Fenway Park (29 page)

Authors: John Powers

“That moment, when you first lay eyes on that field—the Monster, the triangle, the scoreboard . . . the left-field grass where Ted [Williams] once roamed—it all defines to me why baseball is such a magical game.”

—Jayson Stark, ESPN analyst

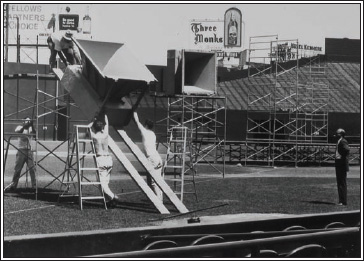

Workmen at Fenway Park strain to assemble giant speakers, part of a stereophonic system used for the Boston Jazz Festival.

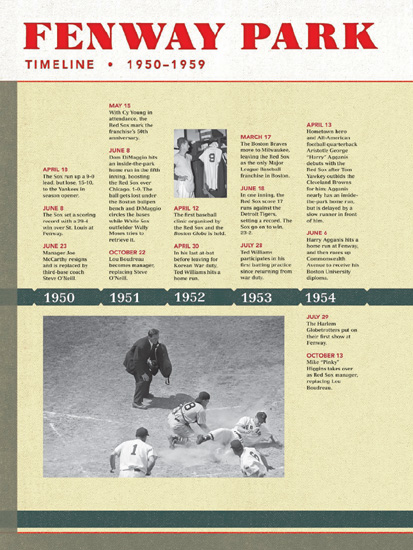

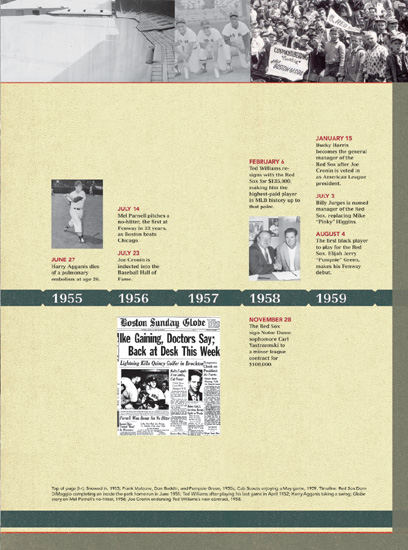

It was the last great moment for Parnell, who tore an elbow muscle and retired after the season. For nearly a decade, he’d been the mainstay of a staff that never had enough pitching, which is why Boston perennially ended up double-digits behind New York. In 1958, when Williams and teammate Pete Runnels finished 1-2 in the batting race and Jackie Jensen was Most Valuable Player, the Sox still finished 13 games out.

Had Jensen been able to play all of his games in the Fens, he might well have been a Hall of Famer. But his acute fear of flying exhausted him. When his teammates were heading for Logan Airport, Jensen often was jumping into a car and driving all night to the next city. He could handle Bob Lemon but not Rand McNally, so he quit the game a year later.

For Williams the most difficult opponent had become Father Time. He turned 41 in 1959, when a pinched nerve in his neck wrecked him for the season. The Sox sank with him and when they were in the cellar in July, Yawkey decided to ax Manager Mike “Pinky” Higgins, the former infielder who’d taken over for Lou Boudreau at the end of the 1954 season.

Yawkey dispatched General Manager Bucky Harris to Baltimore to give Pinky the pink slip. “The little one (Harris) keeps saying, ‘You gotta quit, you gotta quit,’” a barmaid told two Boston sportswriters who’d paid her to provide a report. “And the big one (Higgins) keeps telling the little one to go bleep himself.”

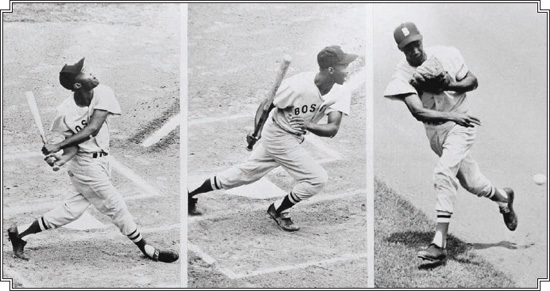

Higgins was given a scouting job and Billy Jurges, a Washington coach, was brought in to supervise the remainder of the season, which was most notable for the arrival of infielder Elijah Jerry “Pumpsie” Green and pitcher Earl Wilson, the franchise’s first two black players. Green made his Fenway debut on August 4, 1959, two weeks after he first played for the Red Sox on the road in Chicago. Ever since the club had turned up its nose at Jackie Robinson at a 1945 tryout, the Sox had shown little interest in signing African-Americans. Perhaps it was a coincidence that the owner was from South Carolina and the manager from Texas, but Boston was the last team to integrate and its all-white roster all but assured continued mediocrity.

Elijah “Pumpsie” Green made his first major league start for the Red Sox in 1959. Green, the first black player for the Sox, was honored during the team's annual Jackie Robinson Day ceremony at Fenway Park on April 18, 2009.

GREEN GIANT

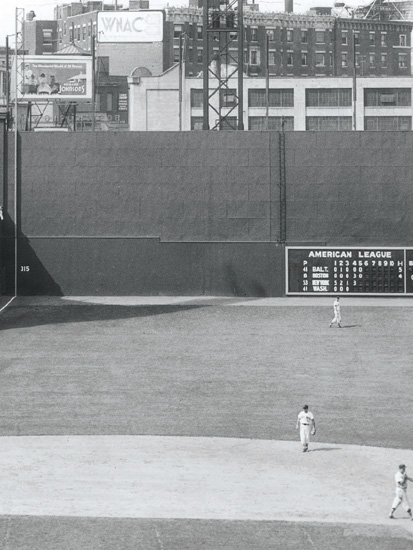

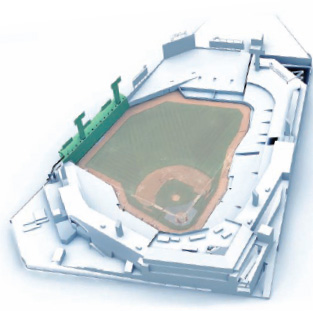

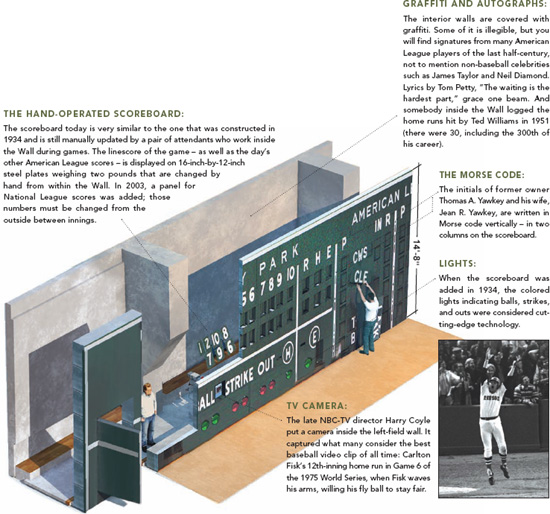

The Wall, now known affectionately as the “Green Monster,” is unquestionably the defining feature of America’s most beloved ballpark. It stands 37 feet tall and 240 feet long, and its legend has been building since 1934.

Fenway Park was created in 1912, when then-owner John I. Taylor moved the home of the Red Sox from the Huntington Avenue Grounds to an undeveloped piece of land he owned in the Fenway area. With Lansdowne Street already established, architect James McLaughlin was left with no option but to truncate the field boundaries.

The short distance to the left-field boundary from home plate was compensated by the dead-ball era of the time and the height of the wall, and though much has happened to it since then, the large, storied structure remains formidable to hitters, pitchers, and fielders today.

BELLY OF THE MONSTER

Inside the Wall, it’s scorching in the summertime and cold in the spring and fall, but scorekeepers get spectacular front-row seats and a chance to chat with outfielders, who can enter through a door that opens onto the field, during breaks in play. Manny Ramirez was particularly fond of ducking inside, sometimes barely making it back out before the game resumed. There is no permanent bathroom, although portables have been used.

HISTORY OF THE WALL

When Fenway Park was built in 1912, there was a 10-foot-tall, sloping embankment in front of a wooden wall in left field. The incline, which served as lawn seating and a picnic area for overflow crowds during the dead-ball era, as well as support for the wall itself, was tough on outfielders. However, Boston’s Duffy Lewis mastered it and the hill became known as “Duffy’s Cliff.”

When Thomas A. Yawkey bought the Red Sox in 1933, Duffy’s Cliff was scaled down, elevating the importance of the 37-foot metal fence behind it.