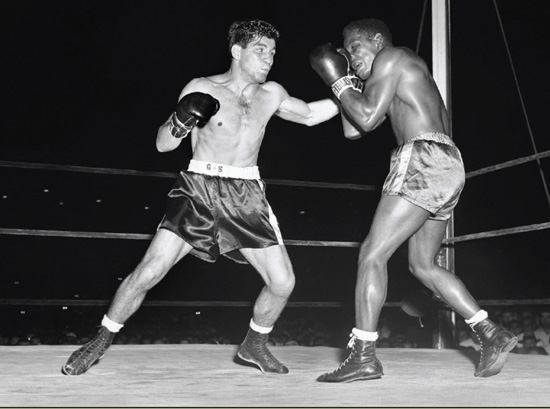

Fenway Park played host to numerous boxing matches over the years. In July 1954, Tony DeMarco, left, a welterweight from Boston’s North End, fought lightweight George Araujo of Providence. DeMarco won by a TKO in the fifth round.

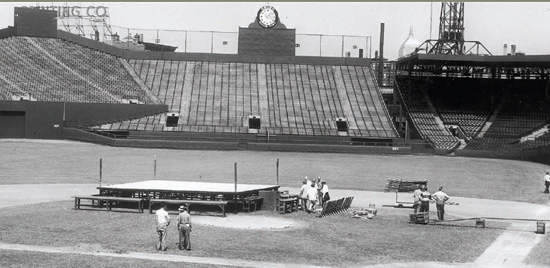

In June 1958, park personnel prepped for the arrival of television personality Ed Sullivan, who came to host the annual Mayor’s Charity Field Day.

JOHN KILEY: A THREE-SPORT STAR

Radio station WMEX was on Brookline Avenue, adjacent to Fenway Park, and John Kiley was the station’s musical director and studio organist from 1934 to 1956. When Kiley played in the studio in the early 1950s, he had a regular visitor. Unbeknownst to Kiley, that listener was Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, and Yawkey wanted to hire him.

“He was a very delightful, pleasant man,” Kiley once recalled, “and he complimented me a lot when he was around the studios, but I’d just tell him to be quiet [because Kiley was on the air]. I didn’t know who he was until he offered me the job.”

Yawkey brought Kiley on board in 1953 when he decided to add music to the Fenway experience. Kiley was also the house organist at Boston Garden from 1942 to 1984 and was proud to be the answer to the trivia question: “Who played for the Bruins, the Celtics and the Red Sox?” Kiley was quick to point out that he also played for the Boston Braves before they left town—in fact, the Braves became his first sports gig in 1941.

Kiley began taking piano lessons when he was 6 and he later quit Dorchester High School to enroll in the Boston Conservatory. He landed jobs playing for the silent movies at the old Criterion Theater in Roxbury and several other theaters, starting at age 15, before taking over at the opulent Keith Memorial Theater downtown. When

The Jazz Singer

ushered in talking pictures in 1927, Kiley found himself out of work before taking over at WMEX and the sports venues.

Kiley started at Fenway in an era when the goal was to please the owner’s wife with songs like Rodgers and Hart’s “Where or When?” (Tom and Jean Yawkey’s favorite song). He was known to pump out “White Christmas” on a scorching day, and his 20-minute pregame medley of songs might include “Embraceable You,” “Clarinet Polka,” “Misty,” and “The Way We Were.”

Kiley was not a flamboyant organist, but he did add the occasional flourish, including his spirited playing of the “Hallelujah Chorus” when Carlton Fisk hit his historic Game 6 home run in the 1975 World Series. Kiley retired in 1989 and died at age 80 in 1993.

These days show tunes on the ballpark organ are fading out in favor of loud rock on expensive sound systems. Fenway is one of a handful of ballparks that still feature organ music. “We try to do either of two things at every game: make a child fall in love with baseball, or remind an adult where, when, and why they fell in love with baseball,” Red Sox Vice President Charles Steinberg explained in 2005. “That’s why it’s essential to use the organ and pop music at Fenway.”

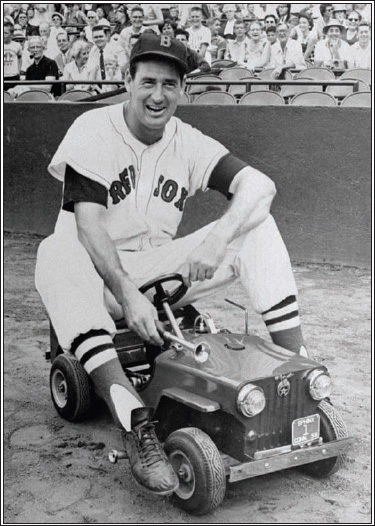

Ted Williams enjoying himself sitting in a miniature car, tooting its horn to the amusement of Fenway Park fans, August 22, 1958. The small car was one of several used by the Shriners in a pregame ceremony.

Said Yogi Berra: “He don’t look like he used to; he looks better.”

The Splinter, who ended up hitting .407 with 13 homers and 34 RBI in his abbreviated season, immediately jacked up Fenway attendance by more than 3,000 a game. Not that Boston fans had a better alternative. Once the Braves decamped for Milwaukee just before the season, the Sox literally were the only game in town.

Even though the club was in seventh place by mid-May (losing Williams with a broken collarbone on the first day of spring training didn’t help), and ended up 42 games behind the Indians in 1954, nearly a million spectators came through the Fenway turnstiles, with more than 85,000 turning up for a weekend series with the Yankees in late August that the Sox swept.

So it went for the next several years with the Sox, who remained just competitive enough to justify the price of a ticket, either staying in contention long enough or reviving late enough to keep their adherents interested. In 1955, they crept up from sixth in May to fifth in June to fourth in July and were only three games back on Labor Day before losing 12 of 14. “Our tank went dry when we needed gas,” Piersall concluded, “and we just couldn’t get a refill.”

There was always enough wall-banging to keep the customers reasonably satisfied, always a new prospect—a Harry Agganis, a Jackie Jensen, a Gene Stephens—for them to check out. And, always, there was Williams—prodigious and profane, invigorating and infuriating. He vowed that the 1954 season would be his last, saying, “You think I’m kidding, but I’m not.” But he came back by mid-May of 1955 (too late to qualify for the batting title) and hit .356 to lead the league.

His chilly relationship with “the knights of the keyboard” had turned acerbic by 1956 when he twice spat in the direction of the press box. Soon after came “The Great Expectoration,” when Williams, after being booed for muffing a two-out fly ball in the 11

th

inning against the Yankees, reeled in a blast by Yogi Berra and, on his way in to the dugout, directed several saliva shots at a record crowd of 36,350. “I’m not a bit sorry for what I did,” later declared Williams, who’d walked to produce the winning run in a 1-0 decision. “I was right and I’d spit again at the same fans who booed me today. Some of them are the worst in the world.”

Yet they were cheering him a day later after Williams, who was fined a record $5,000 by Yawkey (who never bothered collecting), smashed the game-winning homer, and then theatrically covered his mouth as he rounded the bases. “Atta boy, Ted,” one grandstand denizen applauded. “We’re all with you.” Homers always had been an instant remedy at Fenway. But there were other ways to please a crowd. Spectators were startled three weeks earlier when former ace Mel Parnell, spurned after two injury-ruined seasons, became the first Sox hurler in 33 years to pitch a no-hitter.

Parnell, who’d been knocked around by the Yankees 10 days earlier on Independence Day and hadn’t appeared since, baffled the White Sox with sinkers, facing only one man over the minimum. “That makes up for a lot of those days the past few years when things didn’t go so good,” said the 34-year-old left-hander after he’d done on July 14 what no Boston pitcher had done since Howard Ehmke in 1923—and no Sox pitcher had done at home since Ernie Shore in 1917. “Boy, it felt good to hear those people cheering me.”

“There are two places that I’ve played in my entire career that you can actually feel momentum change: Fenway Park and Yankee Stadium. You can actually feel it change.”

—Tim Wakefield, Red Sox pitcher

TED AND GLADYS

As the Globe’s Bud Collins recalled it, “Gladys Heffernan was one hardheaded woman. You can bet your Louisville Slugger on it. Sweet, congenial, grandmotherly, but—lucky for her and for Ted Williams that September Sunday afternoon in 1958—she was topped by a skull that could have gone 10 rounds with Gibraltar.”

Collins was in the Fenway press box when Williams struck out against the Washington Senators’ Bill Fischer (who would go on to become the Red Sox pitching coach in the 1980s). Williams’s temper was legendary, even at age 40, and he was so furious at striking out that, as he strode away from home plate, he took a vicious cut at the air—but the bat slipped from his hands.

There was no time for the 69-year-old Heffernan, sitting a few feet away in the first row near the Sox dugout, to react. Like a guided missile, the speeding bat beaned her. A communal gasp of horror and concern swept the park, followed by choruses of boos, as attendants rushed to the felled woman. A distraught Williams was quickly over the low wall and beside her.

As Collins told it, by the time he had run down the staircase from the press box and along an aisle to where she had been sitting, he was told by an usher that she was in the first aid room. Was she dead? The usher didn’t know.

Outside the room, Red Sox General Manager Joe Cronin greeted Collins with, “She’s fine. Nothing to worry about.”

“Fine?”

“Of course,” Cronin said with a smile. “Ted has talked to her. Apologized. She told him she knows he didn’t mean it, that it was an accident. Just a little bump.”

“But maybe a big lawsuit, Joe?” “No, no, no. There’ll be no lawsuit,” he said firmly.

Collins frowned. “This happened five minutes ago. How can you be so certain there’ll be no suit?”

“Because,” Cronin smiled again, “Gladys happens to be my housekeeper.”

Williams reportedly cried in the dugout after the accidental beaning. In his next at-bat, he doubled to drive in the second run in a 2-0 Boston win. Williams would go on to finish with a .328 average that season to win his final AL batting title.

Cronin’s daughter, Maureen, who was 13 years old at the time, recalled the incident years later. She said Heffernan spent a week in the hospital, and Williams felt awful about it. “He went to see her every day in the hospital and bought her a diamond wrist watch,” Cronin said. “She loved Ted and forgave him, but she never went to another game.”

Joe Cronin decided the family’s seats were a little too close to the action and moved them back a few rows, much to his four children’s displeasure.