Fenway Park (32 page)

Authors: John Powers

It was otherwise a forgettable summer that engendered several more of the same. “There may be more broken beer bottles than broken hearts in the trail they leave behind them,” concluded

Globe

columnist Harold Kaese on the morning of the club’s Fenway finale.

Boston fans (they were not yet a Nation) derived their satisfaction from rare and wondrous moments that season. For instance, who would have predicted that the club’s first no-hitter in a half-dozen years would be pitched by an African American?

Earl Wilson, who’d grown up in Louisiana, had been signed in 1959 as Boston’s second black player after Pumpsie Green, as much for his demeanor as his ability. “Well-mannered colored boy,” said the club’s first scouting report on him. “Not too black, pleasant to talk to, well-educated, very good appearance.” Wilson had come up from the minors before the 1962 season, but he was flawless when he faced the Angels on June 26, feeding them a steady diet of fastballs. “It’s hummin’, man,” catcher Bob Tillman assured him as Wilson strung together a row of zeros and won the game, 2-0, with a homer off Bo Belinsky, who’d thrown a no-no of his own in May.

“All I can say is the Good Man was with me tonight,” proclaimed Wilson, the first black pitcher to toss a no-hitter in the American League, and the first Red Sox pitcher to hurl one since Mel Parnell in 1956—and the first right-hander to pitch a no-hitter at Fenway since Ernie Shore in 1917. Fenway’s man upstairs was suitably appreciative, as Yawkey made a rare visit to the clubhouse, gave Wilson a $500 bonus, and bumped up his salary by $1,000.

Little more than a month later, Bill Monbouquette threw another no-hitter in Chicago. It was the first time a pair of Boston pitchers had managed the feat since Dutch Leonard and George Foster both pitched no-hitters in 1916. By then, though, the season had been long lost. The Sox were entombed in eighth place, 17 games out, and Higgins, who’d morphed from caretaker to undertaker, was dismissed.

Succeeding him was Johnny Pesky, the former Sox shortstop and manager of their Triple A affiliate in Seattle. He was determined to put a stop to the “country club” culture that had become embedded over the previous decade. So during spring training in Scottsdale, Arizona he established a midnight curfew, banned swimming (because “It dulls the reflexes”) and discouraged golf. “I’m not a slave driver,” the new skipper insisted. “I’m just trying to be helpful.”

What the 1963 club needed was something close to unearthly intervention. It arrived in the form of Dick “The Monster” Radatz, a hulking closer who was coming off a percussive rookie season during which he’d led the league in relief appearances, victories, and saves and was voted “Fireman of the Year.” His repertoire consisted of one pitch—a fastball—but it was delivered from a 78-inch frame that weighed 245 pounds.

Helicopters were employed to help dry out the field in March 1967 as preparations for the season got underway. Later in the year, veteran groundskeeper Jim McCarthy used a riding mower to keep the grass in check.

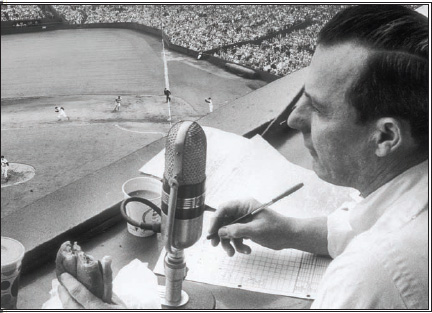

Ned Martin broadcast—on radio and TV—for 31 Red Sox seasons, partnering first with Curt Gowdy and last with Jerry Remy.

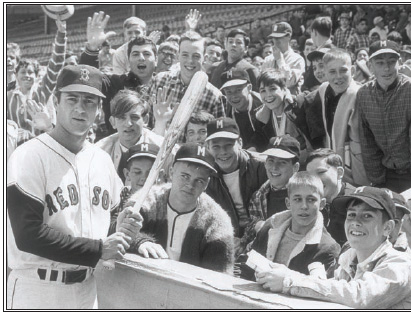

Carl Yastrzemski supplanted Ted Williams in left field in 1961 and went on to create his own Hall of Fame legacy.

During a season when victories were again hard won, Radatz’s was the only number on Pesky’s bullpen speed dial when the game hung in the balance. In June and July alone, Radatz made 30 appearances, once working six times in six days and closing out both ends of consecutive doubleheaders. In one 15-inning victory over Detroit on June 11, he pitched the final nine innings. “God bless Dick Radatz,” proclaimed Pesky. “He’s our franchise.” The

Globe

’s Kaese avowed that Radatz was to the Red Sox “what (Pablo) Casals is to music, the Prudential Tower is to Boston’s skyline.”

In the All-Star Game at Cleveland, Radatz pitched two innings and struck out five men, including future Hall of Famers Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Duke Snider. But his 15 victories and 25 saves couldn’t rescue a club that went into a summer swoon, falling from second place to seventh and finishing 28 games behind the Yankees. The Sox poster boy for the season was first baseman Dick Stuart, nicknamed “Dr. Strangeglove” for his mystifying fielding. While Stuart led the club with 42 homers and 118 RBI, he also struck out a franchise-record 144 times and made 29 errors.

Wood always had been a higher priority than leather around Fenway, so when a 19-year-old rookie from Swampscott cracked a 450-foot homer against the Indians in spring training, he immediately was plugged into the 1964 starting lineup, despite having only played a year of “A” ball. The only challenge was getting Tony Conigliaro into, and then out of, bed.

When the Sox scheduled a workout for Yankee Stadium after their season opener with New York was rained out, the rookie still was dozing at the hotel. “What a way to start a career,” he moaned. “I can hear my kids asking me some day, ‘What did you do on your first day in the big leagues, Dad?’ And I’ll say, ‘I slept.’”

Tony C., as he immediately was dubbed, was wide awake on Opening Day in the Fens though, launching the first pitch he saw from Chicago’s Joel Horlen over the left-field wall. He hit 22 more homers before the season was done, even though he missed about six weeks with various injuries, including a broken wrist and forearm. Broken curfews also were an issue, as Conigliaro was casual about bedtimes. “I am not a playboy,” he insisted after Pesky fined him for being AWOL in Cleveland.

Not that it would have set Conigliaro apart on a club that usually played as if it had been up all night. The Sox snoozed through the rest of 1964 and Pesky was dismissed two games before the end with third-base coach Billy Herman, who hadn’t managed since 1947, inheriting a club that finished eighth. They were the Dead Sox now, flatlining by May. In 1965 Boston was buried in seventh place after 14 games, en route to 100 losses with foul balls clanging off empty seats.

“When I was with Kansas City we played in Fenway one day and I was in right field, counting people in the stands,” recalled Ken Harrelson, who ended up in Boston in 1967. “There couldn’t have been more than a couple hundred.” Only 1,274 turned up on September 16 when Dave More-head, a 23-year-old right-hander who’d lost 16 games that season, pitched a no-hitter against the Indians, missing a perfect game on a full-count walk in the second inning.

THE PATRIOTS FLOP IN FIRST MEANINGFUL GAME

Gino Cappelletti peeked through his bedroom curtains and couldn’t believe his eyes. Snow? Can’t be, he said to himself.

The date was December 20, 1964, and the Patriots would be taking on the Buffalo Bills at Fenway Park in the biggest game in team history.

The game was for the AFL’s Eastern Division championship. Buffalo, led by Jack Kemp, Cookie Gilchrist, and Elbert Dubenion, came to Boston with an 11-2 record. The Patriots were 10-2-1 and had halted the Bills’ 10-0 start by beating them at Buffalo. With a win, the Patriots would capture the division and face the San Diego Chargers for the AFL title at Fenway. The Patriots sought revenge for the 51-10 whipping the Chargers had administered in San Diego a year earlier in the Patriots’ only championship game appearance.

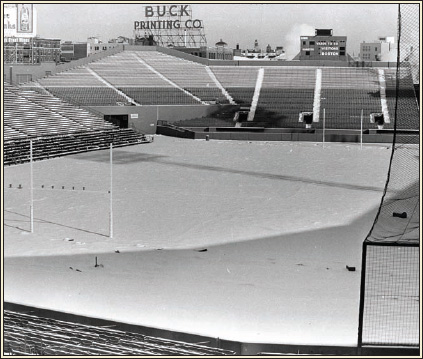

For the first time in history, a Patriots’ game not only was going to sell out Fenway Park, but it would also be the national TV game of the day. The surprise snowstorm that had hit Boston the night before meant that the game had to be delayed for 45 minutes while the grounds crew finished clearing the field. And with 38,021 fans converging on the snow-covered streets around Fenway, the entire area was in chaos.

Said Cappelletti, “I got stuck on Route 9 on the way in [from his home in Wellesley]. Thank goodness the game was delayed. The rumor in the locker room was that I got kidnapped by gamblers. No kidding. That was the story going around, and some of the guys believed it.”

Much of the crowd stood throughout the game because the seats were never cleaned. The Globe’s Bud Collins described Fenway as a glacier: “There were snowball fights and fist fights and drawing from the hip flasks.” When the game finally started, it was all Buffalo. On the first play from scrimmage, Gilchrist, a powerful fullback, leveled Patriot cornerback Chuck Shonta, who was shaken up but stayed in the game. Two plays later, Dubenion beat Shonta for a 57-yard touchdown pass.

“You could see the Bills get a lift after that,” said Cappelletti. “They also had an excellent defensive game plan.”

The Bills won, 24-14, and went on to beat the Chargers for the AFL championship. For the Patriots, it would be 21 more years before they would play in a league championship game, and it took them 37 years to win their first league title in Super Bowl XXXVI.

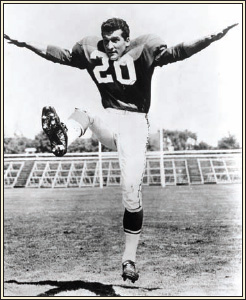

The Fenway Park gridiron was bathed in white after an unexpected storm dumped four inches of snow on December 20, 1964. The Patriots (led by Gino Cappelletti, above) played the Buffalo Bills later that day for the AFL’s Eastern Division title, falling to the eventual AFL champions, 24-14.