Fenway Park (31 page)

Authors: John Powers

“Everything is painted green and seems in curiously sharp focus, like the inside of an old-fashioned peeping-type Easter egg.”

—John Updike, from “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu”

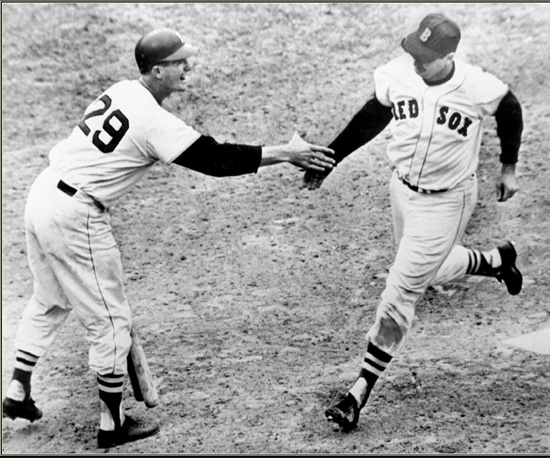

Teammate Jim Pagliaroni offered congratulations after “Teddy Ballgame” hit his 521st home run in the final at-bat of his career.

“We knew almost all the fans in the stands by name.”

—Dick Radatz, the top closer in baseball when he pitched for the woeful Red Sox teams of the early 1960s

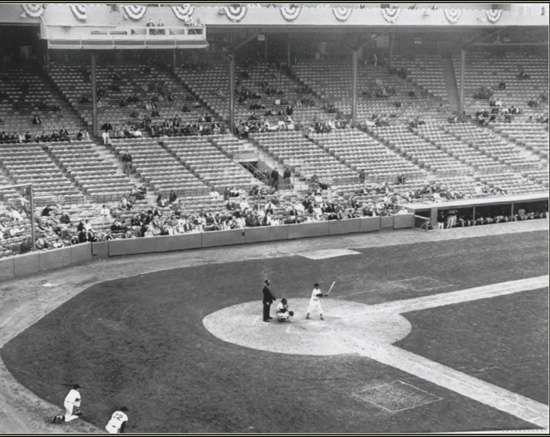

There were only 2,466 fans in the stands on April 11, 1962, when the Red Sox played the Cleveland Indians, winning the contest 4-0 on a Carroll Hardy grand slam in the 12

th

inning.

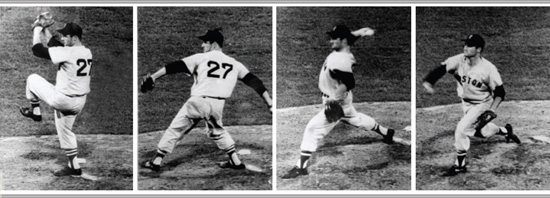

Bill Monbouquette, a native of Medford, Massachusetts, was one of the few bright spots for the Red Sox of the early 1960s. A four-time All-Star, he won 96 games over eight seasons in Boston, and he no-hit the White Sox at Comiskey Park in 1962.

A

s mediocre as most of the fifties had been for the Red Sox, the club at least had been finishing in the money at a time when that meant that most of its players wouldn’t have to spend the off-season selling tires. But by 1960, the Sox were bouncing around the bottom of the league and their owner was growing exasperated. “Want to buy a ball club?” Tom Yawkey asked broadcaster Curt Gowdy after a 12-3 home loss to the Indians. “I’ll sell it for seven million. Seven million will take it.”

It was early June and Boston already was stuck in eighth place, nearly a dozen games out of first. To shake things up one game, manager Billy Jurges switched Bobby Thomson, who’d hit the “Shot Heard ’Round The World” to win the 1951 pennant for the Giants, from the outfield to first base, where Thomson made two of his team’s four errors in the fourth inning.

“I can’t believe what I saw here tonight,” declared Yawkey, sipping bourbon in his office after the game to blot out the memory. “A guy playing first base in the major leagues with a finger glove on. A finger glove at first base. I’ll sell this club. Take it off my hands. This is the major leagues? THIS is the major leagues?”

And yet more than a million spectators came through the Fenway turnstiles that year, most of them to watch Teddy Ballgame play his final season. After his miserable 1959 campaign, by far the worst of his career, Ted Williams actually demanded that the club chop $35,000 from his $125,000 salary. Though Yawkey had suggested during the off-season that the slugger retire, Williams wanted one more .300 season and to reach 500 career home runs before he put away his bat. He easily accomplished both, batting .316 and hitting 29 homers to finish with a lifetime average of .344 and 521 career homers.

While everyone in the park knew that the midweek game against the Orioles at the end of September would be Williams’s last at Fenway, nobody but he, Yawkey, Gowdy and the clubhouse denizens knew that it would be the last of his career. Williams had a nasty cold and had asked the owner if he could skip the final series in New York. So when he deposited Jack Fisher’s fastball atop the Sox bullpen in the eighth inning, it made for a grand finale and a farewell that was completely in character.

“I thought about tipping my hat, you’re damn right I did, and for a moment I was torn,” Williams later confessed. “But by the time I got to second base I knew I couldn’t do it. It just wouldn’t have been me.” Yet Manager Mike Higgins, who’d supplanted Jurges on June 12, wasn’t going to let him get away without one last ovation. “Williams, left field,” he declared at the top of the ninth—then sent Carroll Hardy out after him once Williams had been saluted for a final time.

The club already had Williams’s successor—there was no replacement—in mind. Carl Yastrzemski, who’d grown up on a Long Island potato farm and whose father had spurned the Yankees’ lowball offer for his son, had signed a $100,000 deal while he was at Notre Dame. “We’re paying this kind of money for THIS guy?” said skeptical general manager Joe Cronin when he met his skinny bonus baby.

The Sox gave Yastrzemski the jersey No. 8 because it was nearest to his predecessor’s legendary No. 9, and assigned him the locker adjacent to Williams’s at spring training, where Williams, now a batting instructor, gave Yaz a thorough tutorial. But by midsummer, when he was stuck in a prolonged slump and haunted by Yaz-vs.-Ted comparisons, the overwhelmed rookie went to see the owner. “I feel guilty about not giving you your money’s worth,” Yastrzemski recalled telling Yawkey in his autobiography. “Could Ted come in for a day or two and take a look at me?”

‘PATRIOTS DAY’ AT FENWAY

Almost from the time it opened, Fenway Park served as a professional and collegiate gridiron for several teams. But Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey banished football from his ballpark in the late 1950s and early ’60s because he wanted to protect the grass for baseball. When Sox attendance plummeted, however, Yawkey welcomed the Boston Patriots of the American Football League to Fenway in 1963.

It’s hard to fathom today, but the Patriots operated on pretty much a shoestring budget for their first decade. The team offices were in a basement in Kenmore Square, and when it came time to draft players, reporters sat alongside as team officials flipped through the

Street & Smith

football guide to make their choices. Former Patriot star Gino Cappelletti would typically rush from training camp to anchor WBZ television sportscasts five nights a week to supplement his $7,500 salary. The Patriots played their first three seasons at Boston University’s football field (the former Braves Field) before the Red Sox offered their ballpark.

“We had played at BU and that was appreciated,” said Cappelletti. “But once we got to Fenway Park, it immediately gave us a feeling of having arrived.”

Fenway’s football configuration put one end zone on the third-base line and the other in front of the bullpens in right field. Gil Santos called the games from a makeshift booth atop the first-base grandstand, and temporary stands were erected in front of the Green Monster. Both benches were initially situated in front of the temporary stands to avoid blocking the sight-lines of fans sitting behind the first-base dugout.

“Funny thing about those side-by-side benches,” said Cappelletti. “During the games, we would get closer and closer to the other team and start eavesdropping. I remember one game when we heard [Chiefs’ head coach] Hank Stram calling for a screen pass. The next year, they put us over on the first-base side.”

A receiver/placekicker, Cappelletti booted a lot of footballs into the stands. “The bullpens in right were pretty close to the end zone so most of my extra points went over the bullpens and into the bleachers,” he recalled.

One summer, because of the uncertainty over where they would be playing, the Patriots printed tickets for three potential locations. Patrick Sullivan, the son of Patriots’ founder Billy Sullivan and the team’s former general manager, said his favorite venue was Fenway, where the Pats played for much of six seasons, until 1968.

“It was a great place to watch a football game, for precisely the same reason it is for baseball,” he said. “If you were in the temporary seats that we set up against the Green Monster—it was a big grandstand with about 5,600 seats—you were right on the action. The conversations that occurred between some of the coaches and our fans were hysterical. I was a ball boy, so I would listen in on them.”

Sullivan also remembered how players and fans would mingle on the field after games, which created a connection that doesn’t exist today.

“Romances were started, business relationships were formed, and guys got jobs during those times,” he said. “The visiting players would hang out, too, and one time I bumped into [Bills quarterback] Jack Kemp. One of the things he later told me was that it was a Patriots’ season ticket holder who convinced him to later go into politics: Tip O’Neill.” Kemp went on to a successful political career after his playing days, which included a run for the presidency in 1988.

Cappelletti and quarterback Babe Parilli were two of the team’s big stars of the time, and running back Jim Nance’s appearance on the cover of Sports Illustrated gave the Patriots national recognition in the mid-1960s. The AFL gradually gained acceptance, and later, a merger with the NFL.

“When we first got there, I don’t think many of us realized that pioneering was what we were doing,” said Cappelletti. “The original dream was survival. First, you had to survive to make the team. Then, you hoped for franchise survival. And then you hoped that the league would survive.”

“Get behind by four runs, no problem. Ahead by four in the eighth, delay the champagne. Nothing was—or is—certain, not even a pitcher sailing along. One little hit, an error maybe, can open a door to a pop-fly homer in the net. . . . That’s the magic of Fenway Park. That’s why people love it so.”

—Ned Martin, longtime Red Sox announcer

So Williams abandoned a fishing trip to give Yastrzemski a refresher course that made for a respectable debut season highlighted by 80 RBI and 11 homers. His teammates, few of whom would deign to speak to a rookie, didn’t do nearly as well, and the Sox finished in sixth place, far enough behind that they would have needed a spyglass to locate the Yankees. The highlight of the season came against the last-place Senators on a Sunday in mid-June when the Sox staged the greatest comeback in franchise history, coming from seven runs down with two out in the ninth to win the opener of their doubleheader, 13-12. They then claimed the nightcap in 13 innings, 6-5.

“You had a real bad day at the plate today,” an observer jokingly told Jim Pagliaroni, who hit the killer grand slam in the first game and the walk-off homer in the second. “You were only 2 for 11.” “Gee, that’s right,” the catcher realized. “My batting average is going to blazes.”

In a season when the Sox finished 33 games out of first place, novelties of any kind were welcome. The most notable came in the season’s finale in the Bronx when Tracy Stallard proffered the ball that Roger Maris launched for his record-breaking 61st homer of the season. “I have nothing to be ashamed of,” concluded the rookie, who pitched only one more inning for the club, but ended up as a Cooperstown footnote, albeit with an asterisk. “Maris hit 60 other homers, didn’t he?”